Table of Contents

When a Boy of Nineteen Touched Eternity

Imagine being nineteen years old, sitting at your desk with ink-stained fingers, knowing that the piece you’re writing will determine whether you graduate. The pressure alone would crush most of us. But Gabriel Fauré wasn’t writing just to pass an exam. He was writing to capture something he’d heard in the silence between prayers—a sound that shimmered like light through stained glass, that moved like breath across water.

The year was 1865. Paris hummed with the aftermath of revolution, and the young Fauré sat in the École Niedermeyer, crafting what would become the Cantique de Jean Racine, Op. 11. His teacher, the legendary Camille Saint-Saëns, was on the jury. They expected Latin. They expected tradition. What they received instead was a French prayer so achingly beautiful that it won first prize and, more than a century later, still stops time whenever it’s sung.

This wasn’t just a graduation piece. It was the moment a boy became a voice for something eternal.

The Prayer That Traveled Through Centuries

Here’s what moves me most about this work: it’s a prayer passed through hands across time like a sacred flame. The original Latin hymn, Consors paterni luminis (“Light of Light”), was written in the 4th century by Saint Ambrose of Milan. Can you imagine? In the year 340, when the Roman Empire still stood, a bishop penned words about divine light piercing darkness.

Then, thirteen centuries later, the French playwright Jean Racine—yes, the same Racine who gave us Phèdre and Andromaque—took those ancient Latin verses and transformed them into French poetry. He kept the spiritual core but dressed it in the elegant language of 17th-century France. The prayer became not just a translation but a conversation between eras.

And finally, in 1865, a nineteen-year-old music student named Gabriel Fauré gave these words their wings. He set Racine’s French text to music that feels both ancient and impossibly modern, creating something that belongs to no single century but to all of them.

Think about that journey: from 4th-century Latin to 17th-century French to 19th-century music. Cantique de Jean Racine is a relay race across fourteen hundred years, and each runner carried the same torch—the longing for light in darkness, for grace in our mortal confusion.

The Sound of Breaking Silence

The opening is deceptive in its simplicity. The organ begins alone, or sometimes strings and harp in modern arrangements, with a flowing triplet pattern that never stops throughout the entire piece. It’s like the pulse of prayer itself, continuous and gentle. Then the voices enter—not all at once, but one by one, like candles being lit in a dark chapel.

Bass voices first, then tenors, then altos, finally sopranos. Each part carries the same melody but enters at different times, creating what musicians call a canon. You might know this technique from “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” but here it becomes something transcendent. It’s as if each voice is a soul joining the prayer, layer upon layer, until the sound becomes thick with devotion.

The text they sing speaks of breaking “the silence of the peaceful night.” That’s exactly what the music does—it doesn’t shatter the quiet, it illuminates it. Like dawn gradually revealing a landscape you didn’t know was there.

Fauré composed this in D-flat major, a key that has its own luminous quality. The tempo marking is Andante (walking pace) with the instruction cantabile—”songlike.” But listen closely, and you’ll hear that Fauré’s genius lies not in complexity but in restraint. Where other nineteen-year-olds might have tried to impress with flashy passages, Fauré understood that the divine doesn’t shout. It whispers. And if you’re quiet enough, you hear everything.

The Architecture of Longing

The piece follows a classical ABA structure, but Fauré treats this framework like a poet treats a sonnet—the form is there to give shape to emotion, not to constrain it. The A section establishes our prayer, grounded and steady. Each vocal part enters with measured reverence, building that canonic texture that feels like souls gathering.

Then comes the B section, and everything shifts. The key modulates to B-flat minor—a darker, more urgent color. The text at this moment speaks of divine fire: “Pour forth the strong fire of your grace upon us.” And Fauré responds by lifting the music higher, creating the emotional peak of the entire work. The voices climb, the harmonies grow richer, the intensity builds. You can feel the prayer becoming more desperate, more necessary.

