📑 Table of Contents

There are pieces of music that feel like eavesdropping on someone’s most private moment. Robert Schumann’s Geistervariationen (Ghost Variations) Theme is one of them—a melody so intimate, so fragile, that listening to it feels almost like holding your breath, afraid that any sudden movement might shatter something irreplaceable.

This isn’t just a piece of music. It’s a window into the final coherent thoughts of a genius on the edge of darkness. And somehow, in that twilight, Schumann created something of heartbreaking beauty.

The Night Angels Came to Schumann

On the night of February 17, 1854, something extraordinary happened in the Schumann household in Düsseldorf. Robert Schumann—one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era—suddenly rose from his bed, convinced that angels were singing a melody to him.

His wife Clara, herself a legendary pianist, recorded the moment in her diary: Robert claimed that Schubert and Mendelssohn, both deceased, were dictating music from beyond the grave. He rushed to his desk and wrote down what he heard—a simple, hymn-like theme in E-flat major.

What makes this story even more poignant? The melody Schumann believed was divine revelation was actually his own. He had used nearly the same theme in his Violin Concerto just four months earlier. But in his deteriorating mental state, he couldn’t recognize his own voice.

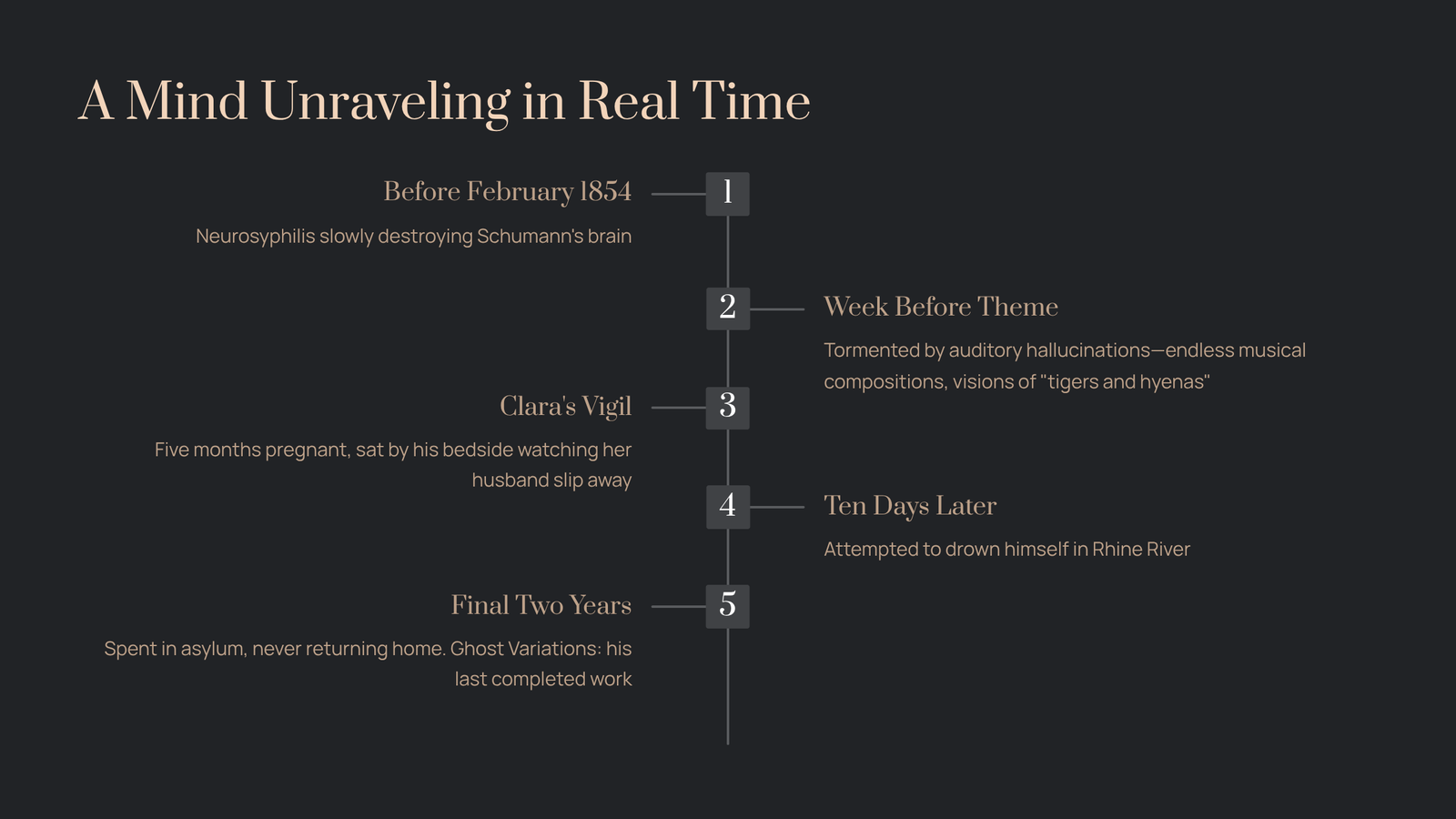

A Mind Unraveling in Real Time

To understand this Theme, we need to understand what February 1854 meant for Schumann. He had been suffering from what we now believe was neurosyphilis—a condition that was slowly destroying his brain.

