📑 Table of Contents

There is a particular quality to the stillness before dawn on Christmas morning. Not the jubilant chaos of unwrapping presents, not the cheerful noise of carols sung around a piano—but something quieter, almost sacred. A hush that settles over the world like fresh snowfall.

Camille Saint-Saëns captured this precise feeling in 1858, composing a Christmas Oratorio that refuses to celebrate with fanfare. Instead, the opening Prélude invites us into a different kind of Christmas experience: one of contemplation, of wondering at mysteries too profound for words.

The Story Behind the Music

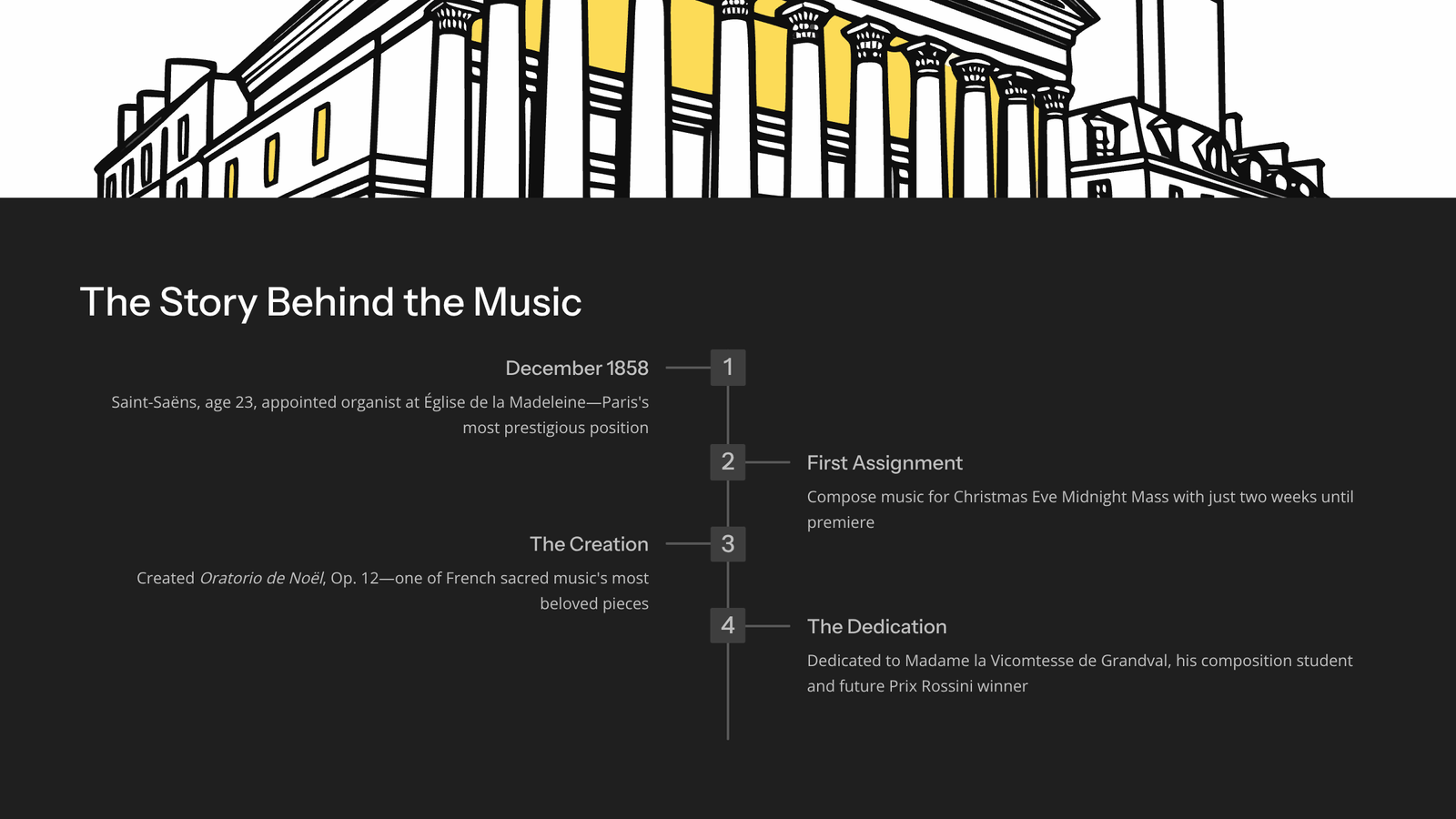

Picture Paris in December 1858. A young man of twenty-three has just received one of the most prestigious appointments in French music—organist at the Église de la Madeleine, the official church of the Second Empire. This was no ordinary position. The previous organist, Louis James Alfred Lefébure-Wély, had been the most celebrated keyboard player in all of Paris.

