Table of Contents

Grace Concealing Deep Longing

The first note falling upon the piano keys. In that moment, I find myself witnessing both the ballrooms of 18th-century Versailles and the trenches of 20th-century battlefields simultaneously. This strange time travel I experience whenever listening to Ravel’s Menuet from “Le Tombeau de Couperin.” The mystique of past and present overlapping within a single melody.

Though barely three minutes long, this menuet contains within it two centuries of musical history. The elegant dance of the Baroque era and the wounds of World War I, French traditional beauty and modern harmony converging to create this unique splendor. Have you perhaps experienced something similar? That inexplicable emotion of encountering two entirely different eras simultaneously within one piece of music?

Memorial Art Blooming Amid War

Maurice Ravel composed “Le Tombeau de Couperin” between 1914 and 1917, when all of Europe was engulfed in the fires of war. The 42-year-old Ravel wanted desperately to serve on the front lines but could only serve as a driver due to his small stature. This frustration and his grief for friends who had fallen in battle became the starting point for this suite.

The title “Le Tombeau de Couperin” refers to François Couperin, the master of 18th-century French Baroque music. The term “Tombeau” (tomb) was a conventional expression used since the Baroque era for works commemorating respected musicians. Ravel borrowed this traditional form to honor his fallen comrades in his own modern musical language.

The Menuet, as the fifth movement of this suite, was dedicated to Ravel’s friend Jean Dreyfus. While faithfully following the traditional 3/4 time signature and ABA ternary form of Baroque minuets, it was reborn through Ravel’s characteristic delicate harmonies and sense of color.

Three Breaths, Three Landscapes

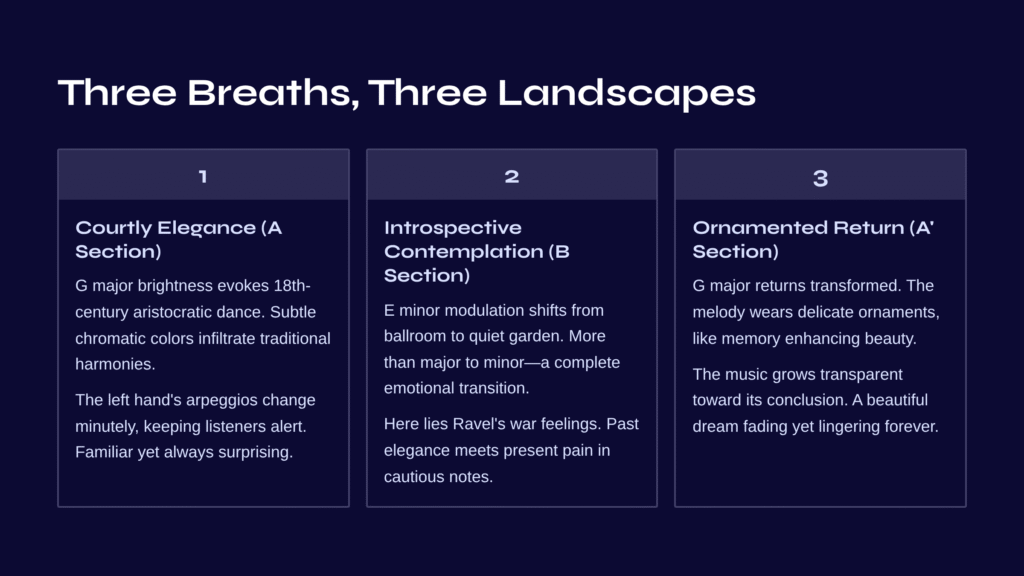

First Landscape: Courtly Elegance (A Section)

The first section begins in the bright key of G major. The main melody played by the right hand evokes the graceful dance steps of 18th-century aristocrats. Yet listening carefully, one discovers Ravel’s unique harmonies hidden throughout. Subtle chromatic colors seep into what would have been straightforward harmonic progressions in a traditional minuet, creating an effect like casting modern lighting upon an old portrait.

