Table of Contents

The Secret of a Melody That Never Breaks

Have you ever wondered what happens when a melody refuses to stop? Not in the sense of perpetual motion, but in the way a single thread of sound keeps transforming, evolving, never quite repeating itself yet always feeling familiar—like watching the same river that’s never the same water twice?

This is the mystery at the heart of Mozart’s “Laudate Dominum,” the fifth and most radiant movement of his Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339. Written in 1780 for Salzburg Cathedral, this piece does something quietly revolutionary: it creates what musicians call a “through-melody”—a continuous melodic line that flows from beginning to end without traditional sectional breaks. It’s not a strophic song with verses. It’s not a da capo aria that circles back. It’s a single, unbroken arc of sound that carries us from “Praise the Lord” to “Amen” as if we’ve been breathing with one long, sustained breath.

But here’s what makes this even more fascinating: Mozart composed this under constraint. His employer, the conservative Archbishop Colloredo, demanded that each psalm in the Vesperae be written as a continuous movement—no operatic arias, no divisions into separate ensembles. What could have been a limitation became, in Mozart’s hands, an opportunity to explore something profound about the nature of melody itself.

The Architecture of Air: Understanding the Through-Melody Form

Let me walk you through what makes this structure so special. The piece is in F major, set in a gentle 6/8 time that creates a lilting, almost boat-like motion—imagine being rocked on quiet water. The soprano soloist enters alone, her voice rising softly up the F major scale and descending again, tracing the contours of prayer itself.

Now, in most pieces, you’d expect this opening theme to come back, to be repeated or developed in obvious ways. But Mozart does something subtler. The melody is constantly changing, constantly finding new ways to express the same spiritual impulse. Yet three times throughout the piece—at measures 22, 39, and 65—he brings back the same motivic gesture, like a touchstone, a moment of recognition. It’s as if, in the midst of this flowing prayer, we keep returning to the same word: Dominum, the Lord, the anchor point of devotion.

The genius lies in how he connects these moments. Between them, the melody transforms through what seems like an infinite series of variations. Mozart uses secondary dominant seventh chords—those rich, tension-filled harmonies that pull us forward—to create a sense of yearning, of reaching toward something beyond the notes themselves. There’s even an F-sharp minor ninth chord that appears like a shadow crossing the sun, adding depth and complexity to what might otherwise feel too simple, too sweet.

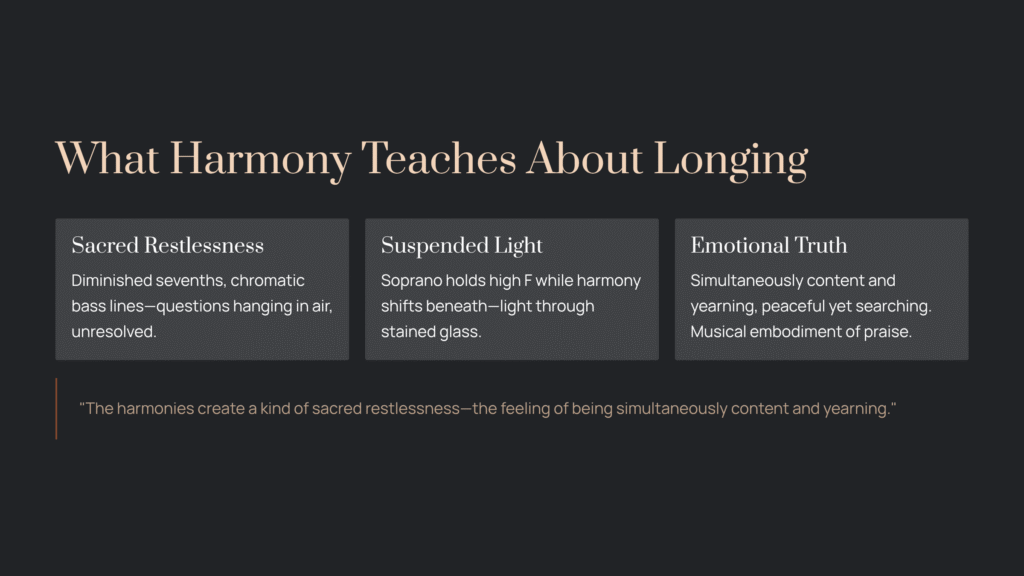

What the Harmony Teaches Us About Longing

I want you to focus on something specific in your next listening: the way Mozart uses harmonic tension to mirror spiritual longing. Throughout the piece, he employs diminished seventh chords and chromatic bass lines—these are the musical equivalent of questions that hang in the air, unresolved. When the soprano voice reaches its highest F and holds it, suspended above the orchestra, the harmony beneath her shifts and pulses like light through stained glass.

