📑 Table of Contents

There’s a particular kind of cold that settles into an English December evening. Not the bitter, biting frost of northern winters, but something gentler—a mist that clings to hedgerows, the distant glow of cottage windows, the faint echo of voices carrying carols across frozen fields.

This is the world Ralph Vaughan Williams captured in his Fantasia on Christmas Carols, and once you hear it, December will never sound quite the same.

The Composer Who Listened to England’s Forgotten Songs

Picture this: It’s 1903, and a well-dressed gentleman in his thirties is walking through the muddy lanes of Essex, knocking on cottage doors. He’s not selling anything. He’s hunting—for songs.

Ralph Vaughan Williams had made a startling discovery. The ancient melodies that English villagers had sung for centuries—passed down through generations like family heirlooms—were disappearing. As railways connected rural communities to cities, as gramophones brought new popular music into homes, the old songs were fading from memory, one elderly singer at a time.

So Vaughan Williams went door to door, notebook in hand, asking farmers and laborers if they remembered any old tunes. When seventy-year-old Charles Pottipher sang him “Bushes and Briars” in a garden in Ingrave, the composer later wrote that it felt like discovering something he had always known but had somehow forgotten.

Over the next decade, he collected over 800 folk songs across 21 English counties. Among them were Christmas carols—not the polished hymns you might hear in grand cathedrals, but rougher, older songs that village wassailers had sung while walking from house to house on winter nights.

Three of these became the heart of his 1912 Fantasia on Christmas Carols.

What Makes This Work So Hauntingly Beautiful

The Fantasia isn’t simply a medley of Christmas tunes stitched together. It’s something far more ambitious: a twelve-minute journey through mystery, celebration, and transcendence, all woven from melodies that ordinary English people had been singing for hundreds of years.

The piece opens with one of the most beautiful moments in all of Christmas music. A solo cello emerges from silence, singing a melody that seems to come from somewhere ancient and half-forgotten. The sound is intimate—like someone humming an old song by firelight, not quite remembering all the words.

This is “The Truth Sent from Above,” a carol Vaughan Williams collected in Herefordshire. Its modal melody (using the Phrygian mode, an ancient scale that sounds neither quite major nor minor) creates an atmosphere of spiritual mystery. The baritone soloist enters, and suddenly the theological weight of the text becomes clear: this isn’t a simple Christmas greeting, but a meditation on creation, fall, and redemption.

Then the mood shifts. We move into “Come All You Worthy Gentlemen,” a Somerset carol with roots in the wassailing tradition. Here’s the communal warmth of Christmas—neighbors gathering, sharing food and drink, celebrating together. The orchestra wakes up. The chorus joins in. You can almost smell mulled cider and see your breath in the cold air.

The final section brings us to the joyful Sussex Carol, “On Christmas Night All Christians Sing.” The music brightens into G major, the full forces unite, and everything builds toward a magnificent climax of praise and wonder. But Vaughan Williams doesn’t leave us in that blaze of glory. Instead, the music gradually fades, the instruments drop away one by one, until we’re left in contemplative stillness—like the last light of a candle flickering into darkness, carrying the memory of warmth.

