Table of Contents

Do you believe in conversations that happen without words? Not the awkward silences or meaningful glances we exchange with strangers on the subway, but real conversations—the kind where two completely different souls meet and somehow understand each other perfectly.

Bach believed in them. And in 1734, he wrote one into existence.

The Mystery Begins with an Unusual Choice

Here’s what makes the Sinfonia from Bach’s Christmas Oratorio Part II so unusual: it’s the only movement in the entire six-part work that begins with instruments alone. No voices. No text. Just seven minutes of pure instrumental dialogue that somehow tells the story of the most pivotal moment in Christian theology—the meeting between celestial messengers and earthbound shepherds.

Why would Bach do this? Why silence the human voice at the precise moment when the gospel narrative becomes most dramatic? When angels appear to terrified shepherds in the fields outside Bethlehem, announcing the birth of Christ, shouldn’t we hear the words?

The answer lies in what Bach understood about encounters with the divine: sometimes the most profound truths can only be expressed through the language that exists beyond language itself.

Two Voices, Two Worlds

Listen carefully to the opening measures, and you’ll hear something remarkable. The music splits into two distinct characters, as clearly defined as protagonists in a play:

The strings and flutes: elegant, refined, moving in graceful arcs that seem to float rather than walk. This is the voice of heaven—seraphic, ethereal, speaking in the sophisticated language of what 18th-century theorist Albert Schweitzer called “angelic serenade.” The rhythm is a pastoral siciliano, that gently rocking 12/8 meter that evokes shepherds’ fields but in idealized, perfected form.

The oboes: earthier, simpler, more direct. These are the shepherds’ instruments, speaking in rustic tones that smell of wool and woodsmoke. When they enter, they don’t adopt the strings’ refinement. They speak in their own vernacular, their own simple phrases.

And here’s where Bach’s genius becomes almost unbearably beautiful: he makes them talk to each other.

The Architecture of Understanding

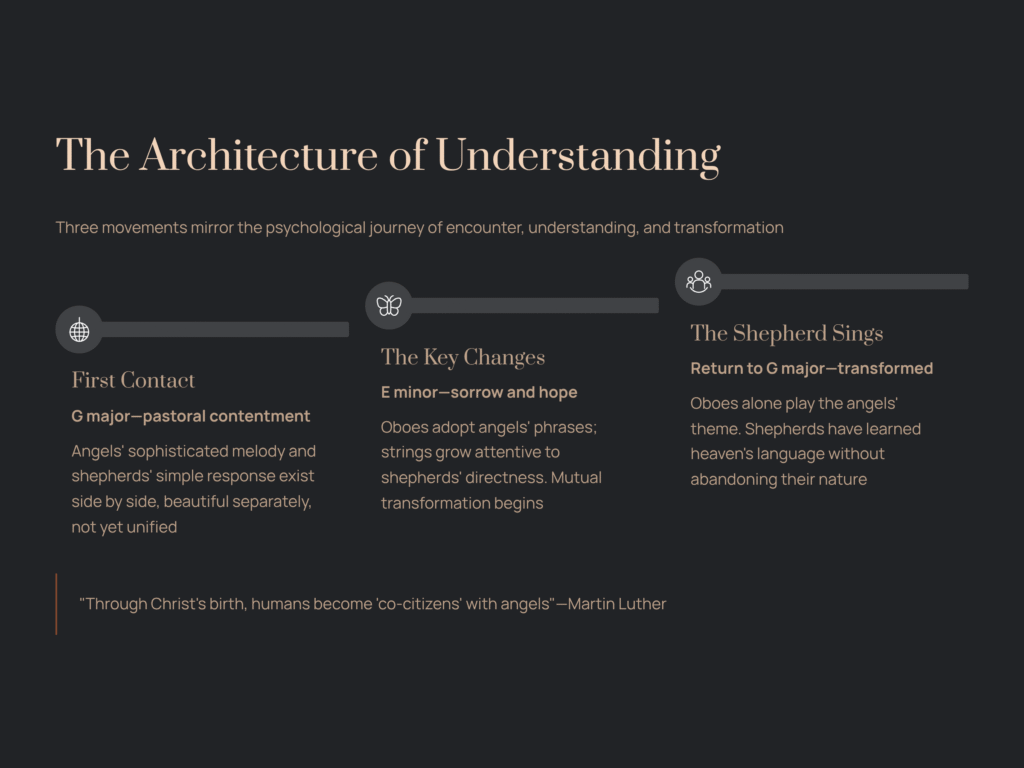

The Sinfonia unfolds in three movements—not marked in the score, but unmistakable in the listening. It’s a structure that mirrors the psychological journey of encounter, understanding, and transformation.

