📑 Table of Contents

- The Triple Blow That Changed Everything in Mahler’s Life

- Finding Ancient Chinese Wisdom in the Austrian Mountains

- Why Mahler Called This a Symphony (But Also Did Not)

- The Two Ancient Poets Speaking Across Time

- What You Actually Hear: A Guide to Mahler’s Der Abschied

- What Makes This Movement So Devastatingly Effective

- Recommended Recordings for First-Time Mahler Listeners

- Listening Tips for Der Abschied: Practical Suggestions

- What This Music Might Change in You

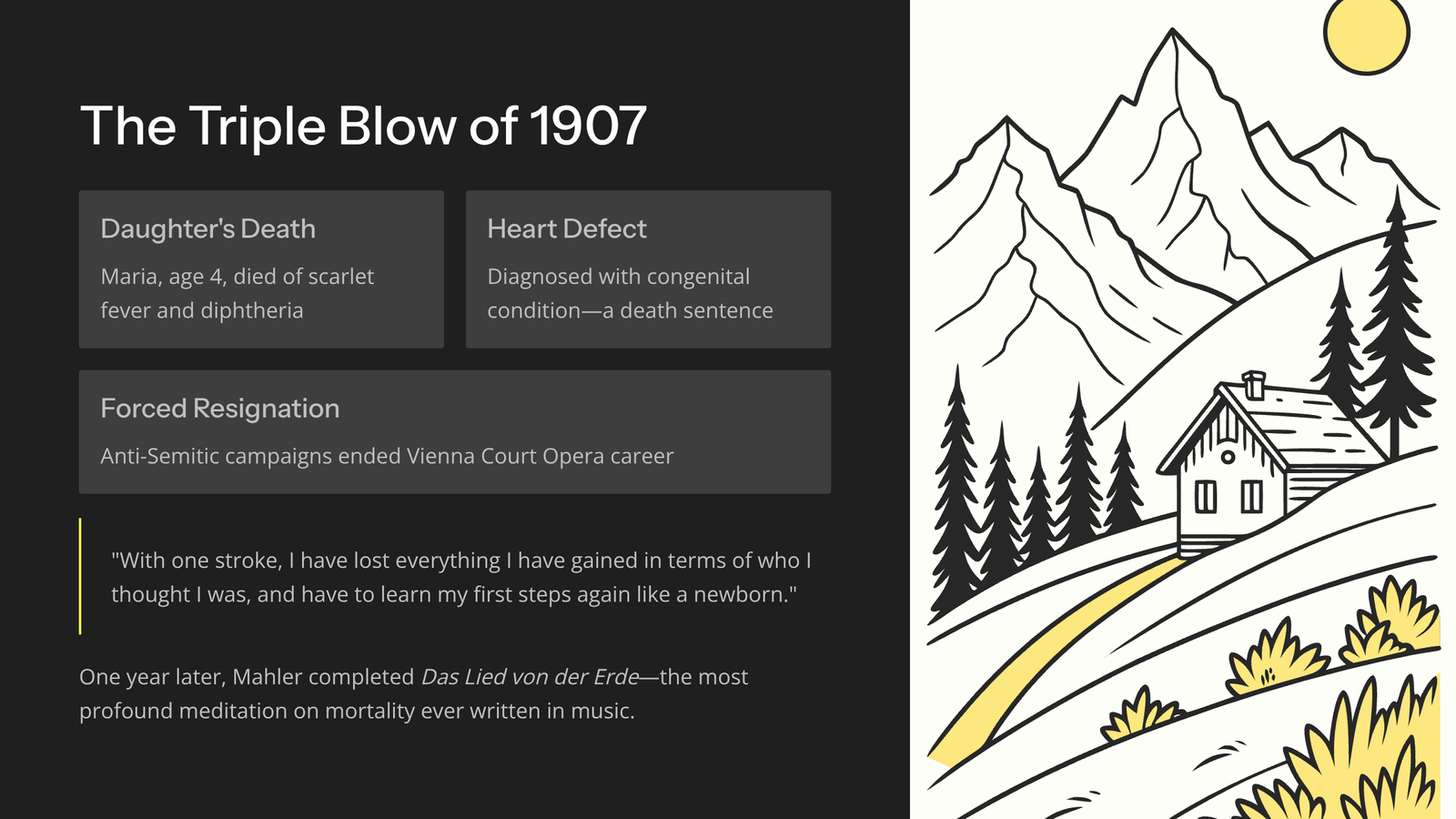

In the summer of 1907, Gustav Mahler lost everything he thought defined him. His four-year-old daughter Maria died of scarlet fever and diphtheria. A doctor diagnosed him with a congenital heart defect that would eventually kill him. Anti-Semitic campaigns forced him to resign from the Vienna Court Opera, the position he had fought his entire life to achieve.