But here’s what I find remarkable: even at this climax, Fauré never loses his composure. He never lets the music become hysterical or overwrought. It’s passionate, yes, but with the passion of someone who has truly experienced the sacred—not as spectacle, but as intimate encounter.

Then the A section returns, but transformed. It’s like returning home after a long journey and seeing your house with new eyes. The melody is the same, yet everything has deepened. The voices move together now, no longer in canon but in hymn-like chords, and gradually the music settles into silence like dust motes finally coming to rest.

The entire journey—from awakening to crisis to resolution—takes about five minutes. But those five minutes contain a lifetime of feeling.

What the Words Actually Mean

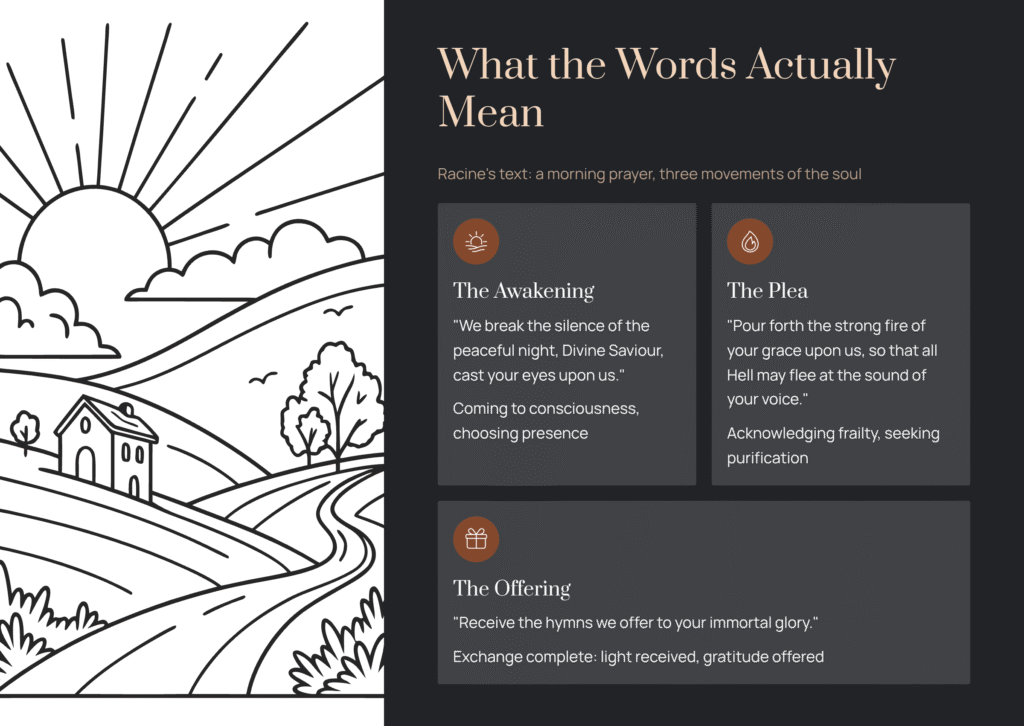

Even if you don’t speak French, knowing what’s being sung changes how you hear the music. Racine’s text is a morning prayer divided into three movements of the soul:

The Awakening: “We break the silence of the peaceful night, Divine Savior, cast your eyes upon us.” It’s the moment of coming to consciousness, of choosing to face another day not alone but in the presence of something greater.

The Plea: “Pour forth the strong fire of your grace upon us, so that all Hell may flee at the sound of your voice.” This is where the music intensifies, where we acknowledge our frailty and our need for something beyond ourselves. The “fire of grace”—what a phrase. Not a gentle glow but a strong fire, something purifying and fierce.

The Offering: “Receive the hymns we offer to your immortal glory.” By the end, the prayer has become an exchange. We’ve asked for light and grace; now we offer back our song, our gratitude, our continued attempt to live in that light.

Fauré understood that these weren’t just pretty words. They were a map of the spiritual life: awakening, struggle, surrender, offering. And he gave each stage its own musical color, its own emotional weight.

