Table of Contents

Taking Flight at the Edge of Longing

Have you ever desired something so intensely that the longing itself dissolved, transforming into something entirely different? When I first heard the second movement of Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 4, I thought of such moments.

The final note of the slow, contemplative first movement still trembles in the air when suddenly—truly suddenly—rapid notes cascade across the keyboard, ascending. It’s as if someone standing firmly on the ground suddenly forgets gravity and rises into the sky. Scriabin titled this second movement “Prestissimo volando”—”as fast as flight itself.”

It’s brief. Barely two minutes. Yet within that compressed span unfolds a musical experience like a metamorphosis of the soul, leaping from starlight to sun, from desire to divinity. This essay is a small invitation to witness that moment of transformation together.

Scriabin the Mystic, and the Record of 1903

Alexander Scriabin (1870-1915) was among the most singular composers Russia ever produced. Though he inherited Chopin’s lyricism, he didn’t stop at writing beautiful melodies. Scriabin was a mystic who sought cosmic union through music, composing each piano work as if documenting a spiritual journey.

Piano Sonata No. 4, Op. 30 was composed in 1903 and published in 1904. It stands at the threshold between Scriabin’s early Romantic style and his middle-period mystical language. He attached his own poem to this work:

“A distant star calls to me. A piece of my heart flies toward that star…

A maddened dance, divine play! O radiant, ecstatic one!

I fly toward you. I become the sun and swallow its light!”

This poem corresponds precisely to the music’s structure: the first movement as “desire and meditation,” the second as “flight and divine union.” Scriabin believed music was not mere arrangement of sounds but incantation capable of altering consciousness itself. To listen to his piano sonatas, then, is not simply to appreciate beautiful melodies but to participate in the journey of spiritual experience the composer designed.

This work ranks among Scriabin’s shortest sonatas. Total performance time: about 8 minutes. It comprises only two movements—the first (Andante) and second (Prestissimo volando)—played without pause between them. That he compressed such cosmic drama into so brief a span is astonishing.

