Table of Contents

A Soul Reaching Through Darkness

Some music poses questions the moment you hear it. “Who am I? What do I want?”—questions too vast to answer, too urgent to ignore. When I first heard Liszt’s ‘Vallée d’Obermann,’ I encountered the voice of a soul writhing on the piano keys.

From the very first note, the heart grows heavy. A low, somber melody in E minor descends slowly, and above it, three notes drop like empty space. It’s as if someone reaches out through darkness, grasping at nothing. This is not a portrait of beautiful Swiss landscapes. This is the monochord of human suffering, a record of Romanticism’s most desperate inquiry.

Liszt attached literary references to this music. Senancour’s novel Obermann—a confessional epistolary work about a young recluse who isolates himself in the Alps. And a passage from Byron’s poetry: “Could I embody and unbosom now / That which is most within me… But as it is, I live and die unheard, / With a most voiceless thought.”

Every time I listen to this piece, I witness an artist’s desperate gesture to express the inexpressible.

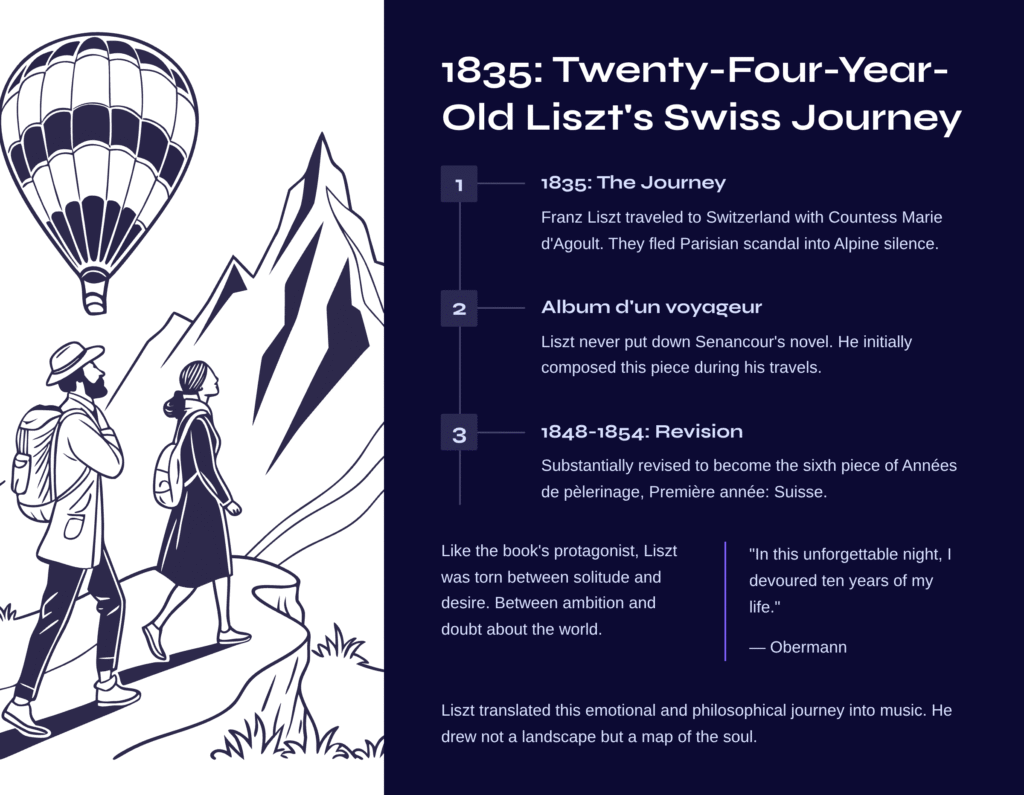

1835: Twenty-Four-Year-Old Liszt’s Swiss Journey

Franz Liszt traveled to Switzerland with his lover, Countess Marie d’Agoult, in 1835 when he was merely 24 years old. Marie was pregnant with their first child, and the couple fled Parisian society’s scandal into the Alpine silence.

During that journey, Liszt reportedly never put down Senancour’s novel Obermann. Like the book’s protagonist, Liszt himself was torn between a young genius’s solitude and desire, between ambition and doubt about the world. He initially composed this piece under the title Album d’un voyageur, then substantially revised it between 1848 and 1854 to become the sixth piece of Années de pèlerinage, Première année: Suisse.

The novel’s Obermann asks: “All causes are hidden, all ends are deceptive, all forms are mutable… I am merely prey to unconquerable desire, bewitched by a false world’s illusions.” And after experiencing absolute powerlessness before nature’s vastness one night, he confesses: “In this unforgettable night, I devoured ten years of my life.”

Liszt translated precisely this emotional and philosophical journey into music. He drew not a landscape but a map of the soul.

