📑 Table of Contents

There is a peculiar silence that descends upon a house when a child sleeps.

In 1840, Franz Liszt—the most celebrated pianist in Europe, the man who made audiences faint with his thunderous octaves and impossible arpeggios—found himself standing in that silence. Before him lay his infant son Daniel, barely a year old, and in that moment, none of his technical brilliance mattered. What emerged from his fingers was something entirely different: a simple prayer, a musical whisper meant for one small, sleeping listener.

This tender sketch would eventually become Hymne de l’enfant à son réveil (Hymn of the Child at Awakening)—a piece so quiet, so deliberately un-virtuosic, that it seems almost impossible it came from the same hands that conquered every concert hall in Europe. Yet perhaps that is precisely the point. Some music isn’t meant to conquer. Some music is meant to cradle.

A Prayer That Grew Wings

The journey of this piece mirrors the complex emotional landscape of Liszt’s own life. The original 1840 version, simply titled Prière d’un enfant à son réveil (A Child’s Prayer at Awakening), was an intimate lullaby. But Liszt, ever the romantic maximalist, couldn’t leave well enough alone.

By 1846, he had discovered Alphonse de Lamartine’s poem of the same name—a meditation on a child’s first waking moments, that liminal space between dreams and daylight where the divine feels close enough to touch. Lamartine’s verses spoke of a child observing the world with fresh wonder: the sun that rises without being asked, the sparrows that receive their feathers, the fountains that never run dry. In these small miracles, the child senses something vast and tender watching over everything.

Liszt set these words for chorus and organ, transforming his private lullaby into a communal hymn. Then, in 1847, during a transformative stay at Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein’s Ukrainian estate, he created the piano version we know today. It was a period of profound change. Liszt was thirty-six, exhausted from years of relentless touring, and beginning to contemplate a different kind of life—one centered on composition and spiritual reflection rather than applause.

The estate at Woronińce became his sanctuary. There, surrounded by autumn fields and the quietude of rural Ukraine, Liszt completed much of his Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, the ten-piece cycle that would house this gentle prayer as its sixth movement.