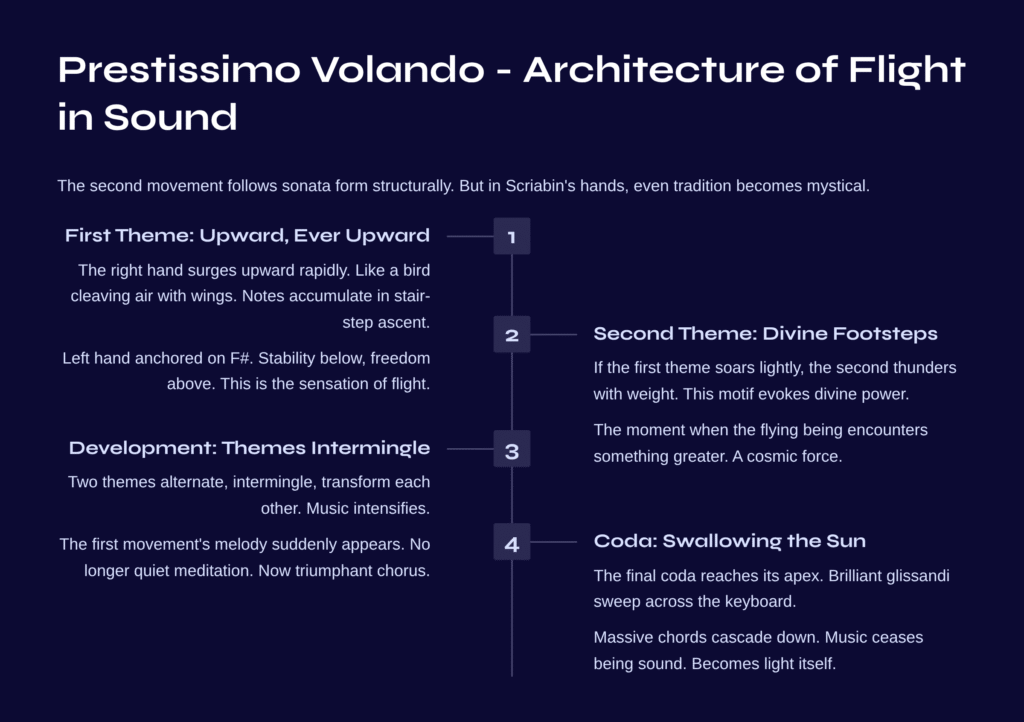

Prestissimo Volando – Architecture of Flight in Sound

The second movement, Prestissimo volando, follows sonata form structurally. But in Scriabin’s hands, even traditional sonata form becomes something mystical.

First Theme: Upward, Ever Upward

The moment the music begins, the right hand surges upward rapidly. Like a bird cleaving the air with its wings, notes accumulate in stair-step ascent. The left hand remains anchored on F#, creating a curious contrast—stability below, freedom above. This is the “sensation of flight.”

Here Scriabin uses intervals of fourths and fifths instead of traditional tertian harmony. The result sounds bright yet unstable, mysterious yet powerful. It’s the kind of floating sensation you might hear if you stood suspended in air rather than planted on solid ground.

Second Theme: Heavy Authority Like Divine Footsteps

If the first theme soars lightly, the second theme thunders with weight. This motif, resonating from the low bass, evokes nearly “divine power.” It’s the moment when the flying being encounters something greater—a cosmic force.

These two themes alternate, intermingle, and transform each other as the music intensifies. The lyrical melody from the first movement suddenly appears midway through, but it’s no longer quiet meditation. Now that melody rings out like a triumphant chorus of victory.

Coda: The Moment of Swallowing the Sun

The final coda reaches its apex. Brilliant glissandi sweep across the entire keyboard while massive, body-shaking chords cascade down. This is precisely the moment Scriabin described in his poem: “I become the sun and swallow its light.” Music seems to cease being sound and becomes light itself. In that light, everything melts into oneness.

What I Encountered in This Music

When I first heard this piece, I realized music could be this physical. Scriabin’s second movement isn’t merely heard with the ears—it’s music felt in the body. Notes pouring forth in rapid tempo push against me like wind and rain; heavy chords press down on my chest.

On some days, this music sounded like liberation. The sensation of suddenly being released from restraints. On other days, it sounded like fear. Am I rising too quickly? Will I fall? Yet strangely, even that fear transforms into ecstasy. Scriabin seemed to know that anxiety and rapture spring from the same root.

In the moment of transition from the slow meditation of the first movement to the flight of the second, I always hold my breath. The shift is so abrupt that the world seems to pause for an instant. And when the music resumes, I’m already standing somewhere else.

Each time I hear this piece, I think: perhaps happiness lies not in fulfilling desire but in desire’s transformation. Scriabin’s second movement isn’t a story of desire’s fulfillment but of desire’s complete metamorphosis into something else entirely—flight, light, divinity. This music is not a song of lack but a song of transcendence.