The Magic of One Theme Transforming into Three Faces

The key to understanding this piece is simple. Liszt constructs the entire nine minutes from a single musical theme. The low, somber melody that appears first—the left hand’s descending line and the right hand’s three empty notes—this is everything. Yet this theme continuously transforms and reinterprets itself throughout the piece, evoking completely different emotions.

First Face: Meditation on Solitude

The piece begins in E minor darkness. The left hand descends heavily, while the right hand drops three lonely notes in the upper register. Such emptiness in this moment. It’s like someone standing alone in vast mountains, crying out toward a cliff where no echo returns.

The music flows slowly, the same theme repeating but gradually intensifying. It feels like despair ripening. Liszt depicts here “Obermann’s infinite solitude.”

Second Face: Leap Toward Light

But suddenly, the music changes. The same theme now appears in C major’s bright light. The moment E minor’s despair transforms into C major’s jubilation, my breath stops every time.

This isn’t a simple modulation. It’s the moment when Obermann feels—for an instant, truly an instant—spiritual liberation in nature. The music grows brighter, more intense, ascending as if climbing toward a mountain peak. That the same melody can contain such different emotions—this is Liszt’s genius.

Third Face: Fragments of Nightmare

But liberation doesn’t last. The music becomes violent again, this time brutally distorted. Chromatic progressions pour forth, dissonances grate. Rapid glissandi and fierce scales sweep across the keyboard, and Liszt instructs in the score: “recitativo”—play as if singing, as if crying out.

This is Obermann’s nightmare. That night in the novel, when he experienced “inexpressible feelings” and “absolute helplessness before nature’s immensity.” The music shatters, twists, screams. Listening, one’s chest tightens.

Coda: Victory or Illusion?

Finally, the music rises to a majestic climax. All transformations converge in a single moment, seemingly proclaiming sublime victory. But Liszt doesn’t end there. The final measures waver unstably, asking us: “Is all this real? Or is it illusion?”

A scholar once said: “The music reaches a moment of rapture, but the final moments force us to recognize that all this achievement is illusion.” Here lies Romanticism’s tragedy. The pursuit of the absolute, yet the realization that everything might ultimately be meaningless.

What I Discovered in This Music

Every time I listen to this piece, I meet the Obermann within myself. Don’t we all have unanswerable questions? “Do I really know what I want? Is what I pursue real or illusion?”

Liszt doesn’t answer these questions. Instead, he captures in music the weight of the questions themselves, their urgency, their beauty. This journey flowing from darkness to light, then back to confusion, isn’t mere emotional fluctuation. This is the very way humans live.

After hearing it the first time, I couldn’t forget for days that final chord’s instability. Sounding like victory yet lacking conviction, seeming like ecstasy yet somehow hollow. That is precisely Obermann, and Liszt, and perhaps all of us.

Three Ways to Listen More Deeply

1. First Listen: Follow Only the Emotional Arc

Forget difficult analysis. Feel just three things.

– The opening’s heavy, sorrowful atmosphere → “Why such solitude?”

– The middle’s sudden jubilation → “Wait, it brightened! Liberation!”

– The ending’s violence and instability → “Chaos again… and an answerless conclusion”

2. Second Listen: Catch the Same Melody Transforming

Remember the low theme that appeared first. It keeps appearing but sounds completely different.

– First: somber and heavy

– Middle: bright and jubilant

– End: violent and shattering

That Liszt can paint such different worlds with the same melody—this is his mastery.

3. Third Listen: Remember Obermann’s Questions

Listen while recalling the novel’s Obermann’s questions: “What do I want? Who am I?” That the music doesn’t give clear answers to these questions—this itself is Romanticism’s truth.

Recommended recordings include Alfred Brendel’s 1970s interpretation or Vladimir Horowitz’s 1953 version. Brendel offers philosophical maturity, while Horowitz balances technical brilliance with dramatic emotion.

At Anguish’s End, Dreaming of Flight

Liszt’s Obermann poses questions, anguishes, glimpses light briefly, but ultimately arrives at uncertainty. You may be exhausted from following this Romantic soul’s heavy journey.

Then perhaps it’s time to pose a different question: “What if one could completely cast off anguish, defy gravity, and soar into pure light?”

Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 4, second movement ‘Prestissimo volando’ captures precisely that moment. If Liszt questioned in darkness, Scriabin proposes ecstatic flight that needs no questions.

‘Volando’—flying, soaring. This single performance instruction says everything. Notes flying across the keyboard, melodies losing weight, mystical rapture. Scriabin chose spiritual transcendence over Liszt’s philosophical struggles.

If you’ve anguished enough in Obermann’s valley, prepare to soar skyward with Scriabin. Only those who’ve passed through darkness can truly understand light’s flight.