This isn’t just technical wizardry (though it is that—Mozart’s use of suspensions, trills, and decorative figures is exquisite). It’s emotional truth translated into sound. The harmonies create what I can only describe as a kind of sacred restlessness—the feeling of being simultaneously content and yearning, peaceful yet searching. It’s the musical embodiment of “Laudate Dominum omnes gentes”—”Praise the Lord, all nations”—a call that reaches outward and inward at the same time.

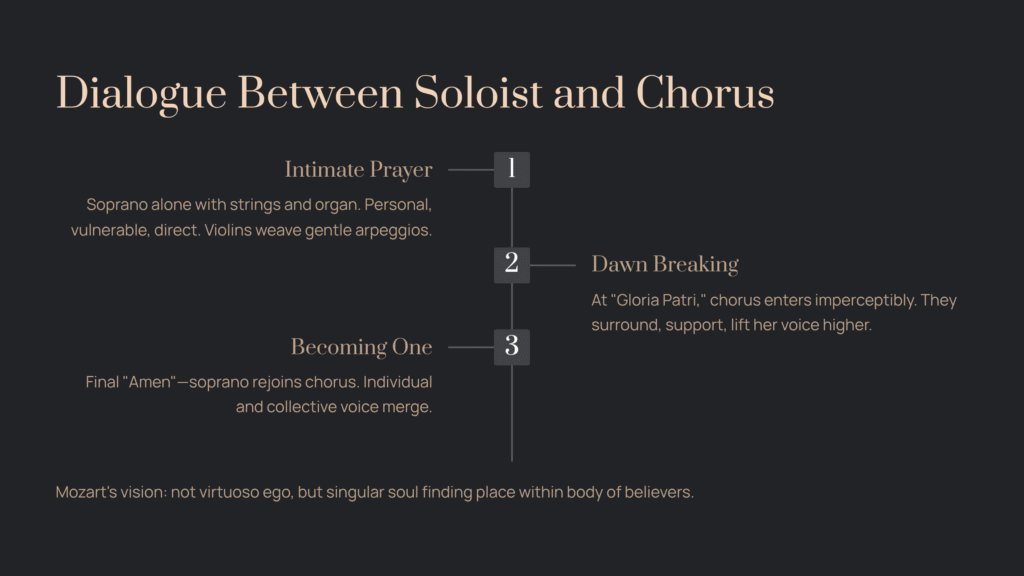

The Dialogue Between Soloist and Chorus: A Study in Humility

One of the most beautiful aspects of the original version is the relationship between the soprano soloist and the chorus. For most of the piece, the soprano sings alone, accompanied only by strings and organ. Her voice has the quality of intimate prayer—personal, vulnerable, direct. The violins weave around her in gentle arpeggios, a sixteenth-note filigree that feels like breath made visible.

Then, at the words “Gloria Patri”—”Glory to the Father”—the chorus enters, not dramatically but almost imperceptibly, like dawn breaking. They don’t overpower the soloist; instead, they surround her, support her, lift her voice higher. In the final “Amen,” the soprano rejoins them, and individual voice and collective voice become one.

This is Mozart’s vision of sacred music at its most profound: not the ego of the virtuoso performer, but the merging of singular and communal praise. The soprano’s continuous melody and the chorus’s supportive entrance create a theological statement—the individual soul finding its place within the body of believers.