First Movement: The Distance Between Worlds

We begin in G major, the key of pastoral contentment. The strings present their theme first—think of it as an angelic voice reaching down from above. It’s lovely, complete, self-contained. Then the oboes respond, but not with the same melody. They offer their own theme, their own way of being in the world.

This is the moment of first contact, and Bach captures something essential about it: when two fundamentally different beings meet, they don’t immediately understand each other. The angel’s sophisticated melody and the shepherd’s simple response exist side by side, beautiful separately, but not yet unified.

Second Movement: The Key That Changes Everything

Then something shifts. We modulate to E minor—a key that in Baroque musical rhetoric signifies both sorrow and the hope of consolation. The harmonic ground beneath our feet changes, and with it, the relationship between our two musical characters.

Watch what happens now: the oboes begin to adopt elements of the strings’ melodic ideas. Not completely, not all at once, but gradually. Like someone learning a new language, they start incorporating the angels’ phrases into their own speech. Meanwhile, the strings seem to grow more attentive to the oboes’ simpler directness.

This is the music of mutual transformation. The divine descends; the human ascends. Neither loses their essential character, but both are changed by the encounter. It’s what Martin Luther meant when he wrote that through Christ’s birth, humans become “co-citizens” with angels—not that we become angels, but that the distance between heaven and earth becomes traversable.

Third Movement: When the Shepherd Sings the Angel’s Song

The return to G major should feel like coming home, except everything has changed. In the final minutes of the Sinfonia, Bach does something almost miraculous: the strings gradually withdraw, and we’re left with the oboes alone, playing the theme that originally belonged to the angels.

Think about what this means. The shepherds—represented by those earthbound oboes—have learned to speak the language of heaven. Not by abandoning their own nature (they still sound like oboes, rustic and direct), but by incorporating the divine voice into their own expression.

This is Bach’s theological vision made audible: the incarnation doesn’t just bring God down to us; it lifts us up to participate in the divine conversation.

The Sound of Sacred Space

I need to tell you something about how this music actually sounds when you hear it live, because recordings, as beautiful as they are, can’t quite capture it.

Imagine sitting in the cold stone interior of the Thomaskirche in Leipzig on December 26, 1734. The church is packed for the second day of Christmas celebrations. Candles flicker. Your breath makes small clouds in the frigid air. Then this music begins—not from the front of the church only, but surrounding you, because Bach placed the orchestra strategically throughout the space.

The strings create this shimmering halo of sound from one direction. The oboes, more localized, more particular, answer from another. You’re not just hearing a conversation; you’re standing inside it. You become the space where heaven and earth meet.

That’s what Bach understood about this story. The shepherds in the field weren’t just hearing about something; they were inside the event itself. The Sinfonia recreates that sense of being enveloped by the encounter.

