Table of Contents

Debussy’s “The Snow is Dancing” from Children’s Corner

Do you remember the first time you saw snow? Not as an adult rushing to scrape windshields or worrying about traffic, but as a child—when those white crystals falling from the sky seemed like pure magic, like the sky itself was coming undone in the most beautiful way possible.

Claude Debussy remembered. Or perhaps he watched his three-year-old daughter, Claude-Emma (nicknamed “Chou-Chou”), press her nose against a window one winter afternoon in Paris, and he understood: this is what wonder looks like before we learn to call it “precipitation.”

“The Snow is Dancing” is the fourth piece in Debussy’s Children’s Corner suite, composed between 1906 and 1908. But it’s not really about snow at all. It’s about seeing snow—about that suspended moment when the familiar world transforms into something strange and hypnotic, when gravity itself seems negotiable, when each flake traces its own unpredictable path through air that suddenly feels alive with possibility.

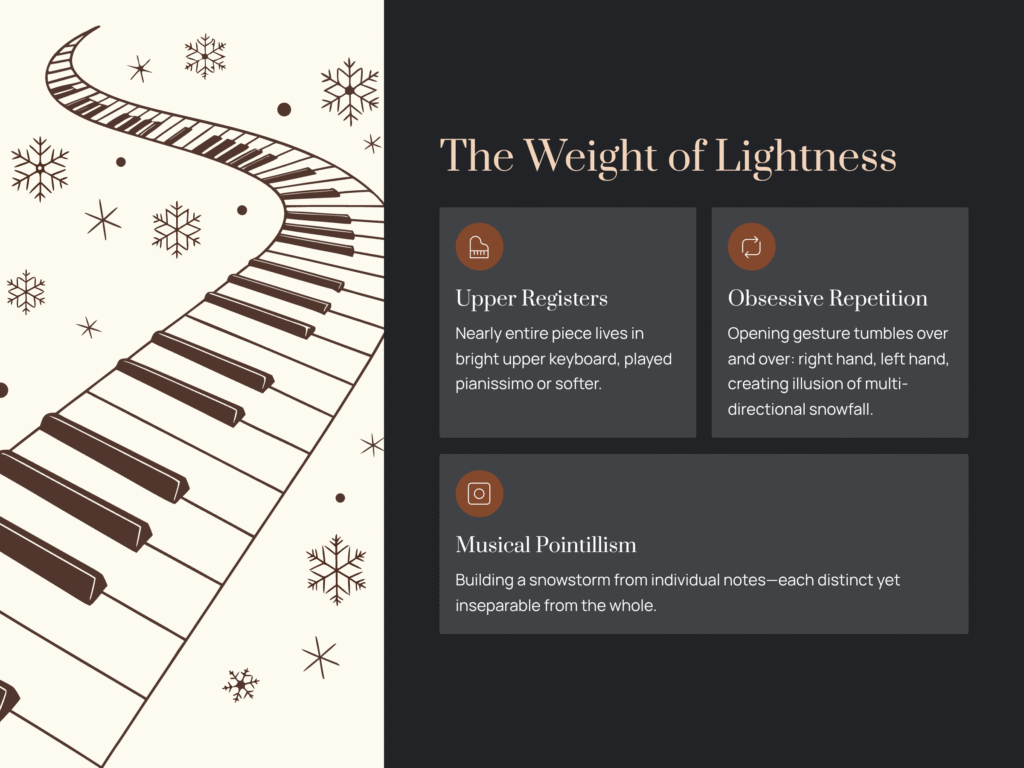

The Weight of Lightness

Here’s what fascinates me about this music: Debussy found a way to make the piano—an instrument of hammers striking strings—sound weightless. Nearly the entire piece lives in the bright upper registers of the keyboard, played pianissimo or softer. It’s as if he’s asking the instrument to forget its own nature, to become something closer to wind chimes or scattered light.

The opening gesture repeats obsessively, a small musical cell that tumbles over and over: right hand, left hand, right hand, left hand. This alternating pattern creates the illusion that snow is falling from multiple directions at once, that the air itself is filled with these tiny, dancing presences. It’s the musical equivalent of pointillism—those French painters who built entire landscapes from individual dots of color. Debussy builds a snowstorm from individual notes, each one distinct yet inseparable from the whole.

What the Hands Know

Watch a pianist’s hands during this piece, if you can. They tell their own story. The roles keep shifting: sometimes the right hand carries the main repeating figure while the left hand sketches harmonic shadows beneath; sometimes they trade places; sometimes both hands blur together in the middle registers like snowflakes colliding mid-air.