A Guide to Deeper Listening

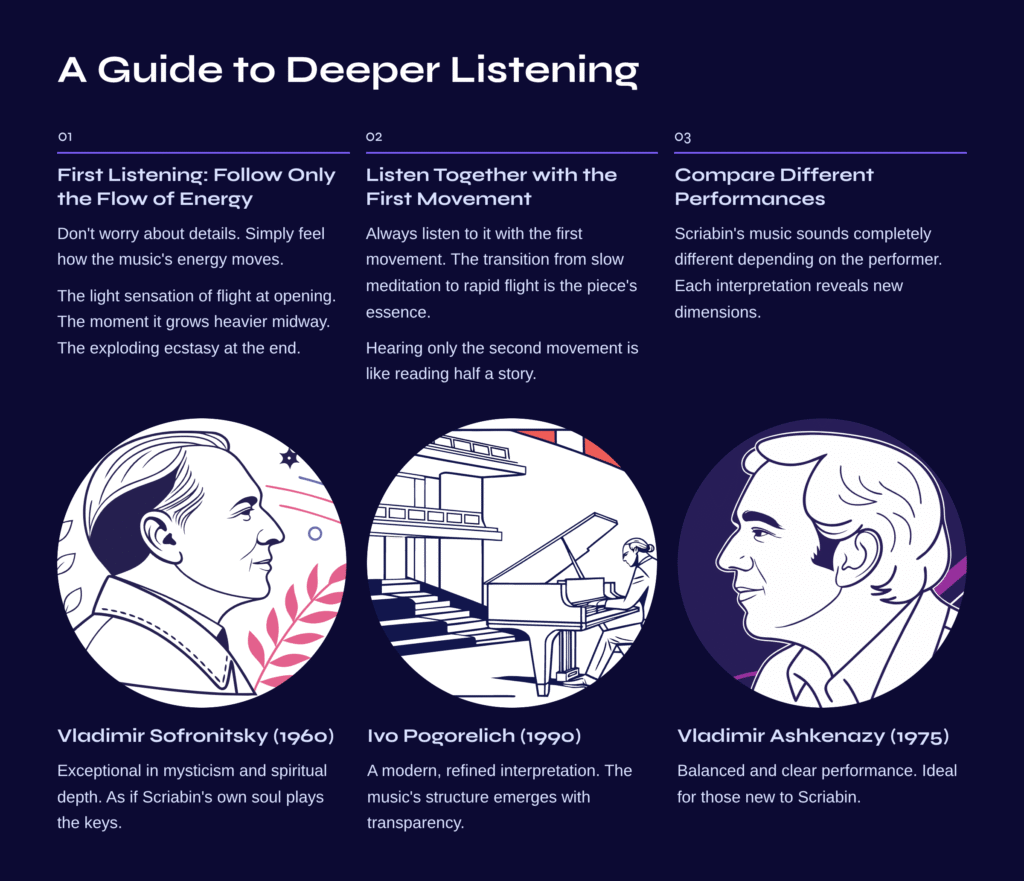

1. First Listening: Follow Only the Flow of Energy

When you first hear this piece, don’t worry about details. Simply feel how the music’s energy moves. The light sensation of flight at the opening, the moment it grows heavier midway through, and the exploding ecstasy at the end. Grasping these three large movements is sufficient.

2. Listen Together with the First Movement

Rather than hearing the second movement in isolation, always listen to it with the first movement. The transition from slow meditation to rapid flight is the piece’s essence. Hearing only the second movement without the first is like reading half a story.

3. Compare Different Performances

Scriabin’s music sounds completely different depending on the performer. Recommended recordings:

- Vladimir Sofronitsky (1960): Exceptional in mysticism and spiritual depth. It’s as if Scriabin’s own soul plays the keys.

- Ivo Pogorelich (1990): A modern, refined interpretation. The music’s structure emerges with transparency.

- Vladimir Ashkenazy (1975): Balanced and clear performance. Ideal for those new to Scriabin.

Though it’s the same piece, Sofronitsky’s performance sounds dark and weighty while Pogorelich’s is bright and lucid. Sensing these differences is one of classical music’s great pleasures.

The Flight Never Ends

Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 4, second movement is short. Yet within that brief span, we witness the complete trajectory of a soul ascending from earth to heaven, from desire to divinity.

When this music ends, you’ll be sitting alone in a quiet room. But something will have changed. As if someone lightly touched your shoulder, as if some small weight lifted from your body. Scriabin wrote such music. Music that makes the world look slightly different after you’ve heard it.

Flying toward starlight must feel something like this. Feet leaving the ground, air enveloping the body, finally becoming one with light. In those two minutes, Scriabin offers us that experience as a gift.

When you listen to this music, I hope you, too, will take flight.