He wrote to his friend Bruno Walter: “With one stroke, I have lost everything I have gained in terms of who I thought I was, and have to learn my first steps again like a newborn.”

One year later, in a small composing hut in the Austrian Alps, Mahler completed what many consider the most profound meditation on mortality ever written in music. The final movement of Das Lied von der Erde, titled “Der Abschied” — The Farewell — stretches across thirty minutes of sound that somehow makes you feel what forever might actually be like. Have you ever wondered what eternity sounds like? Mahler tried to tell us.

The Triple Blow That Changed Everything in Mahler’s Life

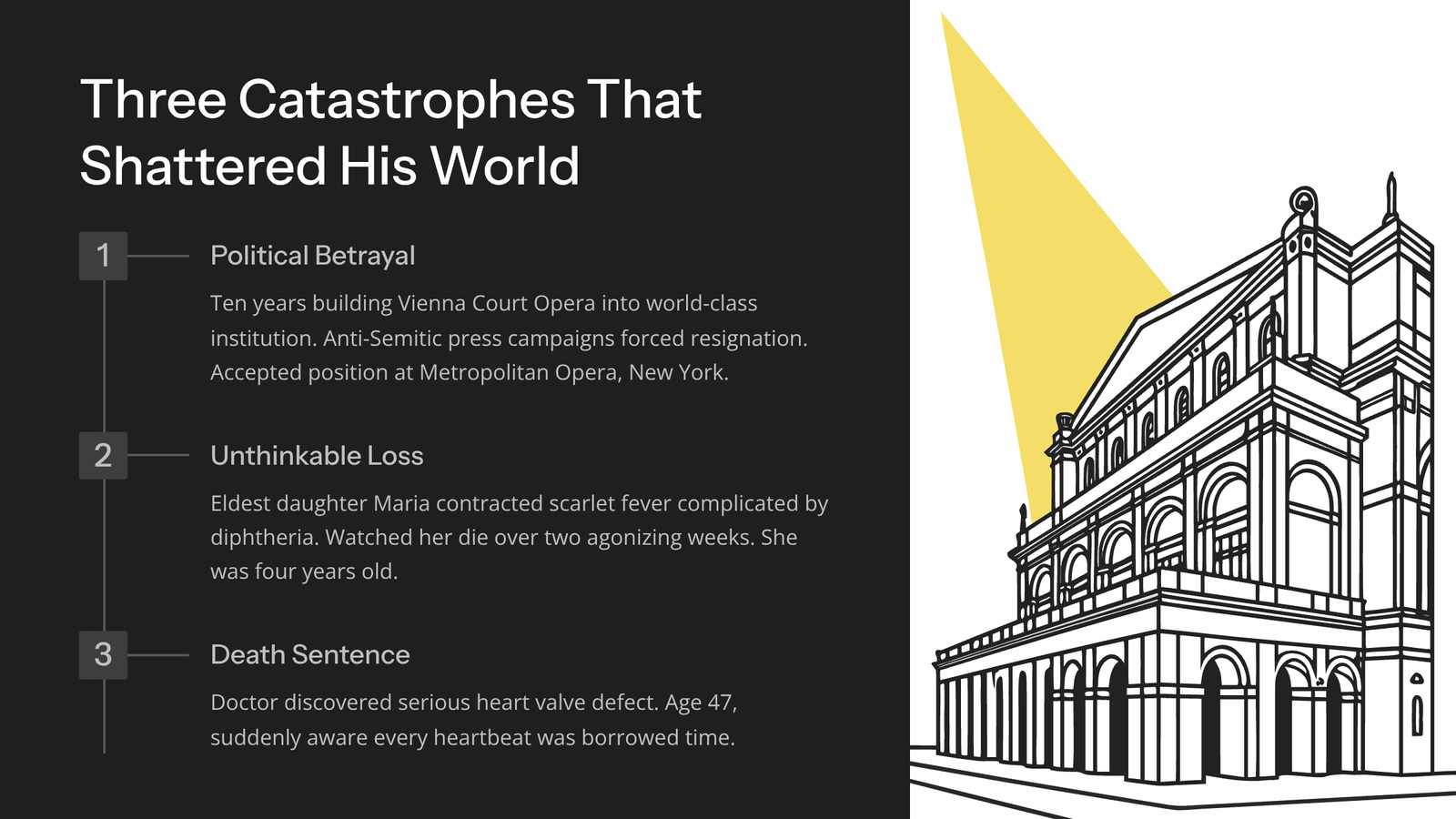

Before we listen to a single note, you need to understand what was happening inside Mahler when he wrote this music. The year 1907 delivered what biographers call his “triple blow” — three catastrophes that arrived in rapid succession and shattered his world.

