Table of Contents

The First Song Beneath the Starlit Sky

Is there any music that touches the deepest recesses of the human heart quite like a mother’s lullaby? The moment we first hear Frédéric Chopin’s Berceuse in D-flat major, Op. 57, completed in 1844, we find ourselves transported back through time to the memories of childhood. This work, where dreamlike variations bloom one by one above the simple melody of a gently rocking cradle, leads us into an entirely different world in just over four minutes.

We soon understand why Chopin first titled this piece “Variantes” before changing it to “Berceuse” (lullaby). This is not merely a set of variations, but a poem that paints a child’s dreams in music. Through this composition, we experience those moments when a mother’s storytelling voice transforms into increasingly fantastical and beautiful forms within the child’s dreams.

A New Language Born from Fifteen Years of Confession

A Completely New Chopin Emerging from Silence

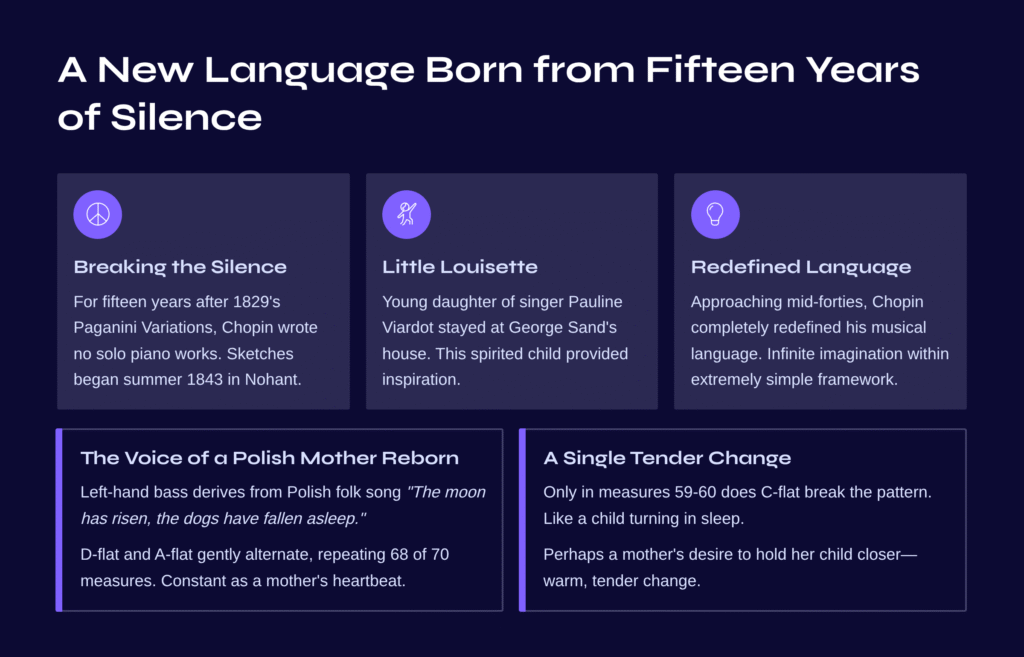

For fifteen years after the Paganini Variations of 1829, Chopin wrote no solo piano works. Breaking this long silence, sketches for this lullaby began in the summer of 1843 while staying with George Sand in Nohant. At the time, little Louisette, the young daughter of singer Pauline Viardot, was staying at Sand’s house, and many believe this spirited child provided Chopin with inspiration.

However, the true significance of this work lies beyond simple inspiration. This was the moment when Chopin, approaching his mid-forties, completely redefined his musical language. No longer competing with flashy virtuosity or grand structures, he discovered a way to unfold infinite imagination within an extremely simple framework.

The Voice of a Polish Mother Reborn

The left-hand bass of this lullaby derives from the Polish folk song “The moon has risen, the dogs have fallen asleep” that Chopin heard from his mother in childhood. This pattern of D-flat (tonic) and A-flat (dominant) gently alternating repeats 68 times out of the total 70 measures, creating a rhythm as constant and stable as a mother’s heartbeat.

Only once, in measures 59-60, does a C-flat note receive expressive emphasis, breaking this pattern. It feels like a child turning slightly in their sleep, or perhaps a mother’s desire to hold her child even closer—a warm, tender change.

