Table of Contents

Why does music that seems to repeat itself never bore us? How can ten minutes feel like both an instant and eternity?

There’s a secret hidden in the score of Arvo Pärt’s Fratres—a mathematical formula that transforms into prayer, a structural puzzle that becomes meditation. This isn’t the kind of classical music that tells you a story with heroes and battles. Instead, it opens a door to a space where time bends, where three voices become one, where “brothers” are not just people but sounds holding hands in the dark.

If you’ve ever wanted to understand what happens when a composer strips away everything unnecessary and leaves only the essential, Fratres is where your journey begins.

The Mystery of Three Voices Becoming One

Imagine you’re standing in a medieval cathedral. A single bell rings—not once, but continuously, creating a foundation of sound that seems to hold up the entire building. Now imagine two more voices joining: one singing a slow, descending melody, another following like a shadow, exactly three notes higher. They move together, yet independently. They are separate, yet inseparable.

This is tintinnabuli, the technique Pärt invented after eight years of compositional silence. The word comes from Latin tintinnabulum, meaning “little bell.” But it’s more than a technique—it’s a philosophy captured in a simple equation:

1 + 1 = 1

The first “1” is the melody voice, wandering through a specific scale with its own subjective journey. The “+1” is the tintinnabuli voice, always ringing with just three notes—A, C, and E—like a bell that never stops resonating. And the “=1”? That’s the miracle: these two voices, though mathematically separate, merge into a single unified sound in our ears.

In Fratres, Pärt doesn’t just use this technique—he builds an entire architecture with it. The score restricts itself with almost monastic discipline: the lower voice can only use notes from the D harmonic minor scale (D, E, F, G, A, Bb, C#), while the middle voice is limited to just three notes of the A minor triad (A, C, E). Beneath everything, two notes—A and E—drone continuously, creating a perfect fifth that anchors the entire piece to the earth while allowing the upper voices to float like incense smoke.

This mathematical restriction isn’t a cage. It’s liberation. Like a haiku poet who chooses only seventeen syllables, Pärt finds infinity within limits.