The left hand’s arpeggios are regular yet never monotonous. Each chord contains minute changes in nuance, keeping the listener’s ear constantly alert. This is Ravel’s genius—music that seems familiar yet always offers new discoveries.

Second Landscape: Introspective Contemplation (B Section)

With the modulation to E minor, the atmosphere changes dramatically. It feels like stepping from a brilliant ballroom into a quiet garden. Here Ravel gives a modern interpretation to the typical Baroque technique of contrast. This is not merely a shift from major to minor, but a complete transition to a different emotional world.

In this section, I always sense Ravel’s complex feelings about the war. The strange tension created by the intersection of longing for an elegant past and present pain. Each note feels cautious, as if afraid of losing something precious.

Third Landscape: Ornamented Return (A’ Section)

Returning to G major, it has become different music than before. The same melody, but adorned with more delicate ornaments, like recalling a beautiful moment from memory even more beautifully. Here Ravel reinterprets Baroque ornamental techniques in his own way, fusing past and present into one.

As the music moves toward its conclusion, it becomes increasingly transparent. Like the moment of awakening from a beautiful dream, everything gradually fades away while leaving a sense that the resonance will remain forever.

The Magic of Transforming Sorrow into Grace

Listening to this menuet, I am always amazed by Ravel’s remarkable dignity as a composer. Though this is a piece commemorating friends lost to war, there is no direct sadness or anger here. Instead, he contained all those emotions within the form of an 18th-century elegant dance, elevating them to a higher dimension of art.

Ravel reportedly said, “The dead are sad enough already.” So he honored his friends with beauty rather than tears, with grace rather than lamentation. Is this not the true attitude of an artist? The alchemist-like ability to transform personal pain into universal beauty.

There is a saying that sometimes the deepest sorrow creates the most beautiful art. Listening to Ravel’s Menuet, I come to understand the meaning of those words anew. The pain of loss seems to have made the music even more transparent and pure.

Three Points for Deeper Listening

First, compare the orchestral version with the original piano work. Ravel’s own orchestration reveals the colors of each voice part more vividly. Particularly listening to the dialogue between woodwind instruments, you can discover charms impossible to feel in the piano version. Personally, I believe both the intimacy of the piano version and the brilliance of the orchestral version each possess their own unique beauty.

Second, direct comparison with Baroque minuets is also fascinating. If you listen first to minuets by Bach or Handel, then to Ravel, you’ll be amazed at how different worlds unfold within the same form. You can directly experience the musical evolution created by a 200-year time gap.

Third, listen repeatedly. This is music that reveals new details with each hearing. At first it may sound simply graceful and beautiful, but as you continue listening, Ravel’s delicate emotions and remarkable compositional techniques hidden within begin to emerge one by one.

The Victory of Timeless Beauty

This resonance that lingers long after the piano’s final note has faded. Ravel’s Menuet transcends simple memorial music, containing deep reflections on time and loss, memory and art. In the moment when 18th-century Couperin and 20th-century Ravel meet within one piece of music, we realize that music possesses the power to transcend time.

The brutality of war, the sadness of death—all become powerless before beauty. What Ravel showed us is the ultimate victory of art. That creative force outlasts destructive force, love outlasts hatred, beauty outlasts despair. Isn’t that precisely the message this small menuet conveys to us?

Next Journey: Clara Schumann’s Romance

Having heard Ravel’s elegant memorial, how about encountering a different kind of emotion? Clara Schumann’s Romance for Piano Op. 11 No. 1 is a gem-like work containing the sincere emotions of the 19th-century Romantic era.

Clara’s unique musical world that bloomed between the temporal constraints she faced as a female composer and her complex identity as both Robert Schumann’s wife and muse. In contrast to Ravel’s restrained elegance, Clara Schumann’s Romance embraces us with pure lyricism welling up from the depths of the heart.

Clara Schumann pursued not technique for technique’s sake, but true emotional expression. In her Romance, we can simultaneously encounter the intimate atmosphere of 19th-century salons and the inner confession of a female artist.