Camille Saint-Saëns now carried the weight of that legacy on his shoulders.

His first major assignment? Compose music for the Christmas Eve Midnight Mass, just days away. With barely two weeks until the premiere, Saint-Saëns created something that would become one of the most beloved pieces of French sacred music—his Oratorio de Noël, Op. 12.

The young composer dedicated this work to Madame la Vicomtesse de Grandval, born Clémence de Reiset—one of his composition students who would herself become a celebrated composer, eventually winning the prestigious Prix Rossini for her own oratorio. In an era when female composers faced countless obstacles, Saint-Saëns recognized and championed her talent.

What Makes This Prélude So Special

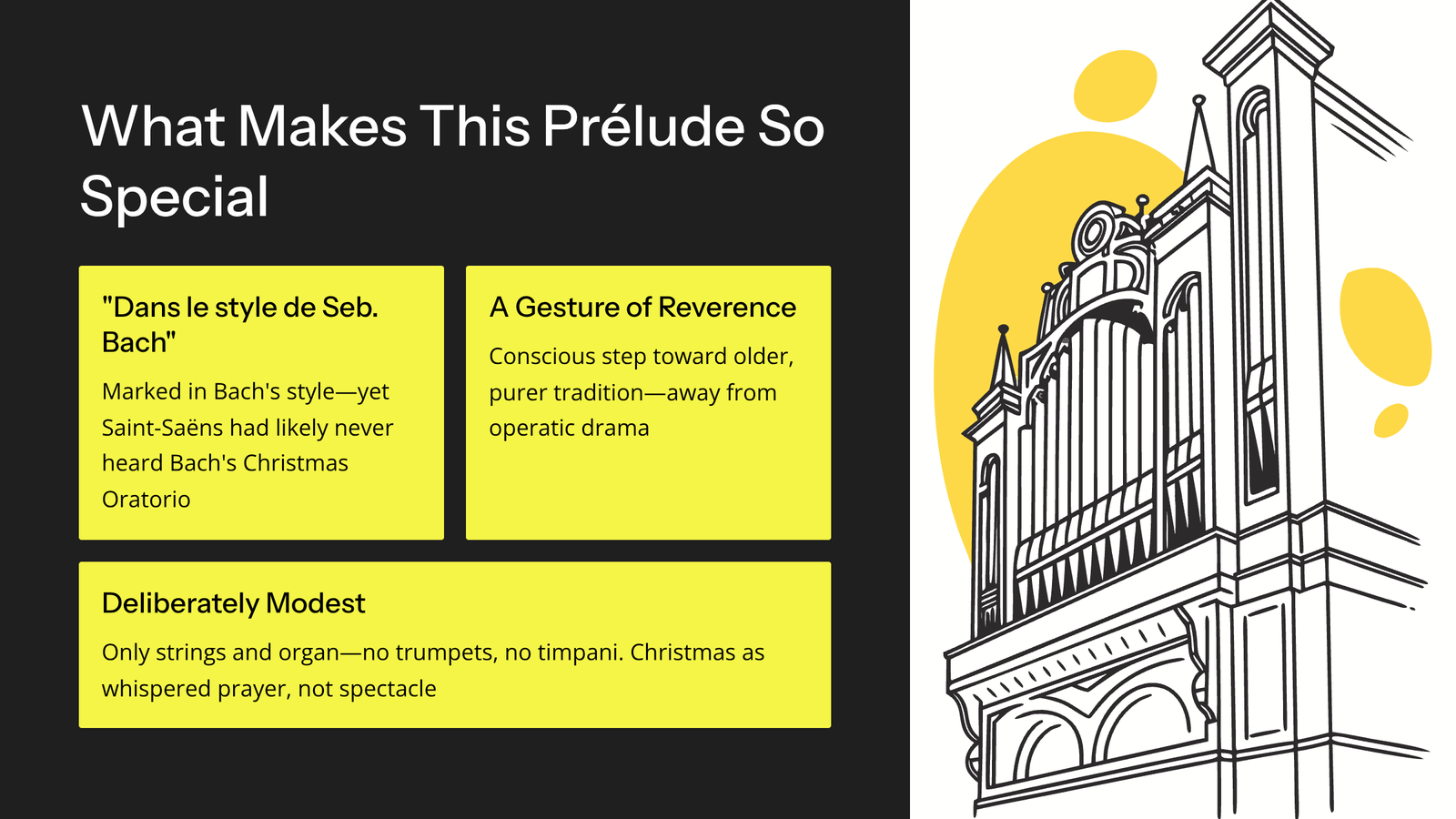

Saint-Saëns marked his Prélude “Dans le style de Seb. Bach”—in the style of Sebastian Bach. But here is a wonderful irony that scholars have uncovered: the young composer likely had never even heard Bach’s own Christmas Oratorio at this point in his life. In 1858 France, Bach remained a somewhat obscure figure, more legend than everyday listening.