Nine Variations, One Truth

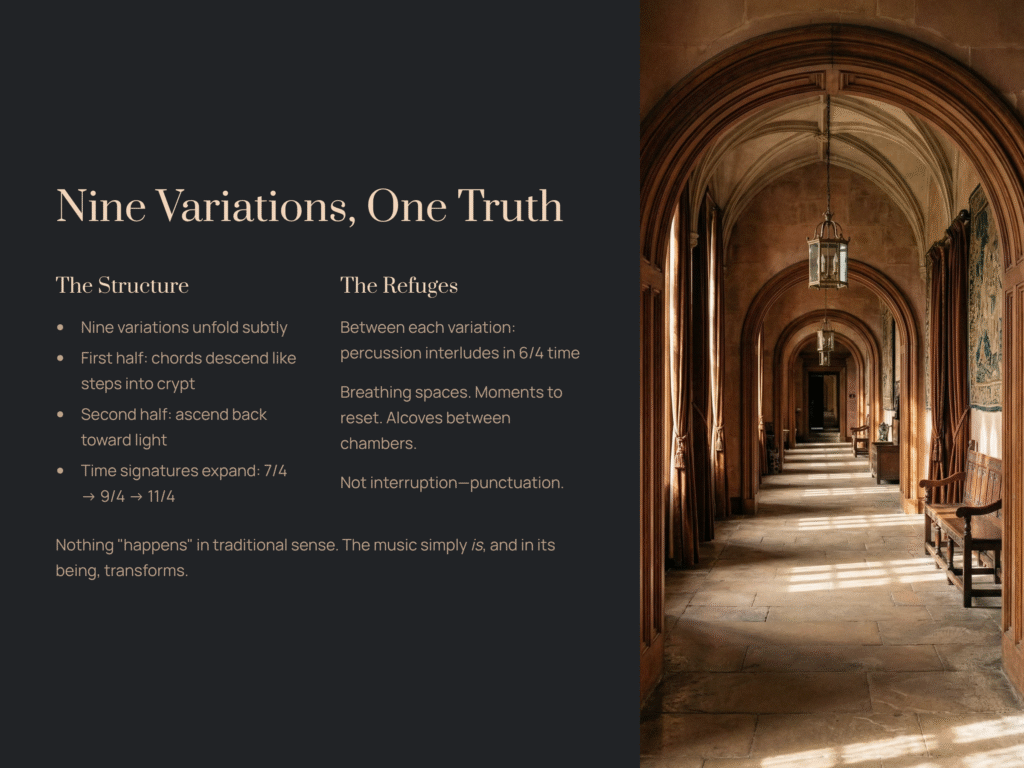

Here’s what makes Fratres structurally fascinating: it’s built on nine variations, but you might not notice them on first listen. Why? Because Pärt isn’t interested in showing off his cleverness. He’s after something deeper.

Each variation presents a chord sequence—some falling, some rising. In the first half, the chords descend like steps into a crypt. In the second half, they ascend back toward light. But between each variation stands something remarkable: a percussion “refuge.”

Picture this: you’re walking through a series of chambers, each one revealing a slightly different aspect of the same sacred object. Between each chamber, you step into a small alcove—a breathing space. That’s what the percussion interludes do. Scored in 6/4 time, lasting just two measures, these “refuges” give us a moment to reset, to breathe, to prepare for the next revelation. Some listeners compare this pattern to Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man,” but where Copland’s percussion announces triumph, Pärt’s announces contemplation.

The time signatures shift as the piece unfolds—from 7/4 to 9/4 to 11/4—and you can feel the musical space gradually expanding, like a room filling with light. Yet paradoxically, nothing really “happens” in the traditional sense. There’s no dramatic climax, no emotional crisis. The music simply is, and in its being, it transforms.

