Table of Contents

Have you ever noticed how the most powerful prayers use the same words over and over again? How repetition itself becomes a kind of medicine for the soul?

There’s a three-minute song by Schubert that understands this secret perfectly. It doesn’t try to dazzle you with elaborate melodies or dramatic crescendos. Instead, it does something far more radical: it gives you the same gentle tune again and again, like a hand quietly placed on your shoulder, until something inside you finally exhales.

Litanei auf das Fest Allerseelen, D.343. Even the title sounds like a prayer whispered in candlelight.

The Young Man Who Already Knew About Endings

- Schubert was only nineteen years old when he composed this music, setting words by Johann Georg Jacobi. Nineteen—an age when most of us are just beginning to understand life, not contemplating its end. Yet somehow, this young composer grasped something profound about grief, memory, and consolation that would take others a lifetime to comprehend.

The occasion? Allerseelen—All Souls’ Day, the Catholic commemoration on November 2nd when the living remember all the departed. Not just saints or heroes, but every soul who has passed beyond the veil. Your grandmother. My childhood friend. The stranger we never knew. All of them, resting somewhere in the great unknown.

But here’s the paradox: this song written for the dead offers its deepest comfort to the living. It’s we who need the reminder that grief doesn’t have to be violent or loud. Sometimes the most profound consolation comes through quiet, steady repetition—like waves on a shore, gradually smoothing the jagged edges of loss.

The Magic of Saying the Same Thing Differently

When you first press play, you might think: “Wait, isn’t this the same melody repeating?” And you’d be right. This is what musicians call strophic form—the same musical phrase returning for each new verse, like a rosary bead passing through your fingers, one after another.

At first glance, this seems almost too simple. In an art form that celebrates complexity and development, why would Schubert just… repeat himself?

But listen more closely. Pay attention to what happens beneath the surface.

Each time that melody returns, the words have changed. New images appear in the text—different sorrows, different memories, different prayers—yet they’re all carried by the same gentle tune. This is Schubert’s genius: he understood that when we’re grieving, we don’t need novelty. We need something familiar to hold onto, something constant while everything else feels uncertain.

Think of it like this: imagine you’re walking the same path through a forest every day. The path doesn’t change, but you notice different things each time—today, morning light through branches; tomorrow, the sound of rain on leaves; the next day, the crunch of frost underfoot. The path is your anchor. The changing seasons are your journey.

That’s what the strophic form does here. The melody is your anchor. The evolving lyrics are your journey through grief.

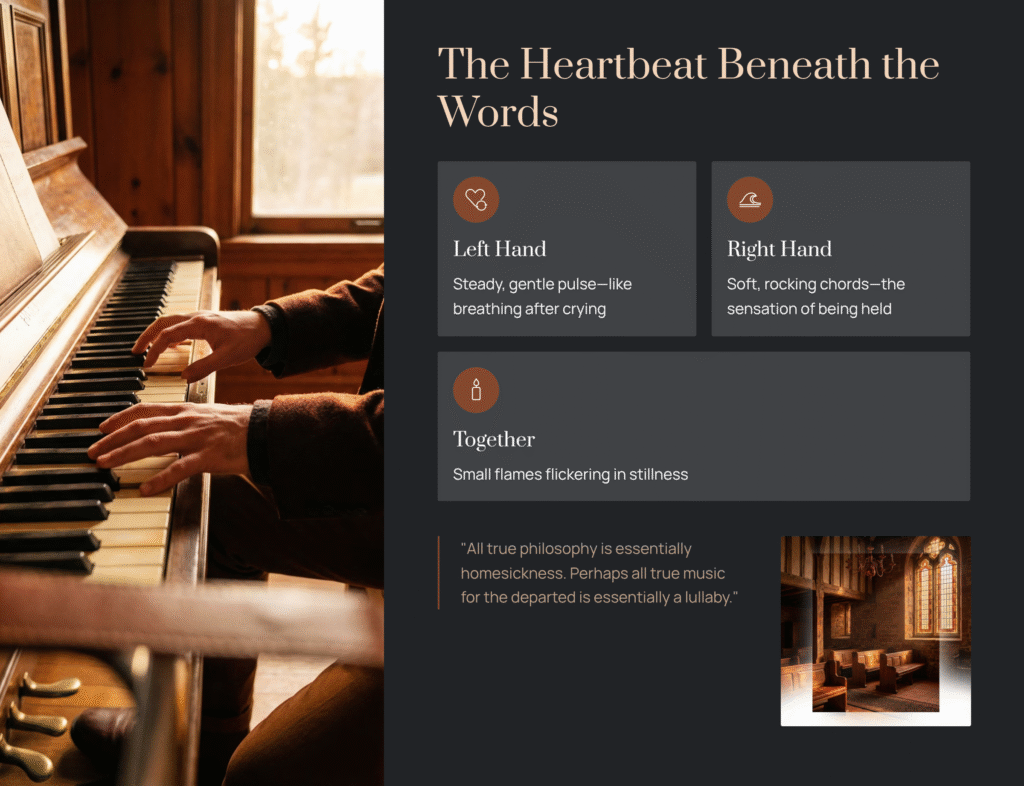

The Heartbeat Beneath the Words

Now, direct your attention to the piano accompaniment. This isn’t mere background music—it’s the beating heart of the entire piece.