This isn’t just a compositional technique—it’s a philosophical statement. In nature, snow doesn’t fall in neat patterns or follow predictable paths. Each flake responds to invisible currents of air, to temperature gradients, to the chaos of weather itself. Debussy’s constantly shifting textures mirror this beautiful unpredictability. The music refuses to settle into comfortable patterns because snow itself never settles—it dances, it swirls, it disappears.

The Impressionist’s Secret

Debussy is often called an impressionist composer, and this piece shows you exactly why. But impressionism in music isn’t just about creating hazy, dream-like atmospheres. It’s about capturing the way perception actually works—the way our senses build reality from fragments and suggestions rather than solid facts.

Listen to the harmonies: they’re based in D minor, but the piece opens on an E, deliberately avoiding the “home” note. It’s as if the music begins mid-fall, already in motion. The modal harmonies—scales that don’t quite fit into our usual major or minor categories—create that floating, suspended quality, like snow that hasn’t yet decided whether to melt or accumulate.

There’s a technique here called a pedal point: a repeating ostinato pattern that anchors the entire piece while other melodies and harmonies drift above it. Think of it as the constant presence of winter itself—the season that continues regardless of our attention, the cold that persists whether we watch the snow or turn away.

What Happens When You Listen

About two and a half minutes. That’s all the time Debussy needs to conjure an entire winter afternoon. Here’s what to listen for:

In the first thirty seconds: Notice how soft everything is. This is music played at the very edge of audibility, as if Debussy is afraid of disturbing the snow. Let your ears adjust to this quiet world. Don’t turn up the volume—let the silence become part of the music.

Around the one-minute mark: The texture thickens slightly. More notes cluster together. This is when the snowfall intensifies, when individual flakes blur into a denser curtain of white. But notice: it’s still quiet. Even at its most “dramatic,” this piece never raises its voice.

In the middle section: The music shifts emotionally. There’s a moment of almost-anxiety here, as if the child watching has moved from wonder to a slight unease. Is the snow friendly or frightening? Beautiful or overwhelming? Debussy doesn’t answer—he lets both feelings coexist, because that’s how children experience the world: everything is simultaneously magical and slightly terrifying.

The ending: And then, without warning, it stops. No slowing down, no gentle fade, no comforting resolution. The music just ends, mid-gesture, as if the snow is still falling but we’ve simply looked away. This abrupt conclusion is deliberate—it captures something profound about winter, about nature’s indifference to our need for closure. The snow was dancing before we noticed, and it will continue dancing after we stop listening.

For the Hands That Play

If you’re a pianist, you know this piece is deceptively difficult. Not technically, in the way a Rachmaninoff prelude is difficult, but interpretively. The challenge isn’t hitting the right notes—it’s making those notes disappear into atmosphere, into suggestion.

Professional pianists use what’s called a “shallow pedal” here: just barely depressing the sustain pedal, enough to connect the tones without blurring them. It’s a razor’s edge between too dry and too muddy, and finding that balance requires the kind of control that only comes from years of practice. But you don’t need to play it to understand what it’s teaching: that restraint can be more powerful than force, that suggestion can be more evocative than statement.

Why This Matters

Debussy composed this music more than a century ago, but its emotional truth hasn’t aged. We still need reminders to see the world as children see it—not as a collection of problems to solve or conditions to endure, but as an endless source of wonder.

The snow is always dancing. The question is whether we’re watching.

I think of this piece often in December, when the year is winding down and everything feels weighted with expectation—holidays to plan, resolutions to make, a new year approaching with its demands and possibilities. “The Snow is Dancing” offers a different kind of wisdom: the wisdom of simply observing, of letting things be beautiful without needing to capture or explain them, of finding magic in repetition and pattern.

Debussy dedicated Children’s Corner to his daughter when she was three years old. She died tragically at fourteen, outliving her father by only a year. I think about that sometimes when I listen to this music—how Debussy caught something precious and fleeting, how these notes preserve a moment of childhood wonder that would otherwise have vanished completely.

The snow keeps dancing. The music keeps playing. And somewhere in that intersection of sound and silence, movement and stillness, we find something worth preserving: the memory of when the world was still new, when snow was not just frozen water but proof that the universe could be both beautiful and strange.

Press play. Close your eyes. Let the notes fall like snowflakes. And remember what it felt like to see winter for the very first time.

Listening Recommendations:

- Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (1962) — Crystalline precision meets poetic sensitivity

- Víkingur Ólafsson — A contemporary reading with remarkable clarity

- Paul Barton — Accessible interpretation perfect for first-time listeners

For Deeper Exploration:

Listen to the complete Children’s Corner suite to hear how this piece fits into Debussy’s portrait of childhood—from the playful “Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum” to the jazzy “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk.” Each piece captures a different facet of his daughter’s world, but “The Snow is Dancing” remains the most purely atmospheric, the most willing to surrender narrative for pure sensation.