Table of Contents

The Secret Behind the Canvas

What if I told you there’s a piece of music that was deliberately designed to hide its meaning?

In 1911, at his country estate Ivanovka, Rachmaninoff composed something unusual. He called it an “Étude-Tableau”—a picture study, a painted exercise. But when people asked him what the picture showed, he refused to answer. “I do not believe in the artist unveiling too much of his images,” he said. “Let the listener paint his own pictures as to what it most suggests.”

This wasn’t modesty. It was a philosophy. Rachmaninoff believed that music should trigger something personal in each listener, something that belonged to them alone. He gave us the colors, the brushstrokes, the light—but the image? That was ours to complete.

The Étude-Tableau Op. 33 No. 2 in C major is perhaps the most luminous of these hidden paintings. Just two and a half minutes long, it sparkles like sunlight on water, flows like a stream catching the afternoon glow. Some hear the sea. Others hear light itself. What will you hear?

When Water Becomes Sound

The piece opens with something that feels less like a melody and more like a shimmer—a rippling current of notes in 12/8 time. The left hand establishes a pattern of sixteenth-note arpeggios, an endless cascade that never quite settles. It’s the musical equivalent of watching light break and scatter across a moving surface.

This is what we call toccata style in piano music: the art of fingers dancing so quickly, so precisely, that individual notes blur into luminous texture. But here’s what makes this étude special among Rachmaninoff’s often turbulent works—it isn’t about drama or storm. It’s about transparency. It’s about seeing through the water to something beneath.

The right hand enters with a melody that feels almost shy at first, emerging from the arpeggiated flow like a face appearing in refracted light. There’s a gentleness here that feels unusual for Rachmaninoff, whose music so often grapples with darker passions. In C major, the brightest of keys, he gives us something that feels like permission to simply be present with beauty.

The Architecture of Light

Now, I need to tell you something technical, but stay with me—it matters for how you’ll hear this piece.

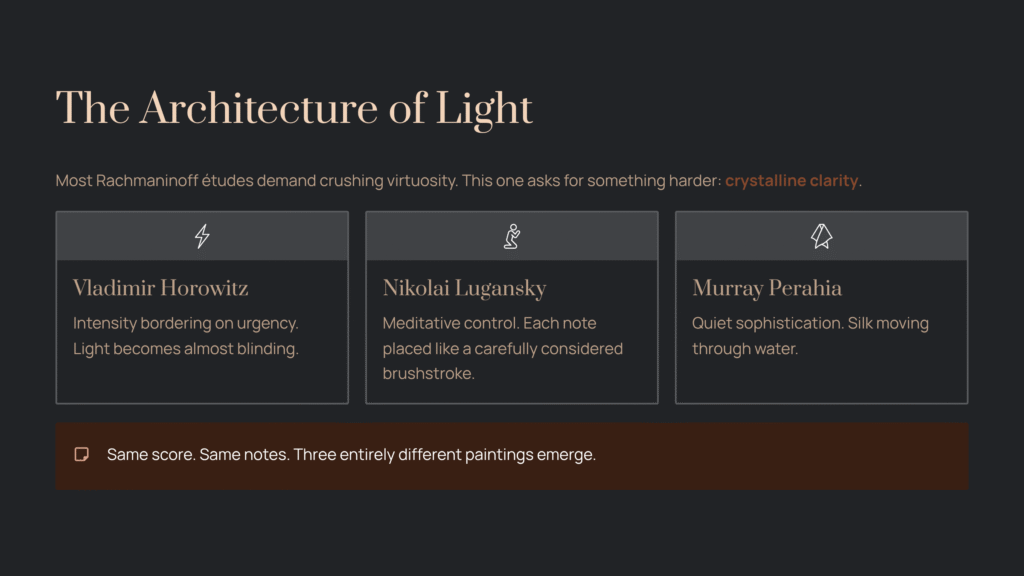

Most Rachmaninoff études demand extraordinary things from a pianist: huge leaps across the keyboard, crushing fortissimos, hands crossing in impossible tangles. But Op. 33 No. 2 makes a different demand. It asks for something harder than virtuosity. It asks for crystalline clarity.

Every note must be heard. Every finger must strike with exactly the right weight, the right timing, so that the entire texture becomes transparent—so you can see through it. Like how you can see pebbles at the bottom of a clear stream, each note in this étude must remain distinct even as hundreds of them rush past.