In the pianist’s left hand, you’ll hear a steady, gentle pulse. Not dramatic. Not insistent. Just there, like the rhythm of breathing when you’re finally calm after crying. The right hand adds soft, rocking chords that sway back and forth, creating a sensation of being held, being comforted.

Close your eyes and imagine this: you’re in a small chapel, late afternoon, November light filtering through stained glass. Someone is lighting candles, one by one. The piano accompaniment is the sound of those small flames flickering in the stillness. It doesn’t demand your attention—it simply creates a space where grief can exist without being overwhelming.

The German Romantic poet Novalis once wrote that all true philosophy is essentially homesickness. Perhaps all true music for the departed is essentially a lullaby—not to put death to sleep, but to help the living finally rest.

Listen This Way: A Practical Guide

You don’t need to understand German to feel this song’s power, but knowing what to listen for will deepen your experience. Here’s how I’d suggest approaching it:

First listening: Focus on the refrain

Each verse ends with the same profound line:

“Alle Seelen ruhn in Frieden.”

(“All souls rest in peace.”)

Wait for this moment. The singer’s voice often softens here, as if the words themselves are too sacred to disturb. This is the still point around which everything revolves.

Second listening: Track the piano’s conversation

Notice how the pianist’s left and right hands seem to speak to each other. Sometimes they move together, sometimes in gentle counterpoint. It’s like watching two people who’ve known each other for years communicate without words—a glance here, a nod there, complete understanding.

Third listening: Let go of analysis

Now that you know the architecture, forget it. Light a single candle if you can. Dim the lights. Just breathe and let the repetition work its quiet magic. Don’t try to “understand” anything. Let the music be what it is: a prayer, a comfort, a gentle insistence that even in loss, there can be peace.

Three Voices, Three Ways to Hear This Prayer

The beauty of Schubert’s Lieder is that different voices reveal different dimensions of the same music. Here are three approaches, each offering its own path into this piece:

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (Baritone): The Philosopher’s Prayer

When the great German baritone Fischer-Dieskau sings this, you hear every syllable of the German text with crystalline clarity. His voice has gravity, wisdom, the weight of lived experience. This is the version for when you want to understand the words as deeply as the music. Listen late at night, when you’re thinking about life’s big questions.

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (Soprano): The Angel’s Consolation

Schwarzkopf’s luminous soprano transforms the Litanei into something almost ethereal. Her voice seems to descend from somewhere beyond this world, offering comfort that transcends human understanding. If Fischer-Dieskau’s version is earth and wisdom, Schwarzkopf’s is light and grace.

Mischa Maisky (Cello) & Martha Argerich (Piano): Prayer Without Words

Not comfortable with German yet? Start here. When Maisky’s cello takes the vocal line, you realize how much the human voice and the cello resemble each other—both capable of singing, sighing, consoling. The cello’s deep, warm tone carries all the prayer’s emotion without a single word. Sometimes, grief is beyond language anyway.

A Moment to Remember: The Final Verse

Most performances select just three verses from Jacobi’s original nine-stanza poem. The progression is deliberate, moving from acknowledgment to empathy to transcendence:

First verse: “Rest in peace, all souls, whose joys and pains are ended…”

Middle verse (usually the third): “Those who carried unfinished dreams, whose hopes were crushed by life’s burdens—may they, too, find rest…”

Final verse: “In God’s eternal light, may all souls rest in peace…”

Pay special attention to how the singer delivers that final repetition of “Alle Seelen ruhn in Frieden.” By now, these words have been sung multiple times, but they never lose their power. If anything, they’ve accumulated meaning, like a stone polished smooth by a river’s patient flow.

What This Song Remembers

November 2nd, Allerseelen, All Souls’ Day—it’s a date that asks us to remember. But what does it mean to truly remember the departed?

Schubert’s Litanei suggests an answer: remembrance isn’t about clinging desperately to what’s gone. It’s about creating a space—quiet, reverent, gentle—where memory and peace can coexist. It’s about accepting that loss is real and permanent, yet somehow not final. The ones we’ve loved leave an echo in the world, and music like this gives that echo a voice.

I think of all the November 2nds that have passed since 1816. How many people have found solace in these three minutes of music? How many tears have been shed, how many memories honored, how many hearts gradually made whole again, all while these same notes played on?

The strophic form suddenly makes even more sense: the same melody returning year after year, generation after generation, exactly as rituals should return. Some things—comfort, prayer, remembrance—don’t need to be reinvented. They need to be preserved, repeated, passed down like family treasures.

Your Turn to Light a Candle

Tonight, or whenever you’re ready, I invite you to try something. Find a quiet moment. Maybe it’s late evening, maybe early morning before the world wakes up. Dim the lights. If you can, light a single candle—not for religious reasons necessarily, but for the simple beauty of that small flame in darkness.

Press play on whichever version calls to you. Close your eyes.

Let Schubert’s nineteen-year-old genius remind you that it’s okay to grieve, okay to remember, okay to need comfort. Let the same melody wash over you again and again, each repetition smoothing something rough inside you, until you, too, can whisper: Alle Seelen ruhn in Frieden.

All souls rest in peace.

Including, perhaps, something in yourself that’s been restless for too long.