Table of Contents

When the Forest Speaks in Whispers

Have you ever walked alone through a forest in that hour when daylight begins to soften, when the world grows still enough that you can hear your own thoughts echoing back? That’s where this music lives.

Dvořák’s Silent Woods is not about technical brilliance or dramatic gestures. It’s about that moment when you’re walking through trees, and suddenly a memory surfaces—unbidden, achingly clear—and you have to stop and just breathe through it. The piece captures something we’ve all felt but rarely name: the way solitude can be both gentle and overwhelming, the way silence can hold entire conversations with ourselves.

If I were to describe this music in a single image, it would be this: a person walking slowly through a forest at dusk, footsteps soft on fallen leaves, stopping occasionally when the heart grows too full, then continuing on until the path curves into shadow and the walker becomes part of the deepening quiet.

The Music Born from Bohemian Earth

Antonín Dvořák wrote Silent Woods as part of a larger collection called From the Bohemian Forest, originally for piano four-hands—two players at one keyboard, hands crossing and voices interweaving like branches overhead. But Dvořák must have heard something more in this particular movement, because he later arranged it for cello and orchestra, and eventually in the intimate version we know best today: cello and piano.

The cello became the voice of the solitary walker. The piano became the forest itself—the dappled light, the rustling air, the earth underfoot. This wasn’t just a transcription; it was a transformation. What began as a pleasant salon piece became something more private, more confessional. The cello’s warmth and the piano’s delicate atmosphere create a space that feels almost sacred, a musical chapel in the woods where you can be alone with whatever weighs on your heart.

There’s no dramatic backstory here, no heartbreak or triumph that “explains” the music. Dvořák was simply drawing from the landscape of his homeland—those Czech forests he knew from childhood, where beech and oak grow dense and the light filters green through summer leaves. But somehow, in capturing that landscape, he also captured something universal about human solitude and the consolation we find in nature’s quiet company.

Walking Through the Music

The piece unfolds like an actual walk through the forest, and I find it helps to think of it in terms of landscape rather than musical structure. There’s no need to count measures or identify themes by number. Just follow the emotional contour, the way you’d follow a forest path without a map.

Entering the Forest

The piano begins with soft, sustained chords—not quite a melody, just an atmosphere settling around you. It’s the moment you step from the bright clearing into the shade of the trees, and your eyes need a moment to adjust. Everything becomes muted, softer, more inward.

Then the cello enters, low and warm, singing a melody that doesn’t announce itself but simply begins, as if it had been singing all along and you’re only now close enough to hear it. This is the main theme—call it the walking theme, the solitude theme, the remembering theme. It moves in long, unhurried phrases, each note held just long enough to create a sense of suspended time. The cello doesn’t perform for you; it simply exists beside you, like a companion who understands that sometimes the best company is silence.

Listen to how the melody curves. It rises gently, reaches a point of quiet intensity, then descends again, completing a full breath. This rising and falling becomes the heartbeat of the entire piece—the rhythm of walking, of breathing, of memory surfacing and submerging again.

The Path Deepens

As you walk deeper into the music, the cello climbs higher in its register. The melody grows more insistent, not louder but more urgent, as if the emotions that were merely present before are now demanding attention. The piano’s accompaniment becomes more complex, its harmonies shifting beneath the melody like shadows moving across the forest floor.

This is where the piece becomes most personal. If the opening was observation—noticing the beauty of the forest—this middle section is reflection, the point where outer landscape triggers inner landscape. What are you remembering as you walk? Who are you thinking of? The music doesn’t specify, and that’s its gift to us. The cello sings with a yearning quality, reaching upward, asking questions without words.

I always imagine this moment as that instant when a particular slant of light or quality of air suddenly recalls a specific day, a specific person, so vividly that the years between collapse. The cello’s voice becomes almost vocal here, singing with the kind of directness that bypasses intellect and speaks straight to whatever place inside us holds our tenderest feelings.

When the Heart Overflows

Then comes the moment of crisis—though that word is too dramatic for what happens. It’s more like a wave that builds and swells but never quite breaks. The cello surges upward, the piano supports with richer, fuller harmonies, and for a few measures, the contained emotion of the piece threatens to overflow its banks.

But Dvořák doesn’t let it explode. This isn’t a piece about catharsis. It’s about carrying your feelings, living with them, letting them pass through you without being destroyed by them. The cello reaches its highest, most vulnerable notes, holds there trembling for just a moment, then begins to descend again, accepting the natural ebb that follows every emotional flow.

This restraint is what makes the piece so moving. Life isn’t always about resolution or release. Sometimes it’s about walking through the feeling and out the other side, still intact, still yourself, but somehow changed by having allowed yourself to feel fully.

