Table of Contents

When the First Note Recognizes Your Heart

Some music reaches out to you from the very first note, as if it already knows your heart. Rachmaninoff’s Élégie in E-flat minor, Op. 3 No. 1 is precisely that kind of piece. The opening melody that falls onto the piano keys resembles the feeling of sitting alone by a window on an autumn evening, longing for something indefinable. It’s sad but not desperate, lonely yet not desolate—somewhere in that tender space between emotions.

This work, left to us by the 19-year-old Rachmaninoff in 1892, displays an emotional depth so mature it’s almost impossible to believe his age. Do you remember that subtle melancholy you might have felt in your late teens or early twenties? That complex mixture of vague yearning for the world and longing for experiences yet to come?

When I first encountered this piece, I was struck by how Rachmaninoff seemed to capture something so essentially human and timeless. Here was a teenager writing music that speaks to the deepest corners of our emotional landscape, creating something that feels both intimately personal and universally shared.

A Young Soul’s Song from Russian Soil

When Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) composed this élégie, he was a student at the Moscow Conservatory. Remarkably, this piece was dedicated to Anton Arensky, his harmony professor—it’s extraordinary that a student’s offering to his teacher could possess such profound depth and maturity.

“Élégie” is French for “elegy,” a song of lament or mourning. Yet the sorrow in this piece isn’t the kind that cries out in anguish, but rather the type that flows quietly from deep within the soul. Throughout his career, Rachmaninoff would show genius in expressing this particular shade of emotion, and this work represents the beginning of that extraordinary journey.

This élégie serves as the opening piece of the Morceaux de fantaisie (Pieces of Fantasy), Op. 3, a collection of five works. While the same set includes the famous C-sharp minor Prelude, the élégie’s unique emotional depth stands firmly on its own merits. The title “Morceaux de fantaisie” wasn’t actually Rachmaninoff’s choice—it was suggested by Arensky, reflecting the musical forms and imagery within.

The historical context adds another layer of poignancy. This was composed during the height of Russian Romanticism, when composers were finding new ways to express the Russian soul through music. Young Rachmaninoff was absorbing influences from Chopin and Liszt while developing his own distinctive voice—one that would become synonymous with Russian melancholy and passion.

A Soundscape Painted with Emotion

Listening to this piece reveals how meticulously Rachmaninoff crafted its musical architecture. The left hand sweeps across a wide range, creating a rich harmonic foundation, while the right hand sings the melody above. This structure echoes Chopin’s nocturnes, but Rachmaninoff’s unique harmonic palette creates an entirely new world of expression.

The piece begins in Moderato, maintaining a contemplative, introspective mood before the middle section marked “Più vivo” suddenly quickens the tempo and heightens the emotional intensity. It’s like throwing a stone into a still lake—the peaceful surface suddenly alive with ripples.

The climax arrives with markings of fff (fortissimo) and appassionato, unleashing explosive emotion. But here’s where Rachmaninoff’s brilliance truly shines: he cleverly subverts our expectations. Instead of resolving to the anticipated key, he leads us through unexpected harmonic progressions. This moment of tension and beauty defies simple description—it’s a masterclass in musical storytelling that speaks directly to the heart.

The piece follows a modified ABA structure, but within this framework, Rachmaninoff creates a complete emotional journey. The return to the opening material doesn’t feel like simple repetition but rather like coming home after a transformative experience.

Echoes in My Own Heart

When I first heard this piece, I experienced an odd sense of déjà vu. The melody felt familiar, as if I’d known it forever, yet simultaneously introduced me to completely new emotions. Perhaps this is because Rachmaninoff captured something so universally human in his music.

Listening to this élégie, I often find myself gazing out the window. There’s no particular reason, but something about the music’s temporal flow creates moments where past and present mysteriously overlap. It’s neither nostalgia nor sadness exactly, but something that exists in the space between those feelings.

When the unexpected harmonic shifts occur in the climactic section, I feel a bittersweet pang in my chest. It reminds me of life’s moments when we hope fervently for something, only to have events unfold in a slightly different direction. Yet rather than disappointment, there’s something mysteriously beautiful about these turns of fate.

The piece seems to understand that life’s most profound emotions often can’t be put into words. Instead, they require the language of music—the subtle interplay of harmony and melody, tension and resolution, expectation and surprise.

Secrets for Deeper Listening

First Secret: Follow the Song Without Words

This piece is essentially a “song without words.” Listen to the right-hand melody as if it were a vocalist’s line. Rachmaninoff always believed that “music must sing,” and if you pay attention to the natural breathing points and phrasing, the piece will come alive in a whole new way. Notice how the melody rises and falls like human speech, with all its emotional inflections.

Second Secret: Journey Through the Emotional Landscape

This isn’t simply a sad piece—it’s a complete emotional journey. From the opening’s quiet melancholy through the middle section’s passionate intensity to the final return to tranquility, each section offers a different emotional perspective. Don’t just listen passively; travel alongside the music as it transforms.