A Listening Guide: Moments to Treasure

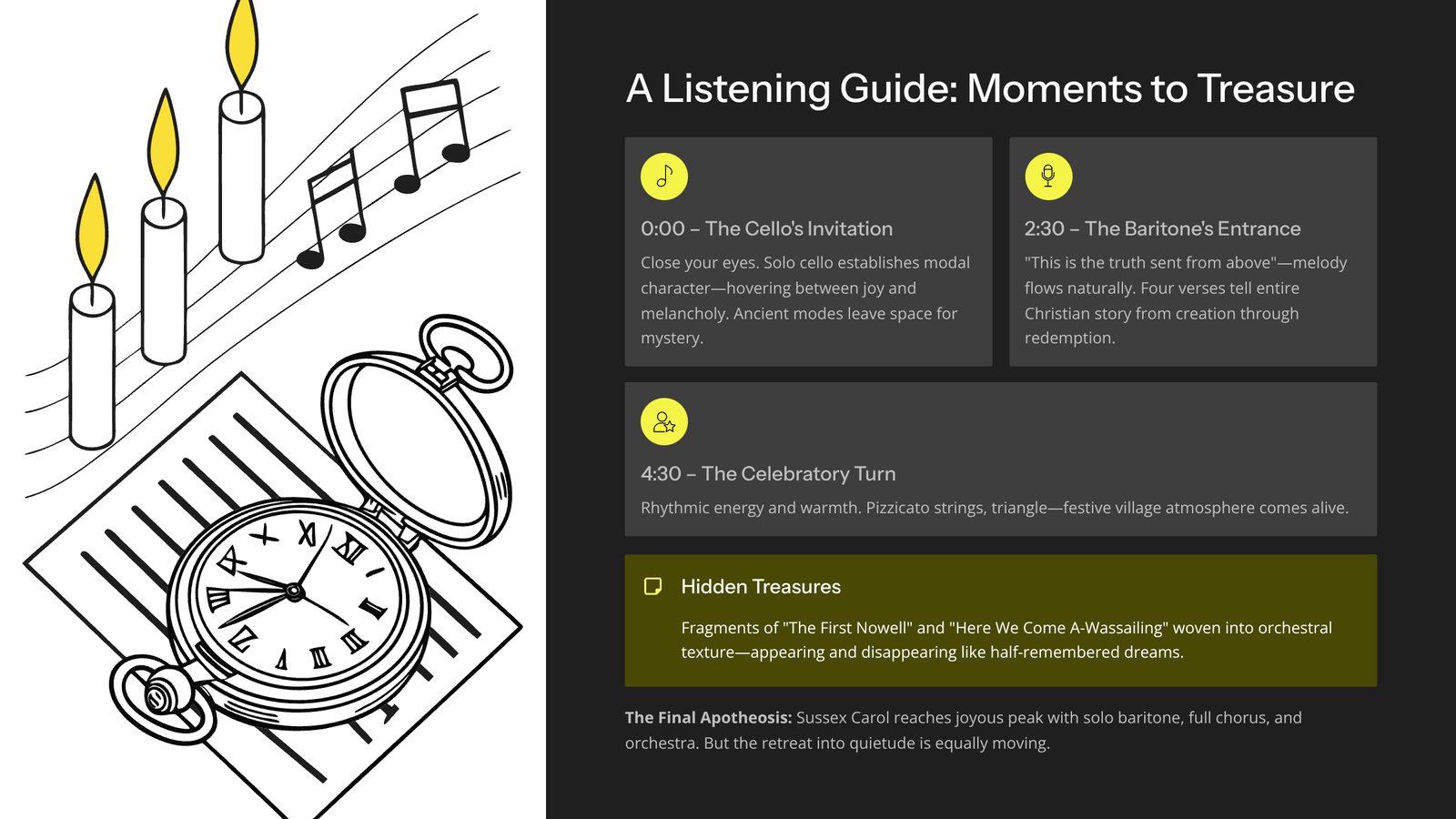

0:00 – The Cello’s Invitation

Close your eyes for this opening. The solo cello melody establishes the modal character of the entire work. Notice how the tune seems to hover between joy and melancholy—this ambiguity is intentional. Ancient modes don’t resolve the way modern major and minor keys do; they leave space for mystery.

Around 2:30 – The Baritone’s Entrance

When the soloist sings “This is the truth sent from above,” listen for how naturally the melody flows. Vaughan Williams preserved the folk song’s simplicity even as he surrounded it with sophisticated orchestration. The text tells the entire Christian story in four verses—from creation through redemption.

Around 4:30 – The Celebratory Turn

The shift to “Come All You Worthy Gentlemen” brings rhythmic energy and warmth. Listen for pizzicato strings (plucked rather than bowed) and the triangle—subtle touches that evoke the festive atmosphere of village celebration.

Hidden Treasures

Vaughan Williams wove fragments of other familiar carols into the orchestral texture. If you catch fleeting echoes of “The First Nowell” or “Here We Come A-Wassailing,” you’re not imagining things. These brief quotations appear and disappear like half-remembered dreams.

The Final Apotheosis

When the Sussex Carol reaches its peak, the combination of solo baritone, full chorus, and orchestra creates one of the most joyous sounds in the Christmas repertoire. But pay special attention to the ending—the way the music retreats into quietude is equally moving.

Why This Music Still Matters

When Vaughan Williams premiered this work at the Three Choirs Festival in September 1912, he was making a statement. At a time when English classical music was still dominated by German Romantic influence, here was something unmistakably, irreducibly English—not through nationalism, but through deep connection to the musical heritage of ordinary people.

The carols he used weren’t composed for cathedral choirs. They were sung by farm laborers and their families, passed down through generations, shaped by countless anonymous voices. By giving them orchestral grandeur without sacrificing their essential simplicity, Vaughan Williams performed an act of cultural preservation and celebration.

Today, when so much of our holiday soundtrack has become commercialized and generic, the Fantasia on Christmas Carols offers something increasingly rare: music that connects us to centuries of human celebration, to the mystery at the heart of midwinter festivals, to the communal warmth that makes the season meaningful.

Recommended Recordings

Cambridge Singers, John Rutter conducting, with Stephen Varcoe (Collegium Records)

This recording is widely praised for its perfect balance between soloist, choir, and orchestra. Rutter’s conducting feels natural and flowing, never forced. An excellent first choice.

Corydon Singers, Matthew Best conducting (Hyperion Records)

A slightly more dramatic interpretation with crisp choral work. Some listeners prefer its more defined sonic picture.

Richard Hickox with the London Symphony Orchestra (Chandos)

Hickox brings a grander, more symphonic approach that emphasizes the orchestral colors. Beautiful, though it loses some of the folk music intimacy.

A Historical Curiosity

In 1943, Leopold Stokowski conducted a purely orchestral arrangement with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, replacing the baritone solo with cor anglais. This recording survives and offers a fascinating alternative perspective, though the version with voice remains definitive.

Before You Press Play

Find twelve uninterrupted minutes. The Fantasia isn’t background music—it rewards your full attention.

If possible, listen in the evening. There’s something about this music that belongs to candlelight and winter darkness.

Don’t worry about following every detail on your first listen. Let the music wash over you. The modal harmonies, the shifting textures, the gradual journey from mystery through celebration to peace—these elements work on you even if you can’t name them.

And perhaps, as the final notes fade, you’ll understand why Vaughan Williams spent years walking through English villages, collecting songs from elderly singers. He wasn’t just preserving folk melodies. He was saving something essential about what it means to celebrate together in the darkest time of year—and then giving it back to us, transformed into art.

The Fantasia on Christmas Carols was first performed on September 12, 1912, at Hereford Cathedral, with the composer conducting. It remains one of the most beloved works in the English choral repertoire, a testament to both Vaughan Williams’ genius and the anonymous folk singers whose melodies he immortalized.