Table of Contents

A Secret Kept in a Parisian Workshop

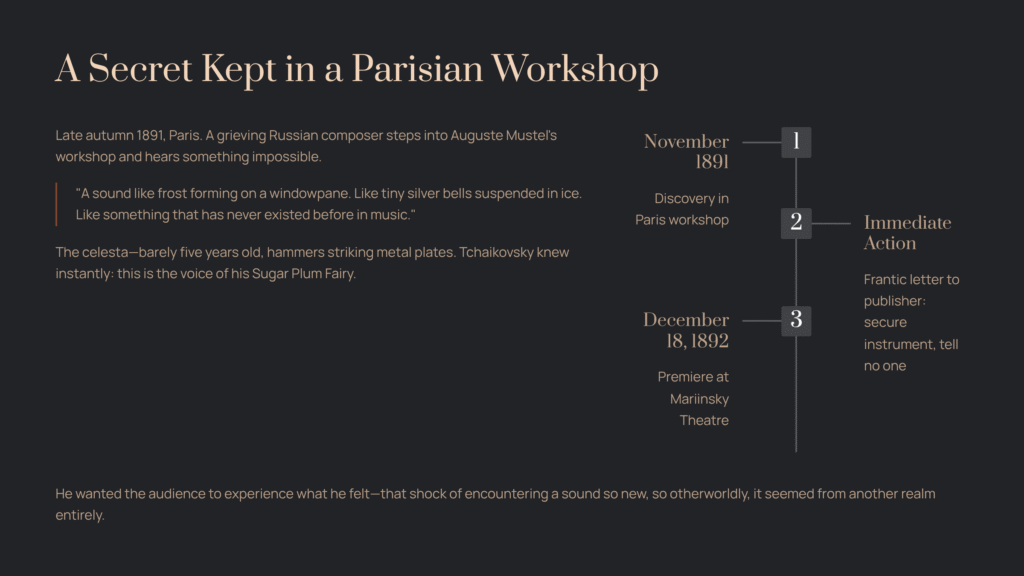

Picture this: late autumn 1891, Paris. A fifty-one-year-old Russian composer steps into Auguste Mustel’s instrument workshop, still carrying the weight of his sister’s recent death. He’s there on business, really—scouting for something, anything, that might capture the magic he’s struggling to compose for his new ballet. And then he hears it.

A sound like frost forming on a windowpane. Like tiny silver bells suspended in ice. Like—and this is what stops his breath—something that has never existed before in music.

The celesta. A keyboard instrument barely five years old, its hammers striking metal plates instead of strings. Tchaikovsky stands there, listening, and in that moment, he knows: this is the voice of his Sugar Plum Fairy.

What happens next is one of classical music’s most beautiful secrets. Tchaikovsky writes to his publisher immediately, almost frantically: secure this instrument, tell no one, keep it hidden until the premiere. He wants the audience to experience what he just felt—that shock of encountering a sound so new, so otherworldly, that it seems to come from another realm entirely.

That premiere happened on December 18, 1892, at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. When the celesta’s first notes pierced through the orchestra, the audience didn’t just hear music. They heard the impossible made audible.