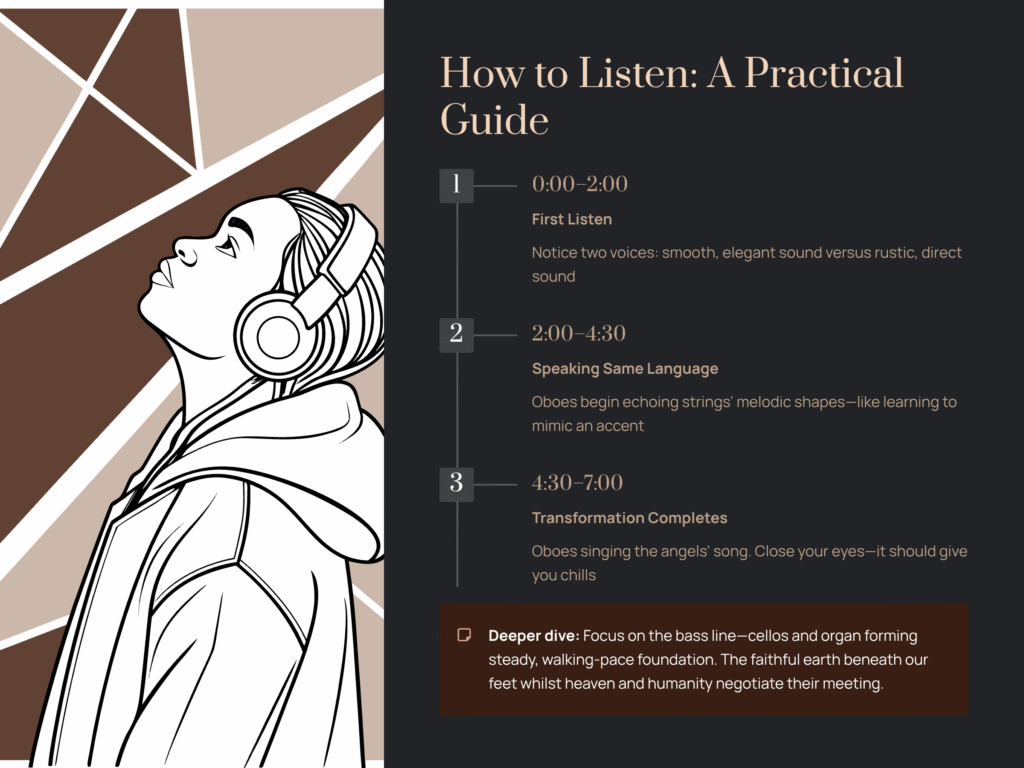

How to Listen: A Practical Guide

Let me give you a roadmap, because this seven-minute journey deserves your full attention:

0:00-2:00 – First listen for the two voices: Don’t worry about analysis yet. Just notice: there’s one kind of sound (smooth, elegant) and another kind (more rustic, direct). That’s enough for the first pass.

2:00-4:30 – Watch them start to speak the same language: Around the middle section, pay attention to how the oboes begin to echo the strings’ melodic shapes. It’s subtle, like watching someone slowly learning to mimic an accent.

4:30-7:00 – The transformation completes: In the final minutes, close your eyes and listen for the moment when you realize the oboes are singing the angels’ song. It should give you chills.

For the deeper dive: On your second or third listening, focus entirely on the bass line—the cellos and organ that form the foundation. Notice how steady and walking-pace it remains throughout all these transformations above it. That’s the continuo, the “continuous bass” that was the heartbeat of all Baroque music. It’s like the faithful earth beneath our feet while heaven and humanity negotiate their meeting.

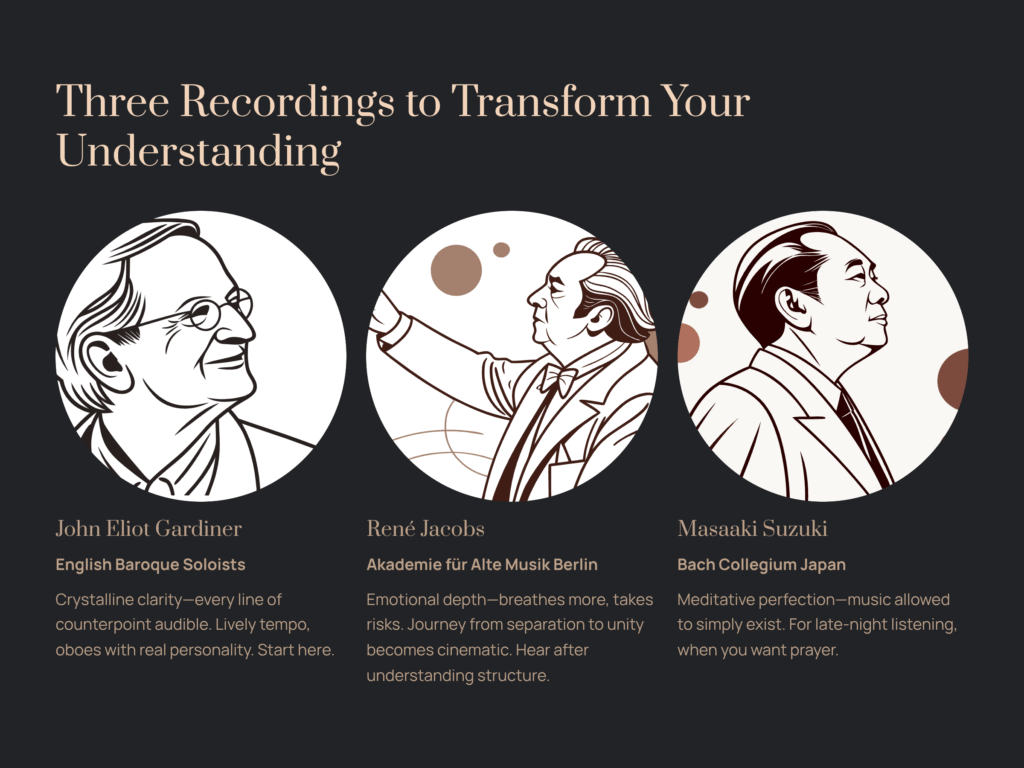

Three Recordings to Transform Your Understanding

If you’re ready to dive into actual recordings, these three interpretations will show you completely different facets of this work:

