Table of Contents

Melodies Emerging from Infinite Horizons

Some music transports you to another world from the very first note. Borodin’s “In the Steppes of Central Asia” is precisely such a piece. In just seven minutes, we walk across the vast 19th-century Central Asian steppes and witness the miraculous moment when two cultures meet.

The high, transparent melody drawn by the violins feels like an endless sky, while the Russian folk song sung by the clarinet below carries the hearts of soldiers longing for home. And the oriental melody voiced by the English horn touches our ears with mysterious and melancholic beauty.

This is not mere music. It is a cultural dialogue that transcends time and space, a painting rendered in musical notes that captures the beauty of the moment when different worlds encounter one another.

The Dual Life of Alexander Borodin: A Genius’s Extraordinary Story

Alexander Porfiryevich Borodin (1833-1887). While most would think of him as a composer, his primary profession was actually chemistry. As a chemistry professor at the St. Petersburg Medical Academy, he was a true scientist who made significant discoveries in organic chemistry.

Music was literally his “leisure activity.” He reportedly composed only when he was ill or had spare time. Yet this leisure pursuit made him a master whose name will forever remain in Russian music history.

In 1862, he fatefully met Mily Balakirev and joined the Mighty Five. The story of these passionate musicians—Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Cui—united in their mission to create “authentic Russian music” represents one of music history’s most romantic chapters.

Russia’s Orient: Orientalism as a New Musical Language

As 19th-century Russia expanded its empire into the Caucasus and Central Asia, it naturally encountered Eastern cultures. What the Mighty Five discovered during this period was Orientalism. For them, “Oriental elements” became a crucial language for expressing Russian musical identity.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade,” Balakirev’s “Tamara,” and Borodin’s “In the Steppes of Central Asia”—all these masterworks reinterpreted Eastern mysticism through Russian sensibility. They found Russia’s unique musical colors, distinctly different from Western European music.

“In the Steppes of Central Asia” – A Short Film Rendered in Music

Music for the Emperor, Dedicated to Liszt

This work was composed in 1880 for tableaux vivants (living pictures) commemorating the 25th anniversary of Emperor Alexander II’s reign. Though the planned event was canceled, the piece premiered successfully in St. Petersburg under Rimsky-Korsakov’s baton.

Intriguingly, Borodin dedicated this work to Franz Liszt. It was an expression of respect for Liszt, the founder of the symphonic poem genre. Borodin perfectly realized the possibility of “storytelling through music” that Liszt had demonstrated.

The Composer’s Own Listening Guide

Borodin kindly left this explanation in his score:

“In the silence of the monotonous steppes of Central Asia, the unfamiliar sounds of a peaceful Russian song are heard. From the distance, sounds approach of horses and camels, and with them a strange, melancholy oriental melody. A caravan approaches, escorted by Russian soldiers, and passes safely through the vast desert. It slowly disappears. Russian and Asiatic melodies join in common harmony, and the sounds fade away as the caravan disappears in the distance.”

Could there be a more precise listening guide? Borodin kindly taught us exactly how to listen to his music.

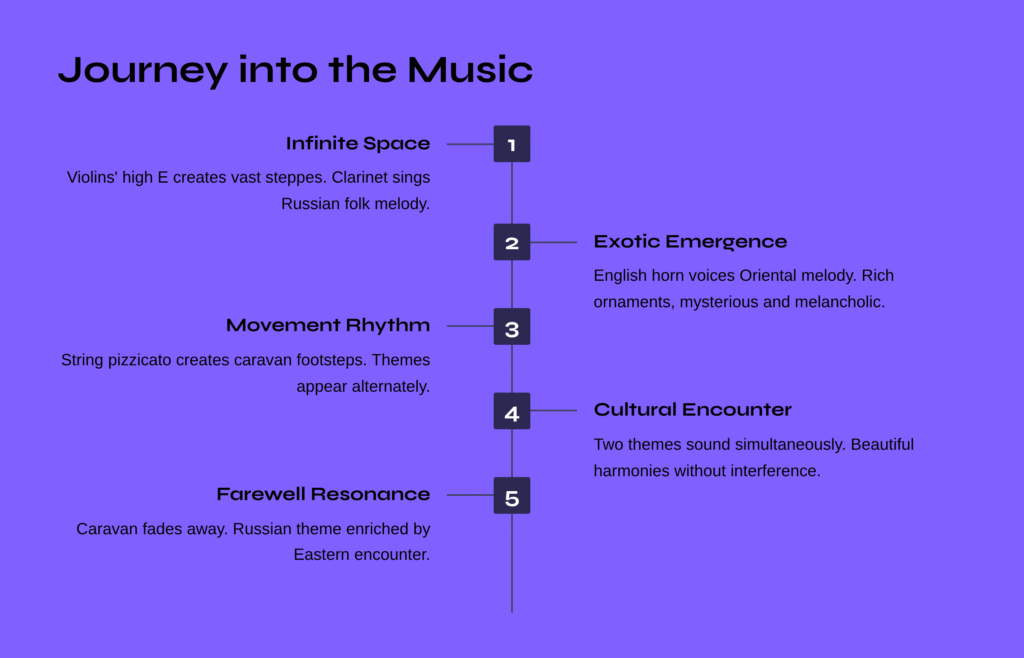

Journey into the Music – Detailed Movement-by-Movement Listening

First Moment: The Silence of Infinite Space

As the piece begins, the violins’ high E welcomes us. This single note pervades the entire work, expressing the vastness of the endless steppes. It feels like a horizon stretching beyond the visible world.

Above this sustained note, clarinet and horn quietly begin singing a Russian folk-style melody. This peaceful, familiar tune represents Russian soldiers singing of home. It carries the unchanging sentiment of homeland even in distant foreign lands.