This is why listening to different pianists play this piece is so revealing. When Vladimir Horowitz performs it, he brings an intensity that borders on urgency—the light becomes almost blinding. Nikolai Lugansky, by contrast, approaches it with a kind of meditative control, each note placed like a carefully considered brushstroke. Murray Perahia finds elegance in it, a quiet sophistication that feels like watching silk move through water.

The same score. The same notes. But three entirely different paintings emerge.

The Hidden Journey

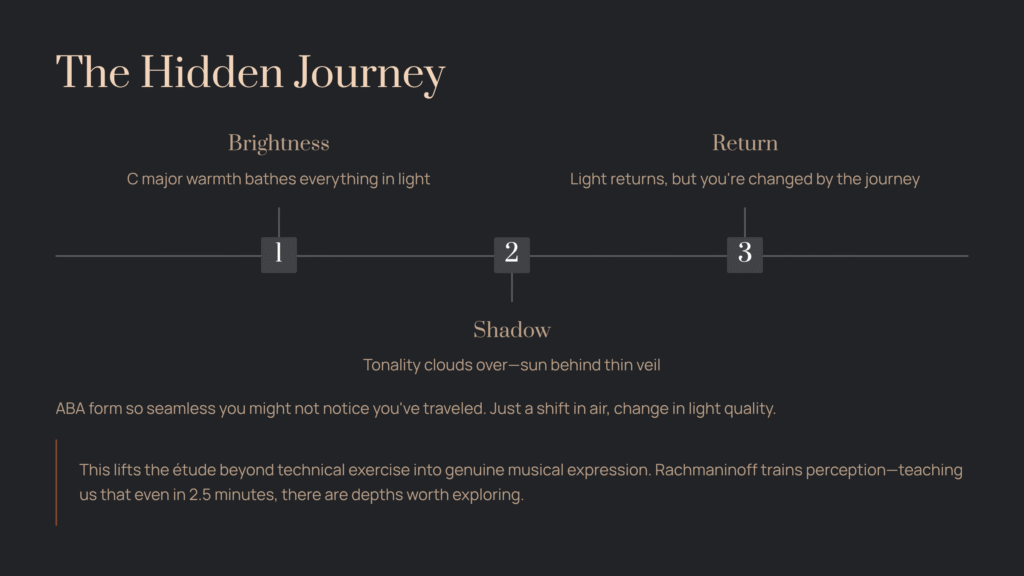

Around the midpoint of the piece—you’ll feel it rather than need a timestamp—something shifts. The brightness dims. The C major tonality that has bathed everything in warmth suddenly clouds over. It’s not dramatic, not a storm. More like a passing shadow, a moment when the sun slips behind a thin veil of cloud.

And then, just as subtly, the light returns.

This is the hidden architecture of the piece, what musicians call ABA form: brightness, shadow, brightness again. But Rachmaninoff does it so seamlessly, with such gentle transitions, that you might not notice you’ve traveled anywhere at all. You just feel something—a shift in the air, a change in the quality of light—and then you’re back where you started, but somehow changed by the journey.

This is what lifts the étude beyond mere technical exercise into the realm of genuine musical expression. Rachmaninoff isn’t just training fingers here. He’s training perception. He’s teaching us that even in the space of two and a half minutes, even in something as seemingly simple as flowing water and reflected light, there are depths worth exploring.