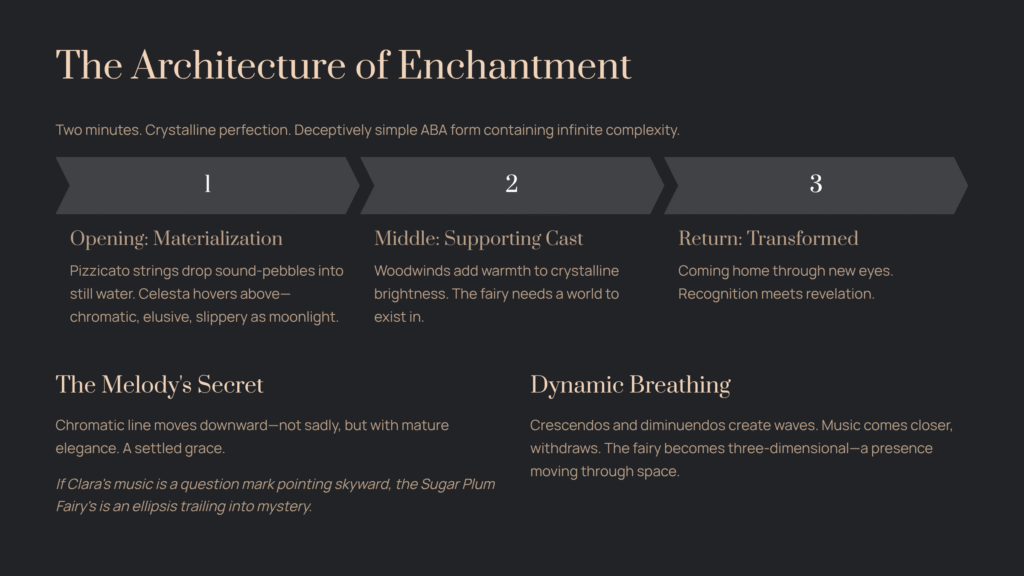

The Architecture of Enchantment

But let’s step back from that magical moment and understand what Tchaikovsky actually built with this newfound voice.

The Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy runs barely two minutes. Yet within that brief span, it contains more crystalline perfection than some symphonies achieve in forty. The structure is deceptively simple: an ABA form, the kind you learn about in music theory class. A theme, a contrasting middle section, a return to the theme.

Except it’s not simple at all.

The opening doesn’t announce itself. It materializes. Pizzicato strings—plucked, not bowed—create a whisper of anticipation. They’re not playing chords; they’re dropping tiny sound-pebbles into still water, watching the ripples spread. And then, hovering above this delicate surface, the celesta enters.

The melody itself is chromatic, meaning it moves through half-steps rather than following a traditional scale. This gives it that slippery, elusive quality—like trying to grasp moonlight. Each note leads inevitably to the next, yet the destination always feels surprising. It’s the musical equivalent of a fairy’s movement: graceful, continuous, slightly otherworldly.

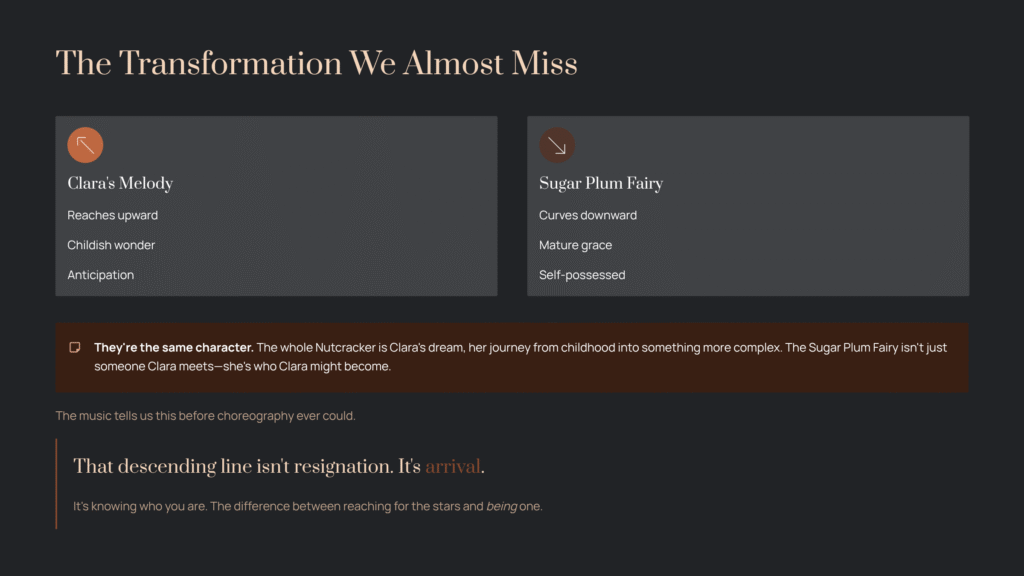

What makes this chromatic line so effective is its shape. Unlike Clara’s ascending, hopeful theme from Act I, the Sugar Plum Fairy’s melody tends downward. Not sadly—never that. But with a kind of mature elegance, a settled grace. If Clara’s music is a question mark pointing skyward, the Sugar Plum Fairy’s is an ellipsis trailing into mystery.

