Table of Contents

When Music Becomes Architecture

When the final chord resonates through the concert hall, I always find myself thinking about this: some music simply passes by as melody, while other music builds magnificent structures within our hearts. Mussorgsky’s “The Great Gate of Kiev” is precisely such a piece. Though the actual gate was never constructed, it stands eternally majestic within the realm of music.

Every time I listen to this piece, I feel as though I’m standing at the threshold of time itself. A 19th-century Russian painter’s architectural design travels through a composer’s hands to reach our ears today. Can you imagine how wondrous that journey is?

A Musical Tribute to a Friend, and the Vanished Gate

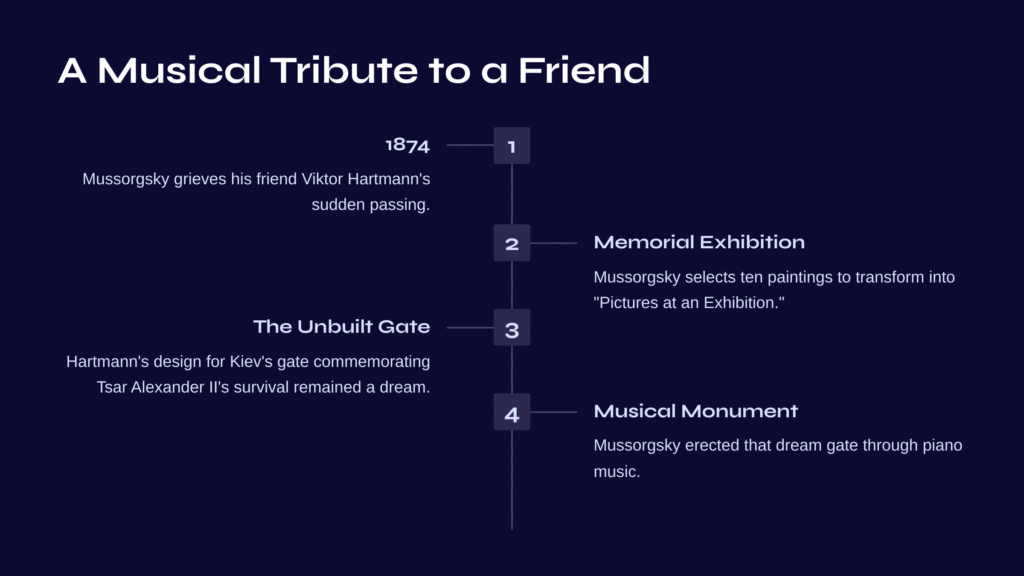

In 1874, Mussorgsky was immersed in profound grief. His close friend and painter Viktor Hartmann had suddenly passed away. From the memorial exhibition held in his mourning, Mussorgsky selected ten paintings and gave them new life as music. This became what we know as “Pictures at an Exhibition.”

The final painting was Hartmann’s most treasured work—architectural plans for a great gate in Kiev commemorating Tsar Alexander II’s miraculous survival from an assassination attempt. However, this magnificent gate was never built. It remained only as a dream on paper.

Yet Mussorgsky erected that dream gate in music. Upon the piano keyboard.

From Piano to Orchestra: Two Miracles

Initially, this piece was born as a piano solo. Majestic chords in E-flat major rise like the pillars of an enormous gate, while Russian Orthodox chant melodies flow with reverence. But the true miracle occurred in 1922.

When Maurice Ravel orchestrated this piece, “The Great Gate of Kiev” became music of an entirely different dimension. The fanfares created by brass instruments truly evoke an imperial procession, while the massive resonance of percussion fills the space like bells from a bell tower.

What’s remarkable about Ravel’s orchestration is precisely this magic of timbre. The gentle chant melodies of woodwinds, the grand harmonies of strings, and above all, the architectural sense of space created by percussion. When all these elements combine, we fall into the illusion of truly standing before that gate.