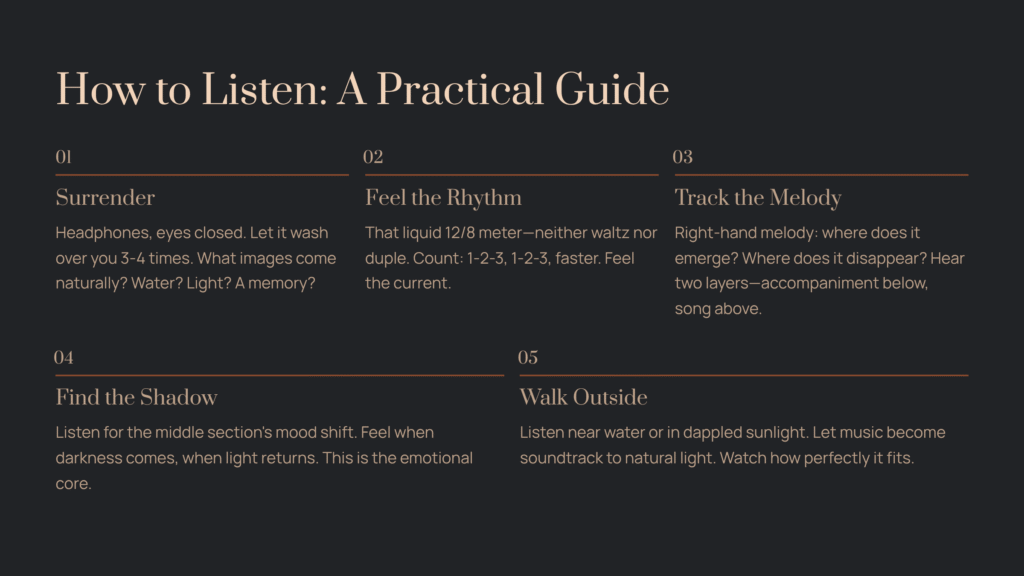

How to Listen: A Practical Guide

Let me offer you some ways into this piece, some doorways you might try:

First, just let it wash over you. Put on headphones, close your eyes, and let the piece play three or four times without trying to analyze anything. Notice what images come to you naturally. Water? Light? A memory of a specific place? Don’t judge these images. They’re yours. They’re what Rachmaninoff wanted you to find.

Then, listen for the rhythm. That 12/8 meter creates a pulse that’s neither purely triple time (like a waltz) nor clearly duple. It’s liquid. Try counting along: 1-2-3, 1-2-3, but faster than you’d count in three. Feel how it propels the music forward like a current you can’t quite resist.

On your third or fourth listening, track the right-hand melody. Where does it emerge from the texture? Where does it disappear back into the flow? The moment you start hearing this as two distinct layers—the accompaniment and the melody—the whole piece will suddenly make more sense. You’ll understand that Rachmaninoff is creating a kind of sonic double-exposure: the constant motion underneath, the song above.

Now listen for that middle section, that moment when the mood shifts darker. Can you feel when it happens? Can you feel when the light returns? This is the emotional core of the piece—this journey from brightness through shadow and back to light. Once you can feel this arc, you’ve understood something essential about how Rachmaninoff structures emotion in time.

Finally, try this: Listen to the piece while walking outside, preferably near water or in dappled sunlight. Let the music become a soundtrack to the natural play of light around you. You might be surprised how perfectly it fits, how it seems to illuminate details you wouldn’t otherwise notice.

What the Music Leaves Unsaid

Rachmaninoff described this étude as having “nostalgic and expressive melodies.” But nostalgia for what? Expression of what feeling, exactly?

He never said. And I think this was the point.

There’s something profound in a piece of music that refuses to pin itself down, that insists on remaining open to interpretation. In a world that increasingly demands that everything be named, categorized, explained, here is a piece that says: “You complete this. You decide what this means.”

Maybe you hear the Black Sea coastline where Rachmaninoff spent summers. Maybe you hear morning light in a place you once knew. Maybe you hear something that has no visual equivalent at all—just pure sensation, pure emotion, existing in that strange territory that only music can access.

I’ve listened to this étude hundreds of times, and I still discover new things in it. New hesitations in the melody I never noticed. New ways the left hand seems to push against or support the right. New emotional shadings in that middle section’s shadows.

The piece never exhausts itself because it was never meant to be solved. It was meant to be experienced, again and again, each time revealing something different depending on who we are in that moment of listening.

The Gift of Transparency

If there’s one thing I want you to take away from this étude, it’s this: Sometimes the most beautiful things are the ones we can see through.

Rachmaninoff could have written something dense, complex, impenetrable. He certainly knew how. But instead, he chose to create something transparent—music where every note is visible, where the structure is simple, where the emotion is clear even if the specific image remains mysterious.

In just 150 seconds, this small piece teaches us something about how to listen, how to be present with beauty without needing to possess it or fully understand it. It teaches us that music doesn’t always need to overwhelm us to move us. Sometimes a shimmer of light on water is enough.

So put on your headphones. Find a quiet moment. Let those arpeggios begin their endless cascade. And paint your own picture—the one only you can see.

That’s what Rachmaninoff wanted all along.