How to Let This Music Move Through You

Here’s what I suggest when you listen:

First, do nothing. Don’t analyze, don’t count sections, don’t try to identify the key changes. Just sit somewhere comfortable, close your eyes if you want, and let the sound wash over you. Notice where your breath naturally slows. Notice which moments make your chest feel open.

On the second listening, pay attention to the voices. Can you hear how they enter one at a time at the beginning? Try following just one voice—perhaps the soprano line—all the way through. Then listen again and follow a different part. You’ll discover that each voice has its own journey, its own melodic arc, yet they all interweave perfectly.

For the third listening, focus on the moment around 2:30-3:00 (timing varies by performance, but it’s the middle section). This is where the key changes, where the text speaks of divine fire, where Fauré lets the intensity build. What happens to your body during this passage? Do you feel tension, release, longing?

Finally, listen with the text in front of you. You can find English translations easily online. Read along and notice how perfectly Fauré matches music to meaning—how the words “jour éternel” (eternal day) receive these radiant, sustained notes, how “fuis à ta voix” (flees at your voice) gets this decisive, descending motion.

Some recommended recordings to explore:

- John Rutter and the Cambridge Singers offer crystalline clarity and spiritual purity. The sound is almost transparent, which lets you hear every inner voice.

- VOCES8 with the English Chamber Orchestra (2023 recording) brings a more contemporary warmth, with strings and harp creating an almost otherworldly atmosphere.

- The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge under Stephen Cleobury delivers the traditional Anglican cathedral sound—rich, reverberant, steeped in centuries of sacred music tradition.

Each interpretation reveals different facets of the work. None is “correct”—they’re different windows into the same cathedral.

The Echo of the Requiem

If you know Fauré’s later masterpiece, the Requiem Op. 48, you’ll hear echoes of that work already present in this student composition. The same restraint, the same preference for consolation over drama, the same ability to speak of death and divinity without ever raising his voice.

Many commentators note that Cantique de Jean Racine and the Requiem are often performed together, like twin pillars of Fauré’s spiritual vision. One is a prayer for the living, asking for grace to face each new day. The other is a prayer for the dead, offering them peace. Together, they bookend human existence with music that says: you are held, you are known, you do not go into darkness alone.

What moves me is that Fauré was only nineteen when he wrote the Cantique, but he already possessed that mature wisdom, that understanding that the sacred doesn’t need to be loud to be powerful. Most teenagers are discovering their voice by shouting. Fauré discovered his by listening to silence.

Why This Music Endures

There’s a reason the Cantique de Jean Racine has become a staple of choral repertoire worldwide. It’s not just that it’s beautiful—though it is, achingly so. It’s that the piece fulfills a need we didn’t know we had.

In our accelerated, fractured age, where silence has become rare and attention is currency, this five-minute work offers something radical: it asks you to slow down. To breathe. To hear voices moving together not in competition but in harmony. To consider that maybe, just maybe, there are things beyond our immediate concerns that deserve our attention.

You don’t have to be religious to be moved by this music. You don’t have to believe in the specific theology of Racine’s text. What you need is the willingness to be still, to listen, and to let something reach you that doesn’t demand anything except your presence.

When I listen to Cantique de Jean Racine, I think about that nineteen-year-old boy in Paris, writing by lamplight, probably worried about passing his exam, probably wondering if his music would mean anything to anyone. He couldn’t have known that more than 150 years later, his graduation piece would be sung in cathedrals and concert halls around the world, that it would bring tears to people who didn’t speak his language, that it would become a prayer not just for Christians but for anyone seeking light in darkness.

That’s what great music does. It outlasts its creator’s intentions. It becomes a vessel that each generation fills with their own longing, their own hope, their own need for something beyond the daily grind of existence.

So I invite you: take five minutes. Find a recording. Sit somewhere you won’t be disturbed. And listen to what a nineteen-year-old boy heard in 1865—that sound between notes, that light between words, that grace that has no name but somehow, impossibly, has this music.

The silence is waiting to be broken. All you have to do is press play.