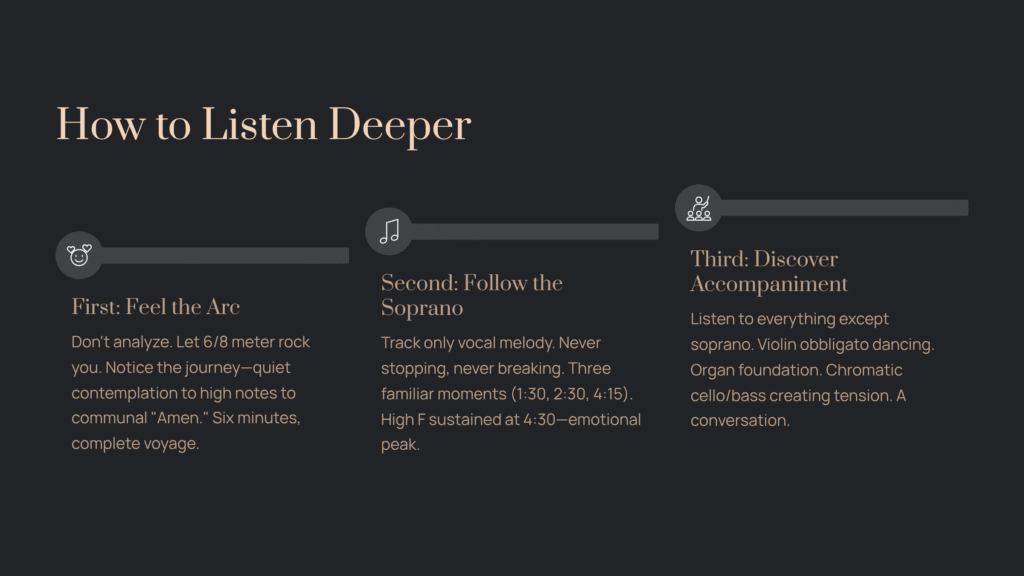

A Practical Guide: How to Listen Deeper

Let me offer you a three-stage approach to experiencing this piece more fully:

First listening: Feel the arc. Don’t analyze anything. Just let the 6/8 meter rock you. Notice how the piece makes you feel—the way it begins in quiet contemplation, gradually builds in intensity (especially when the soprano reaches those high notes), and then settles into the communal “Amen.” The piece is only about six minutes long, but it should feel like a complete journey.

Second listening: Follow the soprano’s line. This time, track only the vocal melody. Notice how it flows—never stopping, never breaking into obvious sections. Pay special attention to those three moments (around 1:30, 2:30, and 4:15 in most performances) where you hear that familiar motif return. It’s like meeting an old friend in a crowd. Also, listen for the moment—usually around 4:30—when the soprano sustains a high F while the harmony shifts beneath her. That’s the emotional peak of the entire piece.

Third listening: Discover the accompaniment. Now listen to everything except the soprano. Focus on the violin obbligato—that delicate countermelody that dances around the voice. Notice how the organ provides harmonic foundation. Listen for the cello and bass lines, which often move chromatically (in half-steps), creating subtle tension and release. The accompaniment isn’t just support; it’s a conversation partner.

Recommended Performances: Different Windows into the Same Light

If you’re new to this piece, I suggest starting with Katherine Jenkins’ version. Her clear, pure tone makes Mozart’s melodic line crystalline—you can hear every contour, every nuance. There’s something about her approach that embodies what Mozart himself said: “Melody is the essence of music.” She doesn’t over-interpret; she lets the line speak for itself.

For a different experience, seek out Aksel Rykkvin’s recording with treble (boy soprano) voice. There’s an otherworldly quality to the timbre—transparent, almost ethereal—that emphasizes the spiritual dimension of the text. The innocence of the voice adds a layer of meaning that’s harder to achieve with a mature soprano.

Historical Context: The Last of Salzburg

Understanding when this was written adds another dimension to our appreciation. “Laudate Dominum” was Mozart’s final liturgical work composed in Salzburg, before his move to Vienna and his encounter with the music of J.S. Bach and Handel. This matters because it shows us Mozart at a transitional moment—still rooted in the Salzburg church music tradition, yet already reaching toward something more personal, more emotionally direct.

Archbishop Colloredo wanted church music that was efficient, dignified, and traditional. What he got from Mozart was all of those things, but also something he probably didn’t expect: music that balanced stile antico (the old contrapuntal church style) with a modern, almost operatic beauty. The movement just before “Laudate Dominum”—”Laudate pueri”—is written in strict counterpoint, austere and formal. Then comes this piece, with its flowing, lyrical melody. The contrast is intentional, even radical. It’s Mozart saying: both approaches to the sacred are valid. Intellectual rigor and emotional immediacy can coexist.