Second Moment: The Emergence of Exotic Melody

Then from somewhere comes a completely different melody. It’s an Oriental melody played by the English horn—the instrument most favored by the Mighty Five composers when expressing “exotic Orient.”

This melody differs entirely from the Russian theme. Rich with ornaments, serpentine in its melodic line, somehow mysterious and melancholic. Perhaps it’s the song of Central Asian merchants, or a melody of the homeland they long for.

Third Moment: Movement Created by Rhythm

Once the two melodies establish their respective positions, the strings’ pizzicato creates a regular rhythm. These are the footsteps of horses and camels. The sound announces that the caravan is moving slowly but surely.

Over this rhythm, the Russian and Oriental themes appear alternately. It’s as if people from different cultures are cautiously observing each other.

Fourth Moment: The Moment of Encounter and Dialogue

Reaching the middle section, the two themes gradually draw closer. What was initially separated in time now begins to sound simultaneously. This is the moment when two cultures actually meet.

Here Borodin’s contrapuntal mastery shines. The Russian and Oriental themes create beautiful harmonies without interfering with each other. This is not merely technical achievement—it’s a hopeful message that different cultures can achieve harmony.

Fifth Moment: Farewell and Lingering Resonance

After the climax, the caravan moves away again. The Oriental theme fades first, leaving the Russian theme alone to create the afterglow. But now this Russian theme differs from the beginning. It feels deeper and richer through its encounter with Eastern culture.

Finally, only that initial high E remains, disappearing into infinite silence. Yet in our hearts, that beautiful moment when two cultures met and achieved harmony lingers long.

My Personal Listening Method – Ways to Meet This Piece More Deeply

Employ Your Visual Imagination

This work is perfect program music. While listening, try to visualize these scenes in your mind:

– The vastness of endless Central Asian steppes

– The distant sight of a caravan approaching through dust clouds

– Russian soldiers in familiar uniforms and Eastern merchants in colorful attire

– Curious glances toward each other’s cultures

– Moments of heart-to-heart connection despite language differences

Feel the Character Differences Between the Two Themes

The Russian theme is linear and approachable, like a folk song we know well. In contrast, the Oriental theme is curvilinear and mysterious, its ornaments reminiscent of Arabic or Persian pronunciation.

Carefully observe the initial caution when these two themes first meet, and the gradual process of growing intimacy. You’ll sense how natural and beautiful the process of intercultural communication that the music presents truly is.

Notice the Role Distribution Among Instruments

Borodin employed each instrument’s characteristics exquisitely:

– English Horn: The protagonist bearing Oriental colors

– Clarinet and Horn: Voices representing Russian sentiment

– String Pizzicato: The rhythm section expressing caravan movement

– Violin Sustained Notes: The background creating infinite spatial sense

Listen for when each instrument appears and disappears, and how they dialogue with each other—you’ll be amazed by Borodin’s orchestration mastery.

Personal Experience – What This Music Says to Me

When I first heard this piece, I simply thought it was “exotic and pretty” music. But after multiple listenings, I came to realize how many stories are contained within these short seven minutes.

Especially during the section where the two themes meet and create harmony, I always feel moved. The moment when people from completely different cultural backgrounds meet, understand each other, and achieve harmony—this didn’t happen only in 19th-century Central Asia.

It’s happening every day in the multicultural society we live in today. Moments when people who speak different languages, practice different religions, and come from different cultural backgrounds meet, understand each other, and become friends. Borodin’s music seems to have sung the beauty of such moments 150 years in advance.

Practical Tips for Deeper Listening

First Tip: Staged Listening Method

- First Listen: Focus only on the overall atmosphere and story flow

- Second Listen: Try to distinguish between Russian and Oriental themes

- Third Listen: Pay attention to each instrument’s role and orchestration

- Fourth Listen: Center on the climactic section where the two themes meet

Second Tip: Recommended Recordings

- Vladimir Ashkenazy conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra: Balanced interpretation

- Valery Gergiev conducting the Mariinsky Theatre Orchestra: Performance with deep Russian sentiment

- Herbert von Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmonic: Version with excellent orchestral coloring

Third Tip: Complementary Listening

- Rimsky-Korsakov: “Scheherazade”

- Balakirev: “Tamara”

- Tchaikovsky: “1812 Overture”

- Mussorgsky: “Great Gate of Kiev” from “Pictures at an Exhibition”

All these pieces contain “Oriental” colors painted by Russian composers, making comparative listening with Borodin’s work even more fascinating.

A Message Beyond History – Meaning for Us Today

“In the Steppes of Central Asia” is not merely 19th-century Russian music. The message of intercultural understanding and harmony that this work contains feels even more urgent today.

Contemporary society is an era where diverse cultures coexist more than ever before. Yet sometimes differences become sources of conflict. In such times, listen to Borodin’s music. Watch the process where two completely different melodies initially exist independently, gradually approach each other, and finally create beautiful harmony.

Isn’t this the true form of multicultural coexistence? Acknowledging each other’s uniqueness while creating beautiful harmony together.

Next Destination: Arvo Pärt’s Quiet Contemplation

Having witnessed the meeting of two cultures in Borodin’s steppes, it’s time to embark on a completely different dimensional musical journey.

Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s “Spiegel im Spiegel” (Mirror in Mirror) invites us to a world opposite to Borodin’s colorful orchestral palette. Infinite silence and contemplative time created by just two instruments—piano and violin.

After Borodin’s depiction of movement across vast steppes, how about a journey continuing into Pärt’s static meditation? It will become a musical pilgrimage seeking the meaning of true silence in our noisy world.

Next time, let’s explore together the philosophy of minimalism—Pärt’s “music of subtraction.” Experience the deep resonance that music offers when it retains only what is truly necessary, rather than trying to contain everything.