The Magic of Infinite Variation Hidden in Simplicity

An Entire Universe Born from a Single Measure

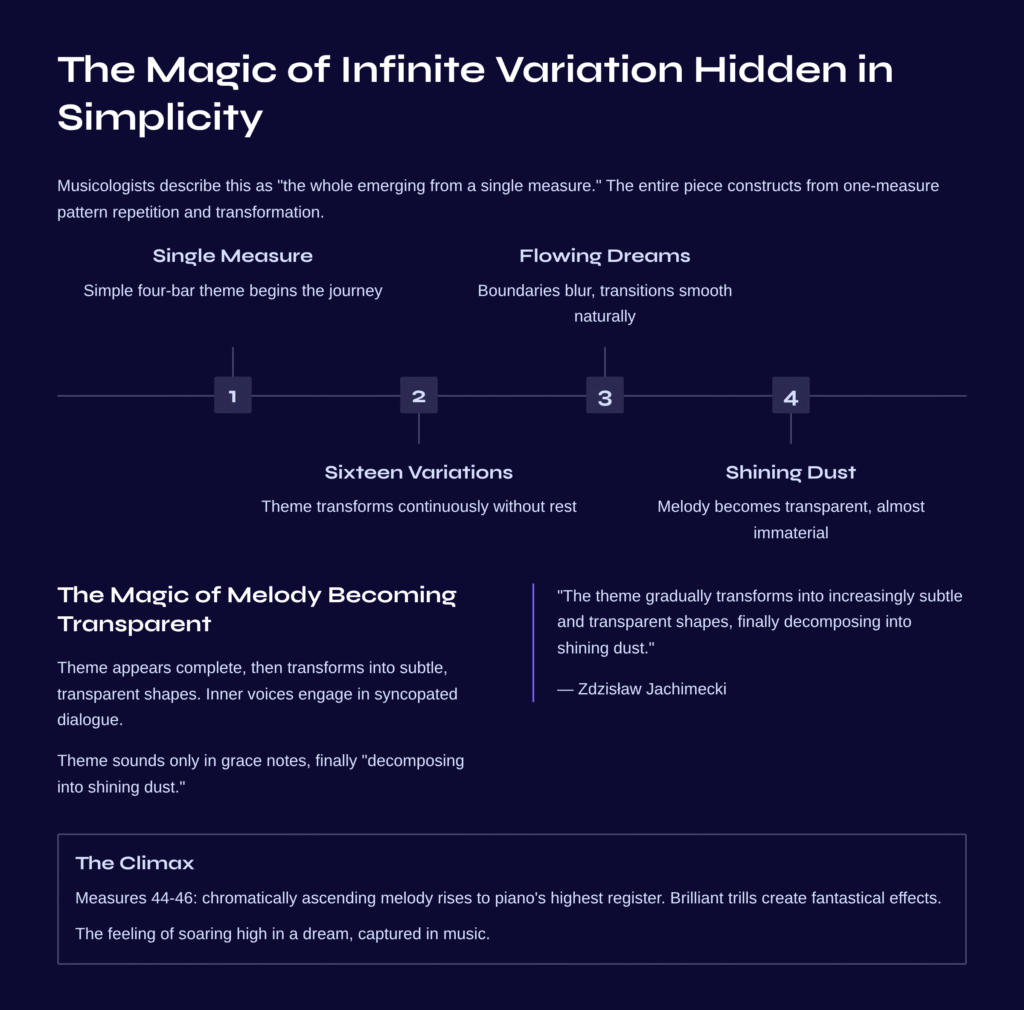

There’s a reason musicologists describe this work as “the whole emerging from a single measure.” Rather than the conventional eight-bar structure, the entire piece is constructed from the repetition and transformation of a single-measure pattern. Like ripples from a single drop of water creating increasingly large and complex circles, a simple four-bar theme transforms into sixteen different variations.

Yet these variations flow in continuous streams without rest, unbroken by commas. Like one dream naturally flowing into the next, the boundaries are blurred and the transitions smooth—one of this work’s greatest charms.

The Magic of Melody Becoming Increasingly Transparent

As musicologist Zdzisław Jachimecki beautifully described, the theme in this piece first appears in complete form, then gradually transforms into increasingly subtle and transparent shapes. The inner voices engage in syncopated dialogue with the theme, then the theme sounds only in grace notes, finally “decomposing into shining dust” to become almost immaterial.

The climax in measures 44-46 is particularly striking, where a chromatically ascending melody rises to the piano’s highest register, creating fantastical effects through a series of brilliant trills. It’s as if the feeling of soaring high in a dream has been captured in music.

A Journey of Dreams Painted in Sound

First Listening: Following the Cradle’s Gentle Sway

When first hearing this piece, don’t approach it analytically. Simply sit quietly and surrender to the gentle rocking of the left hand. Naturally follow how the right-hand melody transforms like a dream above the stability created by the constant D-flat to A-flat pattern.