Third Secret: Appreciate the Art of Restraint

It’s tempting to perform or listen to this piece with excessive sentimentality, but doing so can render it cliché. Rachmaninoff achieved a delicate balance between emotional expression and artistic restraint. The key to appreciating this élégie lies in recognizing this sophisticated equilibrium—how deep feeling can be conveyed through subtle means.

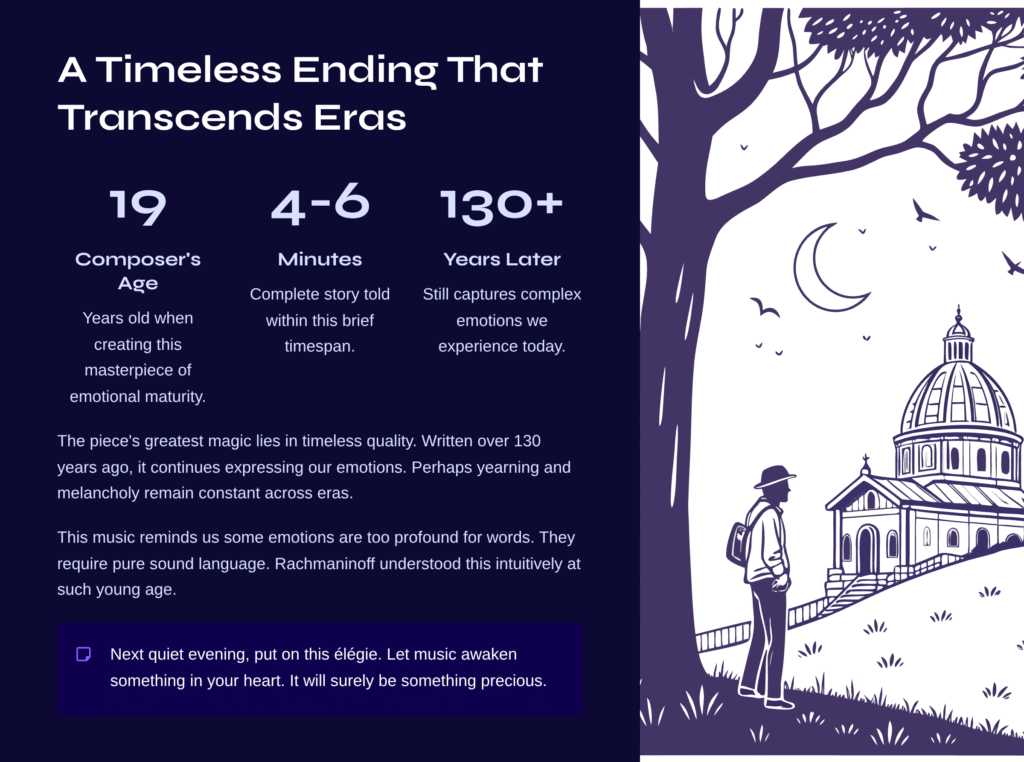

A Timeless Ending That Transcends Eras

Rachmaninoff’s Élégie accomplishes the remarkable feat of telling a complete story within just 4-6 minutes. That a 19-year-old composer could demonstrate such emotional maturity and musical sophistication seems almost miraculous.

The piece’s greatest magic lies in its timeless quality. Written over 130 years ago, it continues to capture and express the complex, subtle emotions we experience today. Perhaps the yearning and melancholy that reside deep within the human heart remain constant across all eras.

This music reminds us that some emotions are too profound for words—they require the pure language of sound, the interplay of harmony and melody, the ebb and flow of musical time. Rachmaninoff understood this intuitively, even at such a young age.

The next time a quiet evening finds you, put on this élégie. Let the music awaken something in a corner of your heart. You may not be able to describe exactly what it is, but it will surely be something precious—a reminder of the beauty that exists in life’s more contemplative moments.

The Perfect Follow-Up: Mendelssohn’s Song Without Words

If Rachmaninoff’s élégie has awakened your appreciation for “songs without words,” I highly recommend exploring Mendelssohn’s Lied ohne Worte Op. 102 No. 3.

Mendelssohn literally invented the “Songs Without Words” genre, becoming a true master of piano music that speaks to the heart without need for text. Op. 102 No. 3, in particular, features delicate and lyrical melodies that seem to engage in intimate conversation with Rachmaninoff’s élégie.

Where Rachmaninoff infused his work with Russian melancholy, Mendelssohn embodies the pure, crystalline emotion of German Romanticism. Listening to both pieces in sequence reveals how different national temperaments of 19th-century Europe found similar yet distinct ways to move our hearts.

Mendelssohn’s approach is more restrained, more Classical in its proportions, yet no less emotionally affecting. The interplay between these two pieces—one Russian, one German; one from a teenager, one from a mature composer—creates a fascinating dialogue about the universal language of musical emotion.

Both pieces remind us that sometimes the most profound communication happens without words, through the pure medium of musical sound and the emotions it can evoke in the human heart.