First came the political betrayal. For ten years, Mahler had transformed the Vienna Court Opera into one of the world’s finest musical institutions. He was brilliant, uncompromising, demanding. He was also Jewish in an increasingly hostile environment. The anti-Semitic press campaigns grew louder until his position became untenable. In 1907, he resigned and accepted a position at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Imagine building your life’s work, only to watch it crumble under the weight of prejudice you never chose.

Then came the unthinkable. His eldest daughter Maria, nicknamed Putzi, contracted scarlet fever complicated by diphtheria. She was four years old. Mahler watched her die over two agonizing weeks. Parents are not supposed to outlive their children. This kind of grief rewrites a person’s internal architecture entirely.

And finally, as if fate had not finished with him, the family doctor examined Mahler during this period and discovered a serious heart valve defect. The diagnosis was essentially a death sentence in slow motion. Mahler was forty-seven years old and suddenly aware that every heartbeat was borrowed time.

How does an artist respond to this kind of devastation? Mahler did what composers do — he wrote music. But the music that emerged was unlike anything he had created before.

Finding Ancient Chinese Wisdom in the Austrian Mountains

The following summer, Mahler retreated to Toblach in the South Tyrolean Dolomites. He rented a small composing hut — a wooden structure barely large enough for a piano and a desk — and began to heal the only way he knew how. Someone, likely his friend Dr. Theobald Pollak, had given him a recently published book of poetry called “Die chinesische Flöte” — The Chinese Flute.

This collection, assembled by Hans Bethge, contained German adaptations of ancient Chinese poems from the Tang Dynasty. The original verses had traveled a remarkable journey — from eighth-century China through French translations by scholars like Judith Gautier, then into German, where Bethge freely reimagined them for Western readers. These were not strict translations but poetic recreations, capturing what Bethge called “the spirit, style, and melody” of the originals.

Something in these ancient words spoke directly to Mahler’s wounded heart. The poems dealt with the transience of beauty, the inevitability of parting, the peculiar comfort of nature’s indifference to human suffering. Tang Dynasty poets like Li Bai, Meng Haoran, and Wang Wei had contemplated mortality twelve centuries earlier, and their wisdom felt startlingly fresh to a man suddenly conscious of his own limited time.

Mahler selected seven poems and set them for orchestra and two vocal soloists — a tenor and either a mezzo-soprano or baritone. He worked with an intensity that surprised even him, completing the sketch of the entire work in just seven or eight weeks. But the final movement, “Der Abschied,” consumed him most completely. It would become the longest single movement he ever wrote, lasting nearly half the entire work’s duration.

Why Mahler Called This a Symphony (But Also Did Not)

