📑 Table of Contents

There’s a moment in this piece—around thirty seconds in—where the French horn leaps upward like someone calling out across a sunlit meadow. It’s the kind of sound that makes you smile before you even realize you’re doing it. And behind that joyful melody lies one of classical music’s most delightful friendships: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and a horn player who ran a cheese shop.

Yes, really. A cheese shop.

The Horn Player Who Made Mozart Laugh

Joseph Leutgeb wasn’t just any musician. Born in 1732 near Vienna, he was considered one of the finest horn virtuosos of his generation. He premiered works by Haydn, Dittersdorf, and other major composers. He toured Italy with the Mozart family when Wolfgang was still a teenager. And when he decided to settle down in Vienna in 1777, he borrowed money from Mozart’s father Leopold to open a small cheese business on the side.

This detail alone tells you something about Leutgeb’s character. Here was a man celebrated across European courts, yet humble enough to supplement his income selling dairy products. Mozart adored him—and showed it in the most Mozart way possible: by writing “Leutgeb, you ass!” in the margins of his horn concerto manuscripts.

The Horn Concerto No. 4 in E-flat major, K. 495, completed on June 26, 1786, represents the peak of this musical friendship. Mozart was riding high that spring; his opera The Marriage of Figaro had premiered just weeks earlier to thunderous acclaim. Yet amid all that success, he took time to craft another masterpiece for his cheese-selling friend.

Why This Rondo Sounds Like Hunting Horns

The third movement—marked Allegro vivace in 6/8 time—opens with what sounds unmistakably like a hunting call. This isn’t accidental. The French horn evolved directly from actual hunting horns used to coordinate hunters across vast forest estates. By Mozart’s time, those outdoor signals had become stylized into concert hall entertainment, but the connection remained strong.

Listen for these hunting-call fingerprints throughout the movement:

The opening theme features bold upward leaps followed by repeated notes—exactly how a hunter might shout across a valley to signal the chase. The 6/8 meter creates a galloping, bouncing rhythm that evokes horseback riding through countryside. And the horn’s bright, open E-flat major tonality rings out with the clarity of an instrument designed to carry sound across miles of Austrian woodland.

Mozart labeled this work “Ein Waldhorn Konzert” in his personal catalog—using “Waldhorn” (forest horn) rather than the more generic term. He wanted listeners to remember where this instrument came from.