Return and Release

After that peak, the opening melody returns, but listen closely: it’s not quite the same. It’s like retracing your steps on a forest path and noticing things you missed the first time, or seeing them differently with changed eyes. The cello sings the theme again, but with a quality of acceptance now, even tenderness. The urgency has passed. What remains is not resignation but a kind of peace—the peace that comes from having felt something deeply and lived through it.

The piano’s accompaniment grows simpler, more spacious. The forest opens up again. You can see sky through the branches now. And then, gradually, both cello and piano begin to fade, not stopping abruptly but dissolving into the air like mist. The final notes don’t close the piece so much as allow it to drift away, becoming part of the silence it emerged from.

This ending is crucial. Dvořák doesn’t tie up the emotional journey with a neat bow. The music simply recedes, the way a path curves out of sight, leaving you standing alone again but somehow less alone than before, having shared this walk with someone—yourself, the composer, the musicians, the music itself—who understood.

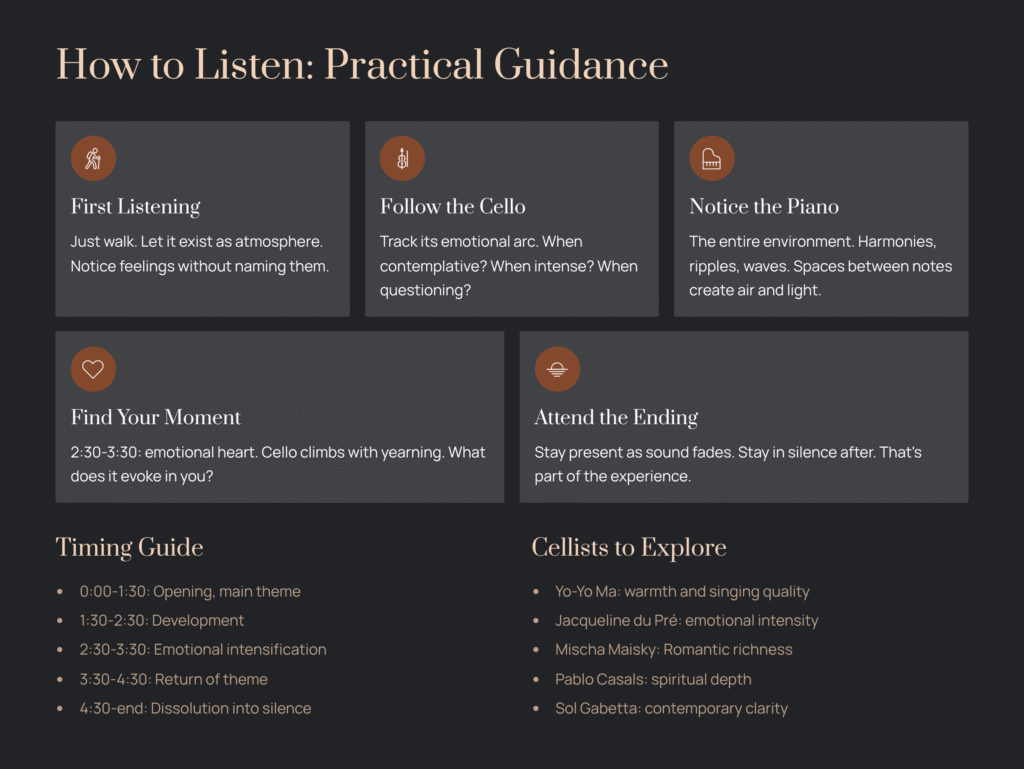

How to Listen: Practical Guidance

Let me offer you some specific ways to engage with this piece, because I’ve found that classical music reveals itself more fully when we give ourselves permission to listen actively, with intention.

First listening: Just walk. Put on the music and do something gentle—fold laundry, wash dishes, look out a window. Let it exist as background, as atmosphere. Don’t try to analyze. Just let your subconscious absorb the shape and mood of it. Notice what feelings arise without naming them.

Second listening: Follow the cello’s journey. This time, make the cello your focus. Imagine it as a voice telling you a story without words. When does it sound contemplative? When does it grow more intense? When does it seem to question, and when does it seem to answer? Track its emotional arc like you’d follow the plot of a novel.

Third listening: Notice the piano’s world. Now shift your attention to the accompaniment. The piano isn’t just background; it’s the entire environment. Listen to how its harmonies change, how sometimes it moves in gentle ripples and other times in stronger waves. Notice the spaces between its notes—the piano creates air and light as much as sound.

Fourth listening: Find your moment. In this listening, pay special attention to the middle section where the emotion intensifies. Around 2:30 to 3:30 in most recordings (timing varies by interpretation), you’ll hear the cello climb into its upper register with growing urgency. This is the emotional heart of the piece. Let yourself feel whatever comes up during those measures. What does that yearning quality evoke in you? What memory or feeling does it touch?