Throughout, Tchaikovsky employs crescendos and diminuendos—waves of sound that swell and recede. The music breathes. It comes closer, then withdraws. This dynamic shaping does something crucial: it gives the fairy depth, makes her three-dimensional. She’s not just a pretty sound; she’s a presence that moves through space.

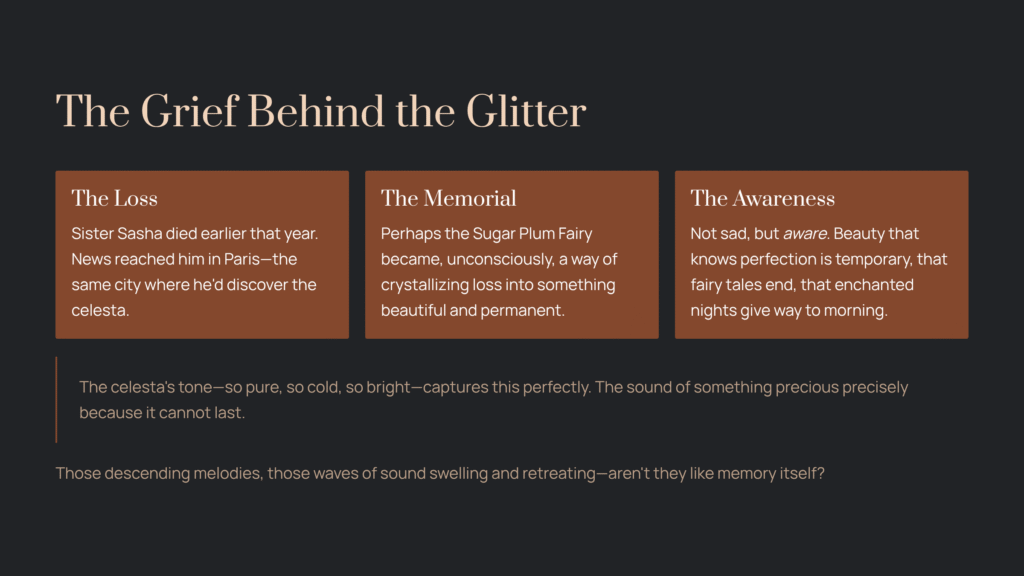

The Grief Behind the Glitter

Here’s something the concert hall doesn’t tell you: Tchaikovsky composed this while mourning.

His beloved sister Sasha—Alexandra Davydova—had died earlier that year. The news reached him in Paris, the same city where he’d discover the celesta. Some biographers suggest this isn’t coincidence. That perhaps the Sugar Plum Fairy became, unconsciously, a memorial. A way of crystallizing loss into something beautiful and permanent.

Listen again with this knowledge. Doesn’t that descending melody take on new meaning? Those moments when the music swells and then retreats—aren’t they like memory itself, coming in waves?

I’m not saying the piece is sad. It isn’t. But there’s a quality to its beauty that feels… aware. As if it knows that perfection is always temporary, that fairy tales end, that even the most enchanted nights give way to morning. The celesta’s tone—so pure, so cold, so bright—captures this perfectly. It’s the sound of something precious precisely because it cannot last.