The Technical Magic You Can’t See

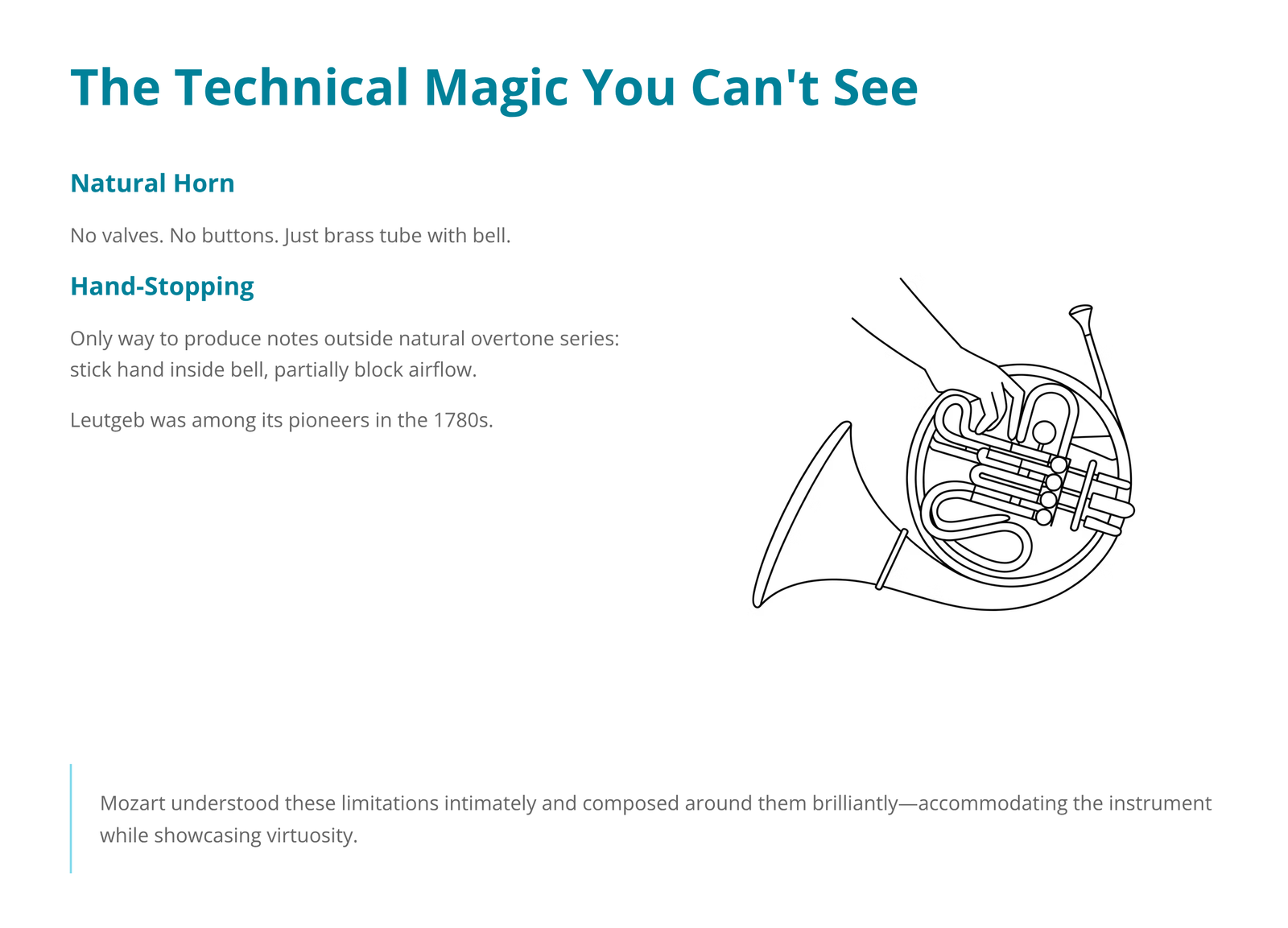

Here’s something remarkable about this movement: Leutgeb played a natural horn. No valves. No buttons. Just a brass tube with a bell, where the only way to produce notes outside the instrument’s natural overtone series was to stick your hand inside the bell and partially block the airflow.

This technique—called hand-stopping—was still relatively new in the 1780s, and Leutgeb was among its pioneers. When you hear the horn navigate through the movement’s various key changes, you’re witnessing a technical feat that modern valve-horn players can barely imagine.

Mozart understood these limitations intimately and composed around them brilliantly. Notice how the main theme emphasizes notes that fall naturally in the horn’s harmonic series—the tonic and dominant triads that ring out most purely. Then notice how the development section pushes Leutgeb into more adventurous territory, demanding quick shifts between open and stopped notes. Mozart was simultaneously accommodating his friend’s instrument and showcasing his virtuosity.