Fifth listening: Attend to the ending. Sometimes we rush through endings, ready to move on to the next thing. But this piece’s conclusion is essential. In the final minute, as both instruments grow quieter and finally fade away, try to stay completely present. Don’t let your mind jump ahead. Just stay with the diminishing sound until it’s gone, and then stay in the silence for a few moments after. That’s part of the experience too.

Listening with imagery: If you’re a visual person, try this: close your eyes and imagine walking through a specific forest you know, or create one in your imagination. Let the music score your walk. When the cello enters, you enter the forest. When it intensifies, you come to a place that holds significance. When it softens again, you’re walking toward home. The music and the mental landscape can enhance each other.

Listening with timing: If you want to track the piece’s architecture, here’s a rough guide (times vary by performance):

– 0:00-1:30: Opening, main theme introduced

– 1:30-2:30: Development, theme explored

– 2:30-3:30: Emotional intensification

– 3:30-4:30: Return of opening theme

– 4:30-end: Gradual dissolution into silence

Comparing performances: Once you know the piece well, listen to different cellists. Notice how each brings their own interpretation. Some linger on certain notes, creating more space and contemplation. Others move through the phrases with greater forward momentum. Some use more vibrato (that shimmering quality in the sound), others prefer a purer, more austere tone. There’s no “right” way—each performance reveals different facets of the music.

Try these cellists if you’re exploring:

– Yo-Yo Ma for warmth and singing quality

– Jacqueline du Pré for emotional intensity

– Mischa Maisky for Romantic richness

– Pablo Casals for historical perspective and spiritual depth

– Sol Gabetta for contemporary clarity

What the Forest Teaches

Here’s what I’ve come to understand after living with this piece for years: Silent Woods is about the particular grace that exists in solitude. Not loneliness, but chosen aloneness—the times we step away from the noise and demands of daily life and allow ourselves to simply be.

In our hyperconnected age, true quiet has become rare and even unsettling. We fill every silence with podcasts, music, notifications, anything to avoid being alone with our thoughts. But Dvořák reminds us of what we lose in that constant distraction: the chance to process our experiences, to feel our feelings fully, to integrate our memories into the ongoing story we tell ourselves about our lives.

The forest in this music isn’t an escape from reality. It’s a place to encounter reality more honestly, stripped of social performance and external expectation. When you walk alone in the woods, you can’t pretend to be anyone but yourself. The trees don’t judge. The silence doesn’t demand anything. You’re free to feel what you actually feel, think what you actually think.

And yet—and this is the piece’s deeper gift—that solitude isn’t isolation. Dvořák’s music creates a kind of companionship, a sense that someone else has walked this path before and felt what you’re feeling. The cello’s voice becomes a friend who doesn’t need you to explain, who simply walks beside you in understanding silence. This is what great music does: it makes us feel less alone in our most solitary moments.

The piece also teaches us about emotional containment, about carrying our feelings with dignity. The middle section’s surge of intensity never becomes melodramatic or self-indulgent. Dvořák shows us that you can feel deeply—even painfully—without losing yourself in the feeling. The music holds the emotion without being consumed by it, and in doing so, it models a kind of emotional maturity we might aspire to in our own lives.

Finally, there’s that ending, that gentle dissolution into silence. It suggests that some things don’t need resolution. Some walks end not with arrival but simply with the walking itself. Some emotions don’t need to be solved or fixed, just felt and released. The music fades away, and we’re left with ourselves again—but perhaps with a greater acceptance of who we are in our solitude, a deeper appreciation for the quiet spaces in our lives.

A Final Invitation

I’d suggest this: Find a time when you have fifteen uninterrupted minutes. Not while you’re driving or working, but a time when you can simply sit with the music. Maybe it’s evening, when the day is winding down. Maybe it’s early morning, before the world makes its demands.

Put on Silent Woods. Close your eyes if that helps, or gaze softly at something neutral—a wall, a window, the floor. Let the music create its forest around you. Don’t worry about understanding it or analyzing it correctly. Just walk through it. Let it be the space where whatever you’ve been carrying can finally be set down, at least for these few minutes.

When it ends and the silence settles, sit in that silence for a moment before moving on to the next thing. That silence is part of the gift.

We all need places to walk alone with our thoughts, forests where we can let our hearts speak without words. Dvořák’s Silent Woods creates such a place, one we can visit whenever we need refuge from the noise, whenever we need to remember that solitude can be not just bearable but beautiful—a space where we meet ourselves with honesty and, perhaps, with grace.

The forest is always there, waiting. All you have to do is press play and step inside.