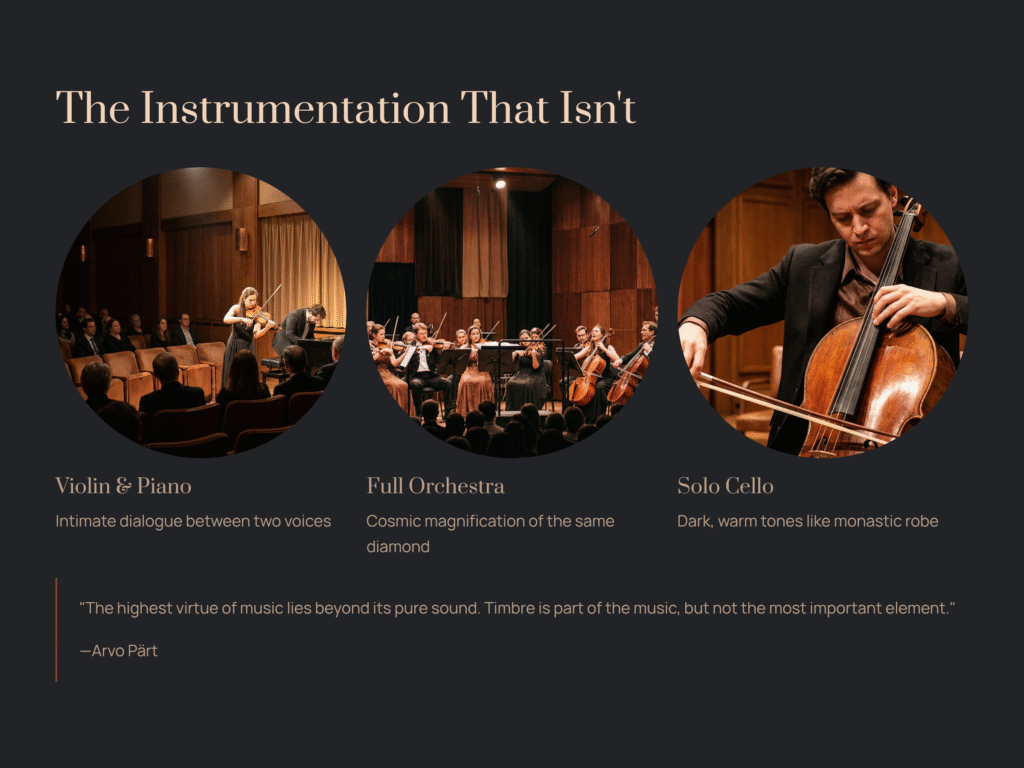

The Instrumentation That Isn’t

One of Fratres‘ most radical features is that it doesn’t insist on specific instruments. Pärt wrote it for “strings and percussion,” but he’s clear about his philosophy: “The highest virtue of music lies beyond its pure sound. The timbre of a particular instrument is part of the music, but it’s not the most important element.”

This isn’t laziness—it’s wisdom. Since 1977, Fratres has been performed by string quartets, multiple cellos, wind octets, violin and piano, even solo instruments. Each version reveals a different facet of the same diamond. The violin-and-piano version (first recorded by Gidon Kremer and Keith Jarrett) emphasizes the intimate dialogue between two instruments. The full string orchestra version magnifies the piece into something almost cosmic. The cello version wraps you in dark, warm tones like a monastic robe.

Which version is “right”? All of them. None of them. The music exists beyond its physical manifestation—a perfect demonstration of Pärt’s spiritual vision.

What You’ll Hear: A Listening Map

Let me walk you through what happens in those ten minutes, not chronologically, but experientially.

The Drone Foundation: From the first moment to the last, you’ll hear two notes—A and E—sustaining beneath everything else. This isn’t background music; it’s the ground of being. Like the hum of the universe itself, these notes create a sonic space where the other voices can exist. Don’t try to ignore them. Let them sink into your consciousness until you’re not sure if you’re hearing them or feeling them.

The Ghost Strings: Early in the piece, you’ll notice arpeggiated figures—broken chords—played on the open strings of the instruments. These sound almost spectral, like a choir heard through walls. They’re not trying to grab your attention; they’re establishing atmosphere, creating what one listener called “a gathering of ghosts in dim light.”

The Percussion Refuges: Every time you think you’ve settled into the music’s pattern, the percussion arrives. Pay attention to how this feels. It’s not interruption—it’s punctuation. A full stop that lets the previous phrase settle into your bones before the next one begins. Some listeners count these refuges; others just let them wash over like waves. Both approaches work.

The Subtle Variations: Here’s the challenge and the reward: each of the nine variations is different, but the differences are minute. The harmonic progression shifts. The register changes. The bowing techniques evolve. On first listen, you might think it’s all the same. On third listen, you’ll start hearing the variations. By the tenth listen, each one will feel completely distinct, like nine different prayers in the same language.

The Absence of Climax: Unlike most classical pieces that build to a dramatic peak, Fratres remains mysteriously level. There are moments of slight intensification, yes, but no catharsis in the traditional sense. This isn’t a bug—it’s a feature. Pärt wants you to experience time differently, to stop waiting for “what happens next” and start dwelling in “what is now.”