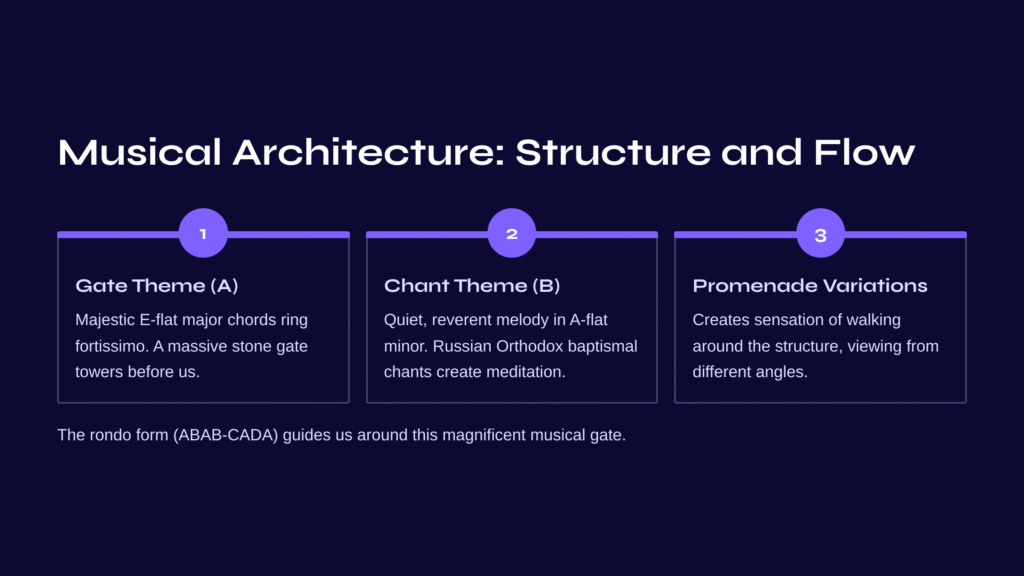

Musical Architecture: Movement Structure and Emotional Flow

The structure of this piece is truly fascinating. It’s constructed in rondo form (ABAB-CADA), as if we’re walking around that magnificent gate, viewing it from multiple angles.

The first theme (A) is the “gate” itself. When majestic chords in E-flat major ring out fortissimo, a massive stone gate towers before our eyes. The sound at this moment is truly overwhelming—as if towers reaching toward heaven are being built up note by note.

The second theme (B) belongs to a completely different world. A quiet, reverent chant melody flows in A-flat minor. Derived from Russian Orthodox baptismal chants, this represents the religious significance of the gate. In contrast to the initial majesty, this section leads our hearts into deep meditation.

The variations of the “Promenade” theme that appear intermittently create the sensation of walking around that massive structure, observing it from various angles. When the clockwork-like triplets gradually crescendo and return to the A theme, we come to realize the gate’s true grandeur.

Another Gate Built in My Heart

Every time I listen to this piece, I have a mysterious experience. From the moment the music begins until it ends, I feel as though I’m truly within some vast space. This transcends mere auditory experience.

When the timpani thunders in Ravel’s orchestral version, I actually feel the earth trembling. When brass fanfares resound, it’s as if an imperial procession is passing by, and when woodwind chants flow, something sublime wells up from deep within my heart.

But most moving of all is the final section of this piece. When the tempo gradually slows and all instruments unite as one, I experience something like time itself stopping. It’s as if standing within eternity—such sublime silence.

Little Secrets for Deeper Listening

If you wish to appreciate this piece more deeply, I recommend focusing on several key points.

First, try alternating between the piano and orchestral versions. Though it’s the same music, they offer completely different emotional experiences. In the piano version, you can feel Mussorgsky’s pure imagination; in the orchestral version, Ravel’s magic of color.

Second, listen carefully when the chant theme appears. While the music’s atmosphere completely changes in this section, this isn’t merely a contrast effect—it embodies the deep religious sentiment of the Russian people.

Third, concentrate all your attention on the ritardando (gradual slowing) of the final section. Here, the music almost stops time itself. In that moment, you’ll find yourself standing at the threshold of eternity that music creates.

A Gate Beyond Time, the End of an Eternal Journey

That magnificent gate was never built in Kiev. But thanks to Mussorgsky and Ravel, we can stand before that gate anytime. Through the time travel that is music.

The greatest emotion this piece provides lies precisely here: an unbuilt structure gained eternal life through music. And through the experience of standing before that gate, we encounter something sublime—beauty that transcends time.

Even after the music ends, its resonance continues for a while. It’s as if we’ve truly passed through some enormous gate. Won’t you embark on this musical pilgrimage? The Great Gate of Kiev awaits you.

Next Destination: Music That Opens Another Gate

Having passed through Kiev’s majestic gate, it’s time to open a different kind of portal. The first movement of Janáček’s Sinfonietta offers us fanfares in a completely different manner from Mussorgsky.

This 1926 composition, infused with the free spirit of Czechoslovakia, displays a different kind of power from Russian imperial grandeur. The brass chorus created by nine trumpets seems to fling wide the gates of a new era. If Mussorgsky’s music celebrates past glory, Janáček’s is music of hope for the future.

Both pieces begin with fanfares, yet their sensations are entirely different. While the Great Gate of Kiev sings of eternity built in stone, Janáček’s fanfare vibrates with life like flags fluttering in the wind. One is a monument; the other, a festival.