A Listening Journey Through the Movement

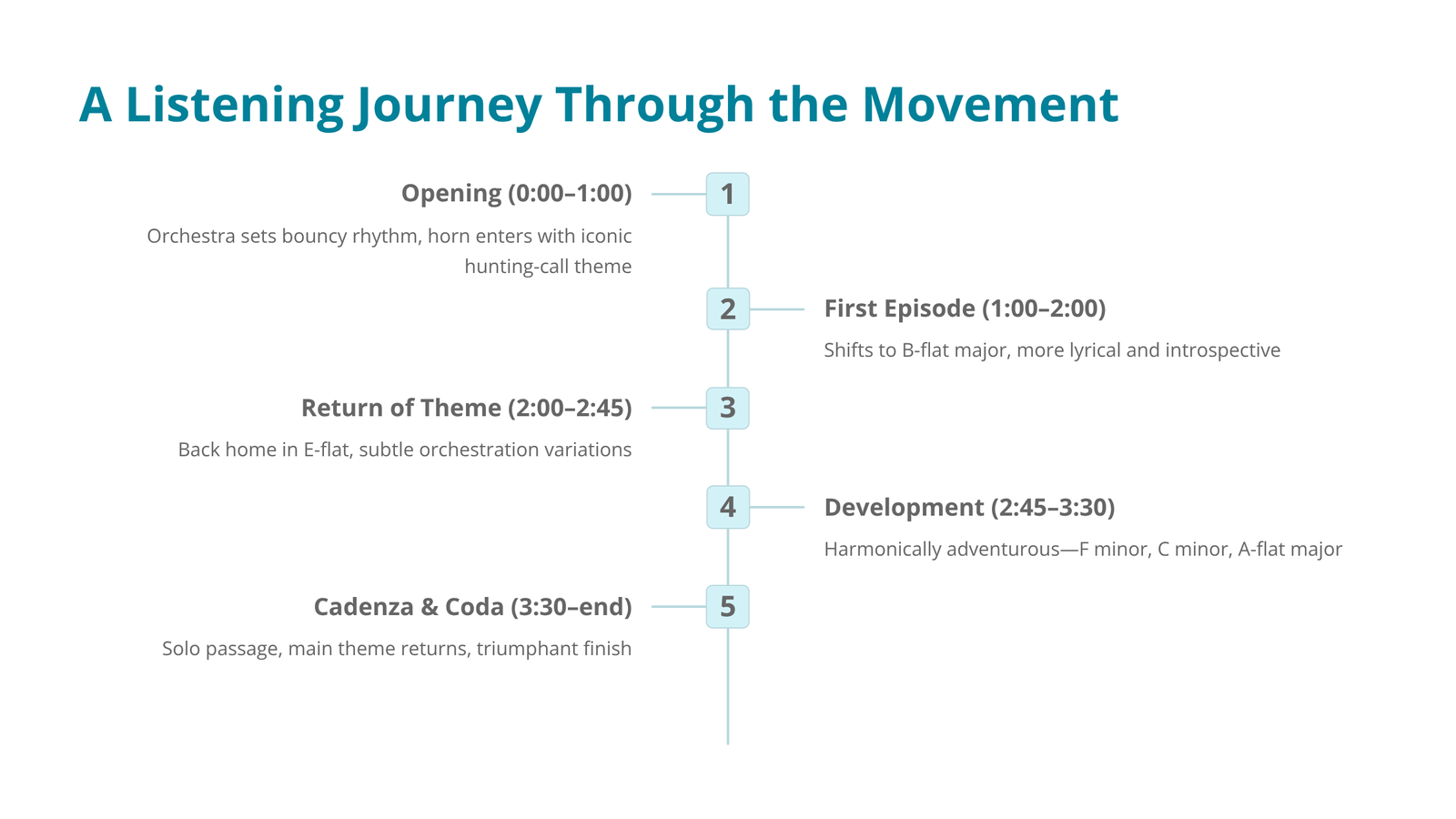

The Rondo unfolds in a clear, satisfying architecture. Here’s what to listen for:

Opening (0:00–1:00): The orchestra sets up a bouncy rhythmic bed, then the horn enters with that iconic hunting-call theme. Pay attention to how jaunty and confident it sounds—this is music that knows exactly where it’s going.

First Episode (1:00–2:00): The music shifts to the dominant key (B-flat major), becoming slightly more lyrical and introspective. The horn sings more than calls here, showing its capacity for beauty beyond mere bravado.

Return of the Theme (2:00–2:45): We’re back home in E-flat, but Mozart varies the orchestration subtly. Listen for small changes in how the strings and oboes interact with the horn.

Development (2:45–3:30): Here’s where things get harmonically adventurous. The music wanders through remote keys—F minor, C minor, A-flat major—creating a sense of temporary disorientation. The horn works hard in this section, and you can almost feel Leutgeb’s hand moving rapidly inside the bell.

Cadenza and Coda (3:30–end): A brief solo passage allows the horn to show off, then the main theme returns one final time. Mozart does something delightful here: the music seems to “get stuck” on a repeated figure, starts again, then rushes toward a triumphant finish.

The Multi-Colored Manuscript Mystery

One famous detail about K. 495 deserves mention. Mozart wrote the manuscript in four different colored inks—red, green, blue, and black—alternating seemingly at random. For years, scholars assumed this was just another way to tease Leutgeb, perhaps to confuse or distract him during performance.

Recent research suggests something more interesting: the colors may have functioned as a primitive form of musical notation, with each color indicating different expressive qualities. Red might mark thematic material. Blue could signal dynamic emphasis. We may never know for certain, but it’s a reminder that Mozart’s playfulness often concealed deeper musical thinking.

Which Recording Should You Hear First?

Dennis Brain with Herbert von Karajan (1953): This remains the benchmark recording over seventy years later. Brain’s tone is silvery and elegant, his phrasing impeccable. He captures the movement’s humor without mugging, its technical challenges without showing strain. If you listen to only one version, make it this one.

Barry Tuckwell with London Symphony Orchestra: Brain’s student takes a more muscular approach, with heavier articulation and more forward momentum. Where Brain glides, Tuckwell drives. Both interpretations are valid; hearing them side by side reveals how much room for personality exists within Mozart’s notes.

Radek Baborák on natural horn: For listeners curious about historical performance practice, Baborák’s recording uses a valveless instrument similar to what Leutgeb played. The slightly muffled quality of stopped notes becomes audible, adding an authenticity that modern valve horns smooth away.

Why This Music Endures

In 1964, British comedians Flanders and Swann set the Rondo’s main theme to comic lyrics about the frustrations of learning French horn. Their song “Ill Wind” became a minor hit, introducing Mozart’s melody to audiences who might never have heard it otherwise. The fact that this eighteenth-century tune could seamlessly become a twentieth-century comedy number speaks to its essential catchiness.

But there’s something deeper happening here. This is music about friendship, about the joy of making things for people you care about. Mozart could have phoned in these horn concertos—Leutgeb would have been grateful for anything. Instead, he poured genuine craft and affection into every measure. You can hear that care in the way the melodies fit the instrument so naturally, in the wit of the harmonic surprises, in the satisfying fullness of the final cadence.

Joseph Leutgeb outlived Mozart by two decades, dying in Vienna in 1811. We don’t know if he kept performing the concertos after his friend’s death. But we do know that every horn player since has benefited from their collaboration. The K. 495 Rondo isn’t just a test piece or a recital staple. It’s a love letter, written in four colors of ink, from one creative spirit to another.

Press play. Let that opening hunting call wash over you. And imagine two friends in eighteenth-century Vienna—one a genius composer at the height of his powers, the other a virtuoso horn player who smelled faintly of cheese—laughing together over music that still makes us smile today.