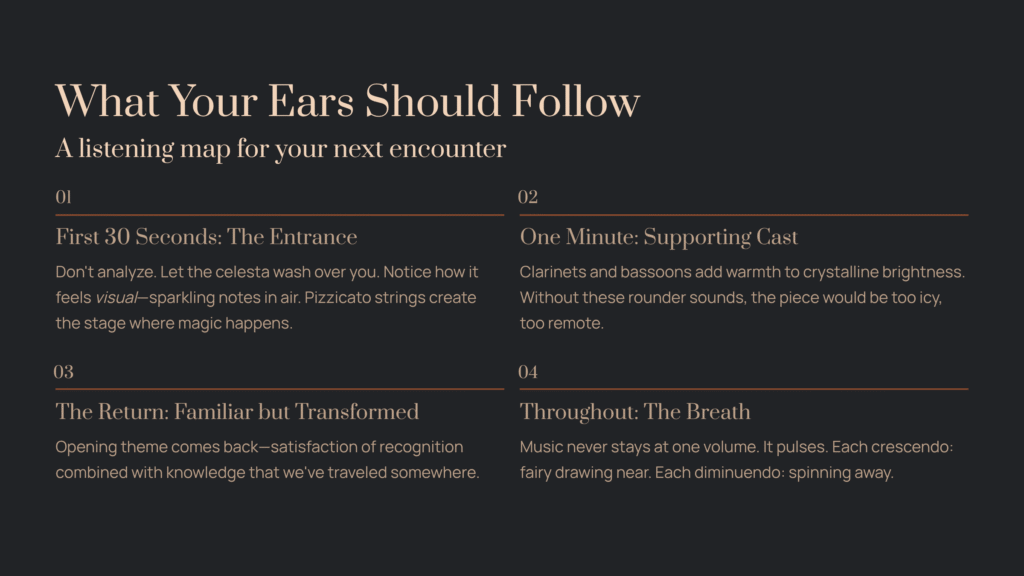

What Your Ears Should Follow

Let me give you a map for your next listening.

First thirty seconds: The entrance

Don’t try to analyze. Just let that celesta tone wash over you. Notice how it feels almost visual—like you can see the notes sparkling in air. The pizzicato strings underneath? They’re not accompaniment; they’re the stage, the space where magic happens.

Middle section: The supporting cast

Around the one-minute mark, listen for the woodwinds. Clarinets and bassoons join the conversation, adding warmth to the celesta’s crystalline brightness. This is crucial: without these lower, rounder sounds, the piece would be too icy, too remote. Tchaikovsky knew this. The fairy needs a world to exist in.

The return: Familiar but transformed

When the opening theme comes back, it should feel both like coming home and like seeing home through new eyes. That’s the gift of ABA form when done right—the satisfaction of recognition combined with the knowledge that we’ve traveled somewhere.

Throughout: The breath

Pay attention to dynamics. The music never stays at one volume. It pulses. This is what makes it alive rather than mechanical. Each crescendo is the fairy drawing near; each diminuendo is her spinning away.

Try This

Put on your best headphones. Close your eyes. And for these two minutes, imagine you’re in that 1892 premiere audience. You’ve never heard a celesta before. You have no idea what’s making this sound. You only know that something impossible is happening—that music has found a new color, that the orchestra has learned to paint with frost and starlight.

That’s what Tchaikovsky gave us. Not just a ballet number. Not just a clever use of a new instrument. But a moment when music expanded its vocabulary, when what seemed possible in sound suddenly grew larger.

Or try this: walk outside on a clear winter night. The kind where stars look sharp enough to cut. Play the piece quietly through earphones. Let it mix with the cold air and the silence. The music won’t seem to be coming from your phone—it’ll seem to be coming from the night itself.

The Transformation We Almost Miss

There’s a detail that often goes unnoticed. The Sugar Plum Fairy’s Dance and Clara’s music from Act I are connected—mirror images, almost. Clara’s melody reaches upward, full of childish wonder and anticipation. The Sugar Plum Fairy’s melody curves downward, mature and self-possessed.

But they’re the same character. The whole Nutcracker is Clara’s dream, her journey from childhood into something more complex. The Sugar Plum Fairy isn’t just a character Clara meets—she’s who Clara might become. The music tells us this before the choreography ever could.

That descending line isn’t resignation. It’s arrival. It’s knowing who you are. It’s the difference between reaching for the stars and being one.

What Remains

Since 1892, the celesta has become indispensable. Film composers reach for it whenever they need to evoke magic, innocence, or memory. It’s in Harry Potter, in countless Christmas movies, in music boxes and video games. Mustel’s workshop invention became the sound of wonder itself.

But it all started here. With a grieving composer in Paris, a new instrument that sounded like frozen light, and two minutes of music that proved perfection doesn’t need to explain itself—it only needs to be.

The next time you hear those opening notes—and you will, because they’re everywhere now—remember that first audience. Remember what it’s like to hear something utterly new. Let yourself be surprised, even though you know what’s coming.

Because that’s the real magic of the Sugar Plum Fairy. No matter how many times we encounter her, she never becomes ordinary. The celesta’s voice is still inhuman, still otherworldly, still sounds like it belongs to some realm we can only visit in dreams.

Tchaikovsky kept his secret for less than a year. But what he created with that secret? That’s been enchanting us for more than a century. And it shows no signs of stopping.

Two minutes. One instrument. Infinite starlight.