When the quiet two-measure introduction passes and the right hand sings the lyrical four-bar theme dolce (sweetly), you’ll feel the warmth of a mother lovingly singing the first verse to her child.

Second Listening: Exploring the Evolution of Variations

On the second hearing, observe how each variation becomes gradually more complex and ornate than the last. The process by which an initially simple melody becomes filled with faster passages, delicate trills, and arabesque-like ornaments feels like a child’s dreams becoming increasingly fantastical.

Particularly in the middle section (measures 19-46), you’ll experience a mysterious atmosphere like “bright dreams flickering in a half-sleeping state.”

Third Listening: Discovering the Ancestor of Jazz

Remarkably, this Chopin lullaby possesses characteristics that seem to anticipate jazz improvisation that would emerge a century later. The method of freely creating variations using only two chords (D-flat and A-flat) is strikingly similar to the modal jazz of Keith Jarrett or Bill Evans.

Listen to Bill Evans’ “Peace Piece” (1958), then return to this lullaby. You’ll discover the same spirit, the same freedom, connected across a hundred-year gap.

The Diverse Dream Worlds Revealed by Performers

Arthur Rubinstein: The Warmest Mother’s Embrace

Rubinstein’s 1958 recording is the performance I most recommend to those encountering this piece for the first time. With elegant phrasing and expression that is both natural and refined, there’s a warmth like an experienced mother singing a lullaby to her child. You can feel Rubinstein’s unique sensitivity in how he proceeds at a brisk tempo while naturally adjusting the pace where needed.

Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli: An Impressionist Painter’s Brushstrokes

Michelangeli’s performance is famous for its most Debussy-like interpretation. With an almost constant quick tempo, incredibly light touch, and luminous tone colors that emphasize the upper voices, he highlights each variation’s character through subtle tonal changes, like an Impressionist painter capturing shifting light on canvas.

Vladimir Ashkenazy: A Meditating Mother’s Heart

Ashkenazy’s performance offers the slowest, most meditative interpretation. Listening to his reverent and tranquil playing feels like glimpsing into the heart of a mother caring for her child alone in a quiet room at night. His particularly quiet treatment of the left hand and remarkably steady tempo maintenance even in the most elaborate passages is impressive.

A Musical Language That Transcends Time

Chopin’s Berceuse Op. 57 appears to be a simple four-minute miniature, yet it contains the most beautiful emotions humans have created, compressed within. The love between mother and child, the boundary between dream and reality, the exquisite balance of simplicity and complexity, and above all, the magic of music that transcends time—all of these are dissolved within this work.

Though more than 150 years have passed, when we listen to this music we still return to the warm memories of childhood. Like a lullaby that continues to resonate even after the child has fallen asleep, the lingering resonance that remains in our hearts long after the performance ends—this is the true power of this work.

The combination of extreme structural minimalism with textural maximalism, the infinite imagination unfolding over simple harmonic progressions, was a revolutionary experiment that anticipated Debussy and Ravel’s Impressionism, Satie’s “Gymnopédies,” and even 20th-century minimalism and modal jazz.

The story that cradle dreams tell never ends. Each time we listen, we discover new variations, new dreams, new stories.

Next Destination: The Secret Inner World of Brahms’ Intermezzo Op. 76 No. 7

If you’ve sufficiently immersed yourself in Chopin’s dreamlike lullaby, how about embarking on an intimate musical journey of completely different character? Brahms’ Intermezzo Op. 76 No. 7 in A minor possesses charms diametrically opposite to Chopin’s lullaby.

If Chopin’s Berceuse is a song of warm, protected love heard from above the cradle, Brahms’ Intermezzo is an inner confession whispered like writing in a diary in one’s private room. Hidden beneath the surface’s beautiful melody lies another melody, like the heart of someone living with unspeakable emotions held deep within their chest.

During 3 minutes and 45 seconds, Brahms guides us ever deeper into the inner self. Where Chopin showed the evolution of dreams through sixteen variations, Brahms reveals the depth of hidden emotions through the true melody concealed in the inner voices. Like Chopin returning to the piano after fifteen years of silence, Brahms too embedded in these miniatures a new mode of expression discovered after a long hiatus.

From external brilliance to internal depth, from the world of dreams to real-world contemplation. Experiencing these two works in succession will allow you to appreciate how broad and deep the emotional spectrum of 19th-century Romantic piano music can be.