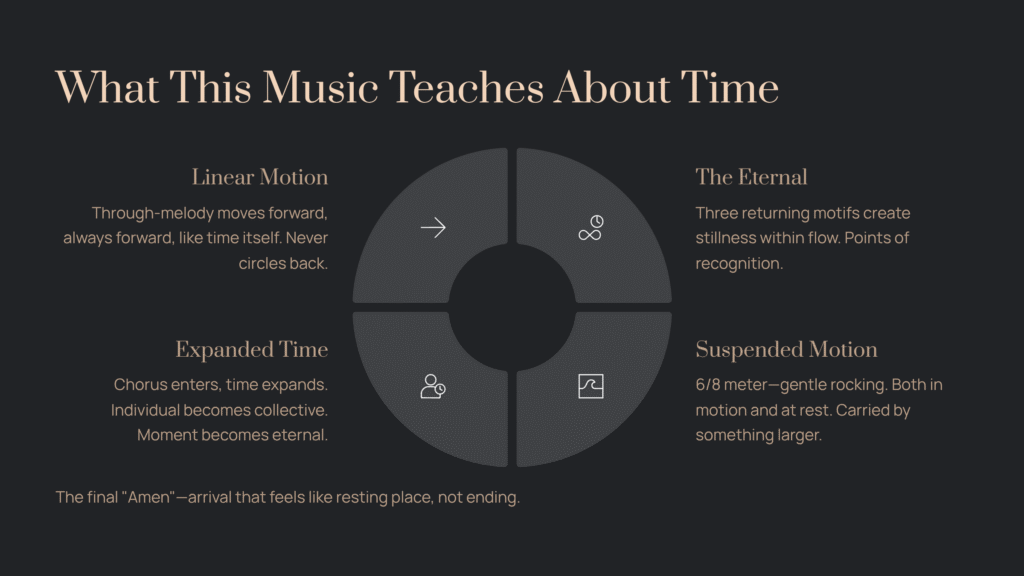

What This Music Teaches Us About Time

I’ve come to think of “Laudate Dominum” as a meditation on time itself. The through-melody form means that the piece doesn’t circle back on itself; it moves forward, always forward, like time. Yet within that forward motion, there’s a sense of the eternal—the way those three returning motifs create points of stillness within the flow.

This is what makes the piece feel both comforting and slightly disorienting. We’re moving through it, but we’re also held within it. It’s linear but also somehow suspended. The 6/8 meter contributes to this feeling—that gentle rocking motion creates a sense of being both in motion and at rest, like being carried by something larger than ourselves.

When the chorus enters near the end, time seems to expand. The individual prayer becomes collective worship. The moment becomes eternal. And in the final “Amen”—when soprano and chorus breathe together—there’s a sense of arrival that doesn’t feel like an ending so much as a resting place.

A Closing Thought: The Paradox of Sacred Beauty

What Mozart achieves in these six minutes is something I find both simple and inexplicable. He takes one of the shortest psalms in the Bible—just two verses—and creates a musical experience that feels vast, comprehensive, complete. He uses technical sophistication (those secondary dominants, those diminished sevenths, that chromatic bass) in service of something that sounds effortless, natural, inevitable.

The piece is sacred music, yes—written for a specific liturgical function in a specific cathedral. But it transcends its original purpose. You don’t need to be religious to be moved by it. You don’t need to understand Latin or know anything about church music traditions. What you need is the willingness to listen to a single voice tracing a single melodic arc, and to recognize in that arc something universal: the human impulse to praise, to reach beyond ourselves, to find meaning in sound.

The next time you hear “Laudate Dominum,” try this: close your eyes and imagine that soprano line as a single thread of light, continuous and unbroken from first note to last. Watch how it rises and falls, how it curves and straightens, how it transforms while remaining itself. That’s the mystery Mozart is showing us—how something can be constantly changing and eternally the same, how a melody can be both time-bound and timeless, how six minutes of music can feel like it holds eternity within it.

That’s the gift of the through-melody form. That’s the secret Mozart discovered under constraint. And that’s why, more than two hundred years later, we’re still listening, still discovering, still finding ourselves held within that continuous, transforming, never-quite-repeating arc of sound.