For over a week before writing this Theme, Schumann had been tormented by auditory hallucinations. Not just ringing in his ears, but fully formed musical compositions playing endlessly in his mind. Some felt heavenly; others terrified him, accompanied by visions of what he called “tigers and hyenas” attacking him.

Clara, five months pregnant at the time, sat by his bedside night after night, watching her husband slip away.

Ten days after completing the variations on this Theme, Schumann would attempt to drown himself in the Rhine River. He would spend the remaining two years of his life in an asylum, never returning home. The Ghost Variations became his last completed work—a final letter from a brilliant mind saying goodbye to music itself.

What Makes This Theme So Moving?

Marked Leise, innig (quiet, heartfelt), the Theme unfolds over just 28 bars. On paper, it seems almost too simple—a chorale-like melody moving gently downward, supported by warm harmonies in E-flat major.

But simplicity here isn’t limitation; it’s distillation. Every note carries weight.

Pianist Jonathan Biss describes it perfectly: “The Theme hesitates, as if unable to release certain notes or suspensions. Nothing seems to happen. But this very absence of events heightens the meaning of everything that does occur. Each altered note, each suspension, stops our breath.”

The melody constantly reaches upward—toward something it can never quite grasp. There’s longing in every phrase, a yearning for connection, for understanding, for peace that remains just out of reach. It’s the musical equivalent of extending your hand toward someone who’s already fading away.

A Listening Guide: Finding Your Way In

If you’re new to this piece, here’s how to approach it:

First Listen: Feel the Atmosphere

Don’t try to analyze anything. Just let the music wash over you. Notice the quietness, the sense of something precious being whispered in confidence. This is music that doesn’t demand your attention—it invites your intimacy.

Second Listen: Follow the Melody’s Journey

The Theme begins with a simple descending line: G to F to E-flat. This three-note motive becomes the DNA of everything that follows. Listen for how it returns, transforms, reaches upward, and always eventually falls back down.

Third Listen: Notice the Hesitations

Pay attention to the spaces between phrases, the moments where the music seems to pause mid-thought. These aren’t accidents—they’re the musical equivalent of someone trying to find the right words for something they know they’ll never be able to fully express.

Why Clara Hid This Music for 85 Years

After Schumann’s death in 1856, Clara made a decision that puzzles music lovers to this day: she refused to publish the Ghost Variations. For 85 years, this music remained hidden from the world.

Why? Scholars suggest several possibilities. Perhaps she feared it would expose her husband’s mental fragility. Perhaps she thought it was artistically inferior—Brahms apparently shared this view initially. Or perhaps it was simply too personal, too painful, to share.

Whatever her reasons, the music finally emerged in 1939. And what listeners discovered wasn’t the rambling of a broken mind, but something remarkably coherent—tender, wise, and deeply moving.

As Biss puts it: “Clara was afraid—for herself, and for him. She suppressed its publication, fearing it would reveal weakness. She couldn’t hear the essence through the fear. But we don’t have to make the same mistake. A window this deep into the soul of a great artist is a rare gift.”

Recommended Recordings

For Your First Experience:

András Schiff (ECM, 2010) – Crystal-clear, emotionally restrained, letting the music speak for itself. Perfect for understanding the Theme’s architecture.

For Emotional Depth:

Jonathan Biss (various live recordings) – More dramatic, with deeper rubato and philosophical weight. His program notes alone are worth seeking out.

For Historical Context:

Jörg Demus (1973) – The recording that first gave this work its “Ghost Variations” nickname. Reflective and spiritual in approach.

For a Modern Perspective:

Eric Lu – Brings a contemporary sensibility while honoring the music’s sacred quality.

The Echoes That Remain

There’s something almost miraculous about the Ghost Variations Theme. Written by a man who could no longer distinguish his own thoughts from angelic visitation, it somehow transcends its tragic origin.

In those quiet, reaching phrases, we hear something universal: the human longing to be known, to be understood, balanced against the terror of true vulnerability. Schumann wanted to be seen—and was terrified of what others might find.

Perhaps that’s why this music resonates so deeply with listeners who discover it. In Schumann’s final coherent musical thought, we recognize something of our own solitude, our own reaching toward what we cannot quite grasp.

The angels Schumann heard that February night may have been hallucinations. But the beauty he captured was absolutely real. And nearly 170 years later, it still has the power to stop us in our tracks and remind us how precious, how fragile, how mysteriously beautiful the creative human spirit can be.

Listen to this piece when you need music that understands loneliness without trying to fix it—music that simply sits beside you in the quiet and says, “I know.”