Listening Through a Child’s Eyes

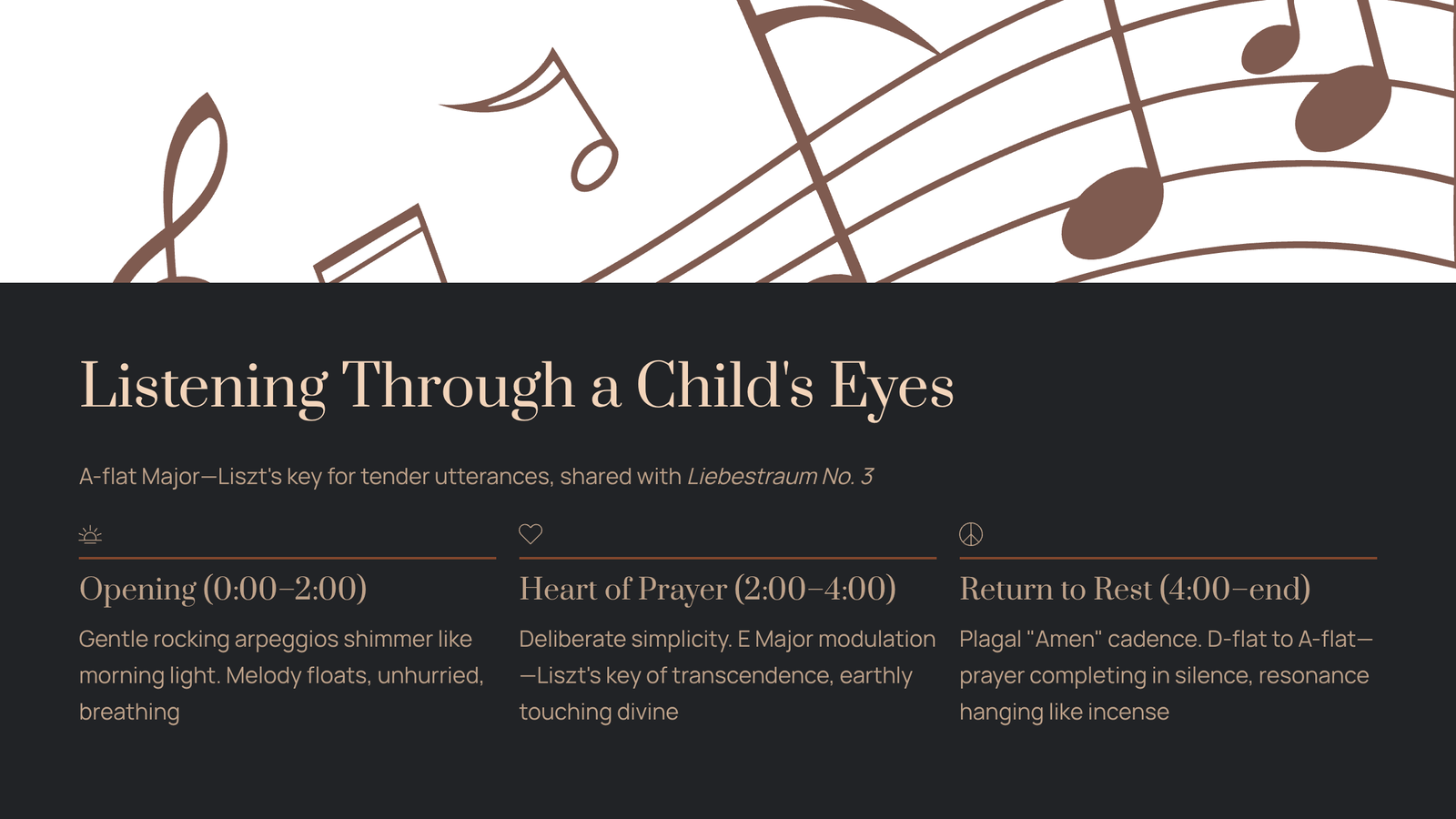

The piece opens in A-flat Major—a key Liszt reserved for his most tender utterances. It’s the same warm, dream-suffused tonality of his famous Liebestraum No. 3, and the resemblance is no accident. Both pieces share an opening melodic contour so similar they might be siblings, one singing of earthly love, the other of divine connection.

The Opening (0:00–2:00): Listen for how the left hand creates a gentle, rocking motion—arpeggios that shimmer like morning light through curtains. The melody floats above, unhurried, singing in long, sustained tones that seem to breathe. There’s no urgency here. A child waking has no appointments to keep.

The Heart of the Prayer (2:00–4:00): As the piece develops, notice how the texture remains deliberately simple. Where another Romantic composer might pile on dramatic flourishes, Liszt holds back. The harmony gently expands, touching on secondary keys like small discoveries—Oh, look at this flower. Oh, feel this warmth. When the music modulates toward E Major, pay attention. In Liszt’s personal musical vocabulary, E Major was the key of transcendence, of moments when the earthly touches the divine.

The Return to Rest (4:00–end): The piece concludes not with the traditional dominant-to-tonic resolution that creates a sense of finality, but with a plagal cadence—the so-called “Amen” progression. D-flat Major melts into A-flat Major like a prayer completing itself in silence. The final notes don’t so much end as dissolve, leaving resonance hanging in the air like incense.

What the Critics Missed

Contemporary critics didn’t quite know what to do with this piece. Compared to Liszt’s showstopping Hungarian Rhapsodies or the thunderous Funérailles (which immediately follows in the cycle), Hymne de l’enfant seemed almost too simple, too sentimental. Some called it naive.

But perhaps they were listening with the wrong ears. The musicologist Leslie Howard, who recorded every note Liszt ever wrote, described the piece as possessing “exquisitely refined melodies.” The simplicity isn’t a limitation—it’s a deliberate restraint, the hardest kind of simplicity to achieve. Any virtuoso can play fast. Few can play this slowly, this vulnerably, without the music collapsing under its own quietness.

There’s another layer modern listeners can appreciate that Liszt’s contemporaries couldn’t. Daniel, the infant who inspired the original sketch, would die in 1859 at just twenty years old. Liszt never got to see his son grow into middle age. The prayer he composed for a sleeping child became, in retrospect, a kind of protective blessing that couldn’t protect anything—a father’s hope preserved in amber, forever young, forever waking.

Finding Your Own Morning

This piece works beautifully as actual morning music. Try this: before checking your phone, before the day’s demands start their clamor, put on a recording and simply listen. Let the arpeggios wash over you like first light.

For pure tenderness: Seek out Hugh Tinney’s Hyperion recording, which treats the piece as intimate confession.

For architectural clarity: Alexander Djordjevic’s recent interpretation brings out the structural elegance beneath the surface simplicity.

For meditative depth: Zoltán Thurzó’s measured tempo allows each harmonic shift to breathe fully.

Notice how your breathing naturally slows. Notice how the piece creates space around itself—how the silences between phrases feel as important as the notes themselves.

The Courage to Be Small

In our age of constant noise and algorithmic maximalism, there’s something radical about music this quiet. Liszt, who could have out-composed anyone in terms of technical display, chose instead to write something a child might hum. He set aside his reputation as the greatest pianist alive to compose a prayer that required nothing but sincerity.

Hymne de l’enfant à son réveil reminds us that sometimes the most profound spiritual experiences come not in cathedrals but in nurseries, not through thunder but through whispers. It suggests that wonder—real, unironic wonder at sunlight and sparrows and the simple fact of waking—is not childish but childlike. And perhaps that distinction makes all the difference.

The piece ends, as all good prayers end, in something close to silence. Not the silence of absence, but the silence of presence—the quiet that remains after someone beloved has finished speaking, before the world rushes back in.

Listen to it tomorrow morning. See what wakes in you.