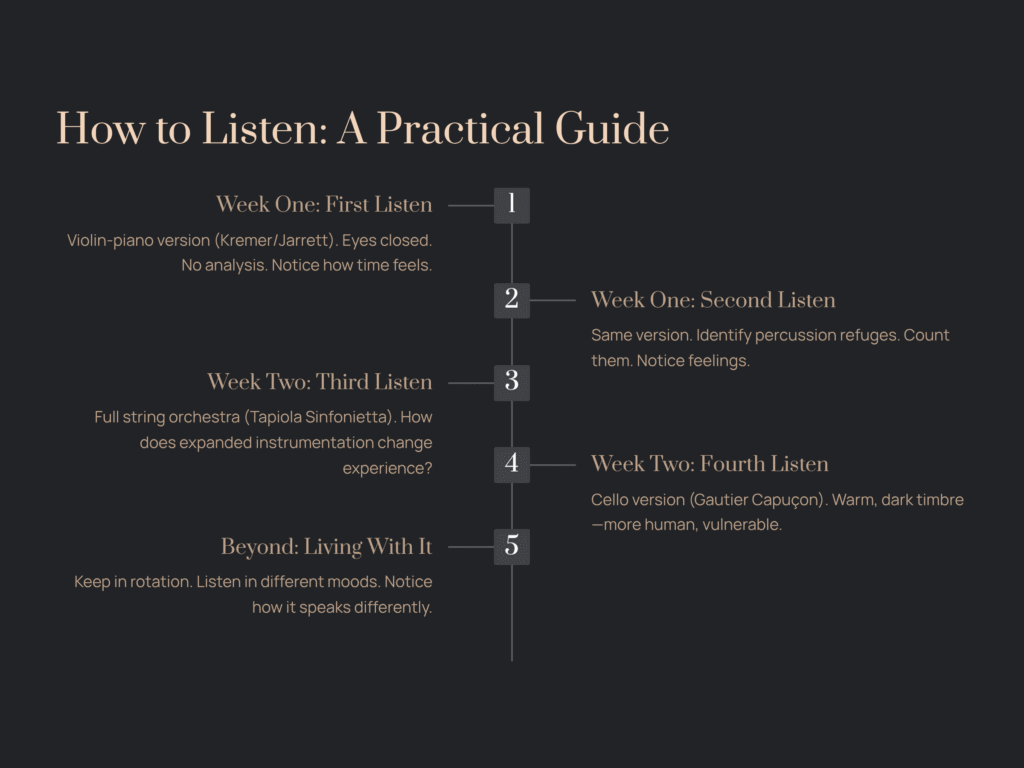

How to Listen: A Practical Guide

Fratres isn’t background music. It doesn’t want to accompany your dinner or your commute. It wants your full attention, at least for the first few listens. Here’s how to give it:

First Listening (Week One): Find twenty minutes when you won’t be interrupted. Not “almost won’t be interrupted”—actually won’t be. Sit or lie in a comfortable position. Close your eyes if that helps. Play the violin-and-piano version (Kremer/Jarrett on ECM’s “Tabula Rasa” album) all the way through. Don’t analyze. Don’t take notes. Just listen. Let the music be a sound-object in space. Notice how time feels.

When it’s over, don’t immediately jump up or switch to another piece. Sit with the silence for a minute. That silence is part of the piece.

Second Listening (Still Week One): Same version, but this time, try to identify the percussion refuges. Count them if you want. Notice how they make you feel. Do they comfort you? Frustrate you? Make you more alert?

Third Listening (Week Two): Switch to the full string orchestra version (try Tapiola Sinfonietta with Jean-Jacques Kantorow). Notice how the expanded instrumentation changes your experience. Is it more powerful? More distant? More intimate?

Fourth Listening (Week Two): Try the cello version (Gautier Capuçon with Orchestre de chambre de Paris). The warm, dark timbre of cellos gives Fratres a completely different character—more human, perhaps, more vulnerable.

Beyond Week Two: By now, you’ve heard Fratres at least four times. You’re starting to know it. Now comes the deep work: living with it. Keep it in your rotation. Listen when you’re stressed. Listen when you’re happy. Listen when you’re grieving. Notice how the same piece speaks differently depending on your inner state. This is what Pärt means by music existing “beyond its pure sound.”

The Philosophy Behind the Sound

Pärt converted to Orthodox Christianity during his eight years of silence, and his faith permeates Fratres without ever becoming preachy. He once said: “Time and timelessness are connected. This instant and eternity are struggling within us. And this is the cause of all our contradictions, our obstinacy, our narrow-mindedness, our faith and our grief.”

Fratres—Latin for “brothers”—embodies this struggle. The title doesn’t just mean human brothers. It means:

- Musical brothers: the three voices that harmonize while maintaining their independence

- Temporal brothers: repetition and variation, stability and movement, existing side by side

- Existential brothers: the individual soul and cosmic truth, dwelling together in sound

The piece never resolves this tension because life never resolves it. We live simultaneously in the moment and in eternity. We are individual and universal. We are changing and unchanging. Fratres holds all these contradictions without collapsing under their weight.