So what does “Bach style” mean here? Think of it as a gesture of reverence toward an older, purer musical tradition—a conscious step away from the operatic drama that dominated French sacred music of the time. Saint-Saëns created something deliberately modest, intimate, and profoundly sincere.

The instrumentation tells this story clearly. There are no trumpets heralding the birth of a king, no timpani rolls announcing triumph. Instead, we hear only strings and organ—the bare essentials of church music, stripped of all theatrical excess. This is Christmas not as spectacle, but as whispered prayer.

A Guided Journey Through the Music

Opening Moments (0:00–0:30)

The organ breathes to life with sustained, gentle harmonies—like candlelight flickering in a stone chapel. Almost immediately, the first violins introduce the main theme: a pastoral melody so simple it could be a shepherd’s tune, played on a wooden flute under starlit skies.

Listen for the undulating arpeggios in the lower strings. They create a rocking motion, almost like a lullaby. Or perhaps like the quiet footsteps of travelers approaching a humble stable.

The Heart of the Prélude (0:30–2:00)

The pastoral theme repeats, but each time Saint-Saëns clothes it in slightly different textures. The violas join the conversation. The cellos add warmth to the foundation. The organ swells almost imperceptibly, then retreats.

What strikes you here is the absence of drama. There are no sudden outbursts, no virtuosic displays. The music seems to exist outside of time, suspended in that eternal moment before the shepherds arrive, before the angels sing—the last quiet breath of a world about to change forever.

A Gentle Deepening (2:00–2:50)

If there is a “development” section, it arrives here with remarkable subtlety. The harmonies become slightly richer. The organ takes on a fuller voice. But even at its most intense, the music never rises above a gentle mezzo-forte.

Imagine watching night slowly lighten toward dawn. Nothing sudden—just the gradual, inevitable unfolding of something beautiful.

Return and Resolution (2:50–3:10)

The pastoral theme returns one final time, simplified now, almost whispered. The organ holds its last chord as the strings fade into silence. There is no grand conclusion—only the sense of a door quietly opened, an invitation extended.

Recommended Recordings

For Your First Listen

The 1981 recording conducted by Anders Eby with the Royal Opera Theater Orchestra and Mikaeli Chamber Choir offers an ideal introduction. The interpretation emphasizes warmth and intimacy without excessive sentimentality. As a bonus, this recording features a young Anne Sofie von Otter—captured just before she became an international star.

For Audiophiles

Look for period-instrument performances that use gut strings and historic organ registrations. These bring out the French Romantic character that Saint-Saëns would have expected in 1858.

For Late-Night Listening

Any recording that maintains extreme dynamic restraint will serve you well. This is music for 2 AM on Christmas Eve, when the house has finally gone quiet and you find yourself staring at tree lights in the darkness.

Why This Music Matters Today

Some critics have called Saint-Saëns’ Christmas Oratorio “relentlessly contemplative”—and they don’t always mean it as a compliment. In an age of spectacular holiday productions, this music offers no pyrotechnics.

But perhaps that is precisely its gift.

We live surrounded by noise, especially during the holiday season. Advertisements shout. Parties roar. Even our supposedly peaceful moments come packaged with curated playlists designed to optimize our emotional responses.

The Prélude from Saint-Saëns’ Christmas Oratorio asks something different of us. It asks us to sit still. To stop expecting something to happen. To simply be present in a moment of musical stillness—the way the shepherds must have sat in stunned silence before the manger, all their words inadequate to the mystery before them.

This is not background music. It is foreground music—music that rewards your full attention with something increasingly rare in our distracted world: genuine peace.

Final Thoughts

When Saint-Saëns walked into the Église de la Madeleine on Christmas Eve 1858, he was a young man still proving himself to the musical world. The oratorio he performed that night would become a cornerstone of French sacred repertoire, but he could not have known that then.

What he did know—what comes through in every measure of this Prélude—is that some mysteries are best approached in silence. The birth at Bethlehem was not, in its first moments, a celebration. It was a bewilderment. A wonder. A hush that fell over a stable while stars wheeled overhead.

Saint-Saëns understood this. And in three quiet minutes of strings and organ, he invites us to understand it too.

Press play. Turn down the lights. And let the shepherds’ vigil begin.

![Read more about the article Air Cooled CPU vs. Water Cooled CPU: Choose the right cooling system for PCs out of 2 [Part.2]](https://rvmden.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Air-Cooled-CPU-vs-2-300x169.png)