John Eliot Gardiner with the English Baroque Soloists: This is where I’d start. Gardiner’s interpretation is crystalline—you can hear every line of counterpoint, every instrumental conversation. The oboes have real personality; they don’t just blend into the texture. His tempo is lively without being rushed, giving you time to hear the structure reveal itself.

René Jacobs with Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin: If Gardiner gives you clarity, Jacobs gives you feeling. This recording breathes more, takes more risks with rubato and dynamic shading. The emotional arc of the piece—that journey from separation to unity—becomes almost cinematic. This is the interpretation to hear after you’ve understood the structure.

Masaaki Suzuki with Bach Collegium Japan: Suzuki’s approach is the most meditative. Everything is perfectly in place, perfectly balanced, and yet there’s this sense of inevitability to it, as if the music isn’t being performed but simply allowed to exist. For late-night listening, when you want to hear the Sinfonia as a kind of prayer, this is the one.

The Part That Comes After

I should tell you that this Sinfonia is just the beginning—the overture to Part II of the Christmas Oratorio. What follows is extraordinary: recitatives telling the shepherd story, chorales that let the congregation join the angels’ song, and one of Bach’s most beloved arias, “Schlafe, mein Liebster” (“Sleep, my beloved”), a lullaby for the infant Christ that uses the same oboe voices we’ve come to know as the shepherds.

But here’s what makes the Sinfonia so crucial: the musical themes and the instrumental characters we meet in these opening seven minutes return throughout Part II. Every time you hear those oboes later in the work, you’ll remember: these are the shepherds who learned to speak like angels. This musical past enriches everything that follows.

What This Music Teaches Us About Listening

I’ve spent years thinking about why this particular piece of music moves me so deeply, and I think I’ve finally figured it out. It’s not just about the beauty of the melodies or the cleverness of the counterpoint, though both are there in abundance.

It’s about Bach’s fundamental optimism about communication itself.

In a world where we’re constantly told that some gaps can’t be bridged—between cultures, between classes, between the sacred and the secular—here’s Bach saying: listen, even the distance between heaven and earth can be crossed through patient, mutual attention. The angels learn to value the shepherds’ simplicity; the shepherds learn to speak with the angels’ grace. Neither abandons who they are, but both are transformed by the encounter.

That’s not just theology. That’s a model for every difficult conversation, every moment when we face someone who seems to speak a completely different language than we do.

Maybe that’s why Bach chose to tell this story without words. Words can divide us, can define us into opposing camps. But listen—really listen—to how these instruments converse, and you’ll hear something more fundamental than language: the possibility of understanding itself.

A Final Thought While the Music Still Echoes

The next time you hear this Sinfonia—whether it’s during the Christmas season when it’s traditionally performed, or in the middle of summer when you need its particular kind of hope—I want you to think about a question:

What would it sound like if you learned to speak someone else’s musical language while they learned to speak yours? Not giving up your voice, but adding another dimension to it? Not winning an argument, but creating a new kind of conversation?

That’s what Bach is offering us in these seven minutes. Not just a beautiful piece of music, but a model for how we might inhabit the world together—angels and shepherds, heaven and earth, you and whoever you find most difficult to understand.

The Sinfonia ends, but the conversation it begins never really stops. It echoes through the rest of the Christmas Oratorio, through the rest of Bach’s sacred music, through the centuries into our own time.

All we have to do is listen. And maybe, if we’re brave enough, learn to sing each other’s songs.

For Further Exploration:

– The complete Part II of the Christmas Oratorio runs about 35 minutes and includes 10 additional movements after this Sinfonia

– Bach’s original performances took place over six days of Christmas celebrations in Leipzig, 1734-1735

– The instrumental forces Bach used were modest by modern standards—probably only 2-3 players per string part

– This music was originally performed not in a concert hall but as part of actual church services, integrated into the liturgy