This is why the piece doesn’t have a traditional climax. Climax implies progress, development, movement toward a goal. But Pärt isn’t interested in going anywhere. He’s interested in being somewhere—specifically, in that paradoxical space where time touches eternity.

Questions You Might Be Asking

“Why so much repetition?”

Because repetition isn’t boredom—it’s meditation. Every spiritual tradition uses repetition: prayer beads, mantras, liturgical cycles. The mind needs repetition to settle, to stop its constant searching, to actually see what’s in front of it rather than looking for the next thing. After you’ve heard the same musical gesture five times, your analytical brain gives up trying to “figure it out,” and something deeper takes over. That’s when the real listening begins.

“Is this really music for beginners?”

Yes and no. Pärt’s tintinnabuli technique is actually easier to understand than, say, a Beethoven symphony with its complex development and multiple themes. There are no tricks here, no hidden references you need a music degree to catch. But Fratres demands something that might be harder than technical knowledge: patience and presence. If you can give it those, it will give you something profound in return.

“What if I still don’t like it?”

That’s completely valid. Not every piece speaks to every person. Some listeners need harmonic motion, melodic variety, rhythmic drive. Fratres offers very little of these things. It’s music for a particular mood, a particular need. Come back to it in six months or a year. Or don’t. There’s no shame in respectfully acknowledging that a highly regarded work isn’t for you.

“Can I understand this without religious belief?”

Absolutely. Pärt’s spirituality infuses the work, but the experience it creates—of stillness, of timelessness, of inner spaciousness—isn’t proprietary to any faith tradition. Atheists, agnostics, Buddhists, Muslims, and people of no particular belief have all found meaning in Fratres. The “eternal” it touches isn’t necessarily God. It might be the eternal that exists within every present moment, the depth available in any experience when we actually pay attention.

The Mathematical Miracle

Let me return to the structure one more time, because understanding it intellectually can deepen your emotional response.

Pärt uses strict mathematical rules to govern how the voices move. The middle voice—the tintinnabuli—always shadows the melody voice according to a formula. When the melody moves, the tintinnabuli adjusts to the nearest note in the A minor triad above or below it. This sounds mechanical, but the result is anything but cold. It’s like Bach’s counterpoint: the rules create freedom, not constraint.

The nine variations follow a symmetrical pattern. If you mapped them visually, you’d see an arch: rising, then falling, then rising again. But this architecture is so subtly constructed that you experience it as organic flow rather than imposed structure. It’s the difference between feeling the currents of a river and studying a hydrologist’s map.

The percussion refuges appear with perfect regularity—ten times throughout the piece—but they never feel mechanical because Pärt has carefully calibrated their duration and dynamics to feel like natural breathing. They’re metric, yes, but they’re also metered like breath, like heartbeat, like the rhythms of a body in meditation.

Living with Fratres

After you’ve spent time with Fratres, it might start appearing in unexpected moments. You’ll be washing dishes, and suddenly you’ll “hear” the percussion refuge in your mind. You’ll be walking at dusk, and the quality of light will remind you of how the second variation sounds. You’ll be waiting—in a line, for a bus, for news—and instead of impatience, you’ll feel something of the piece’s suspended timelessness.

This is Pärt’s gift: teaching us how to be present without striving, how to find depth in simplicity, how to hear the eternal ringing through the temporal like bells through fog.

Fratres isn’t programmatic. It doesn’t tell you what to think or feel. Instead, it creates a space—a sonic architecture—and invites you to dwell there for a while. What you discover in that space is up to you. Some people find peace. Others find grief. Some encounter mystery. Others encounter themselves.

The “brothers” of the title are ultimately you and the music, standing together in a darkened chamber, listening to something older than both of you, something that will outlast you, something that right now—in this moment of listening—belongs to you completely.