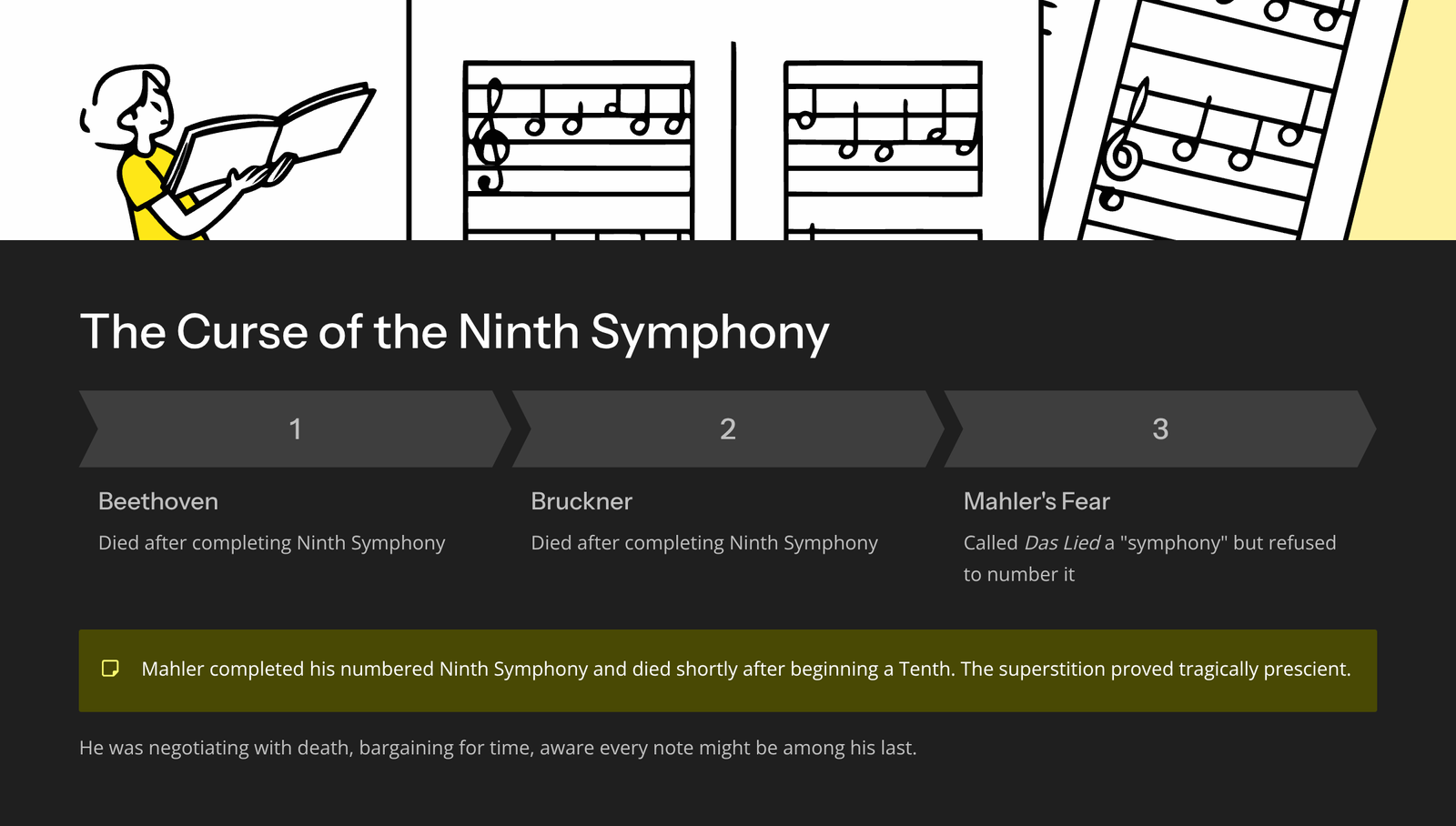

Here is something curious. Mahler subtitled Das Lied von der Erde “A Symphony for Tenor and Alto (or Baritone) Voice and Orchestra.” Yet he never numbered it among his symphonies. After his Eighth Symphony, he jumped directly to the Ninth. Why this strange superstition?

Mahler was deeply aware that both Beethoven and Bruckner had died after completing their ninth symphonies. He feared the number itself. By calling Das Lied von der Erde a “symphony” without giving it a number, he hoped to cheat fate. “It is actually a symphony,” he confided to friends, “but I dare not call it that.”

The superstition proved tragically prescient. Mahler completed his Ninth Symphony — the one that actually bears that number — and died shortly after beginning work on a Tenth. The curse of the ninth claimed him after all, though he had tried so desperately to escape it.

This biographical detail matters because it shows us Mahler’s state of mind while composing. He was negotiating with death, bargaining for more time, fully aware that every note he wrote might be among his last. That consciousness saturates “Der Abschied” completely.

The Two Ancient Poets Speaking Across Time

“Der Abschied” draws its text from two poems by Tang Dynasty poets who were actually friends in real life. The first poet, Meng Haoran, wrote about waiting for a friend at evening. The second, Wang Wei, wrote about that friend’s arrival and departure. Bethge combined these into a single narrative, and Mahler further modified the text, adding his own words at crucial moments.

The story is deceptively simple. A person waits in nature as evening falls. A friend arrives on horseback. They share a final drink together. The friend departs, walking toward some distant homeland. The one who remains watches until the friend disappears into the twilight.

But of course, the story is not simple at all. The “friend” can be understood as life itself, departing. The “homeland” toward which the traveler walks might be death, or it might be some transcendent state beyond our understanding. Mahler transformed a poem about friendship into a meditation on the ultimate farewell that awaits us all.

Most strikingly, Mahler added his own words to the poem’s conclusion. The original Chinese verses end with the departing friend’s journey. Mahler extended this into a vision of eternal renewal: “The beloved earth everywhere blooms in spring and grows green again! Everywhere and forever, the distance shines bright and blue! Forever… forever…”

That word “Ewig” — forever, eternally — repeats seven to nine times at the end, depending on the performance. Mahler wrote it into the fabric of the music itself, making the concept of eternity audible.

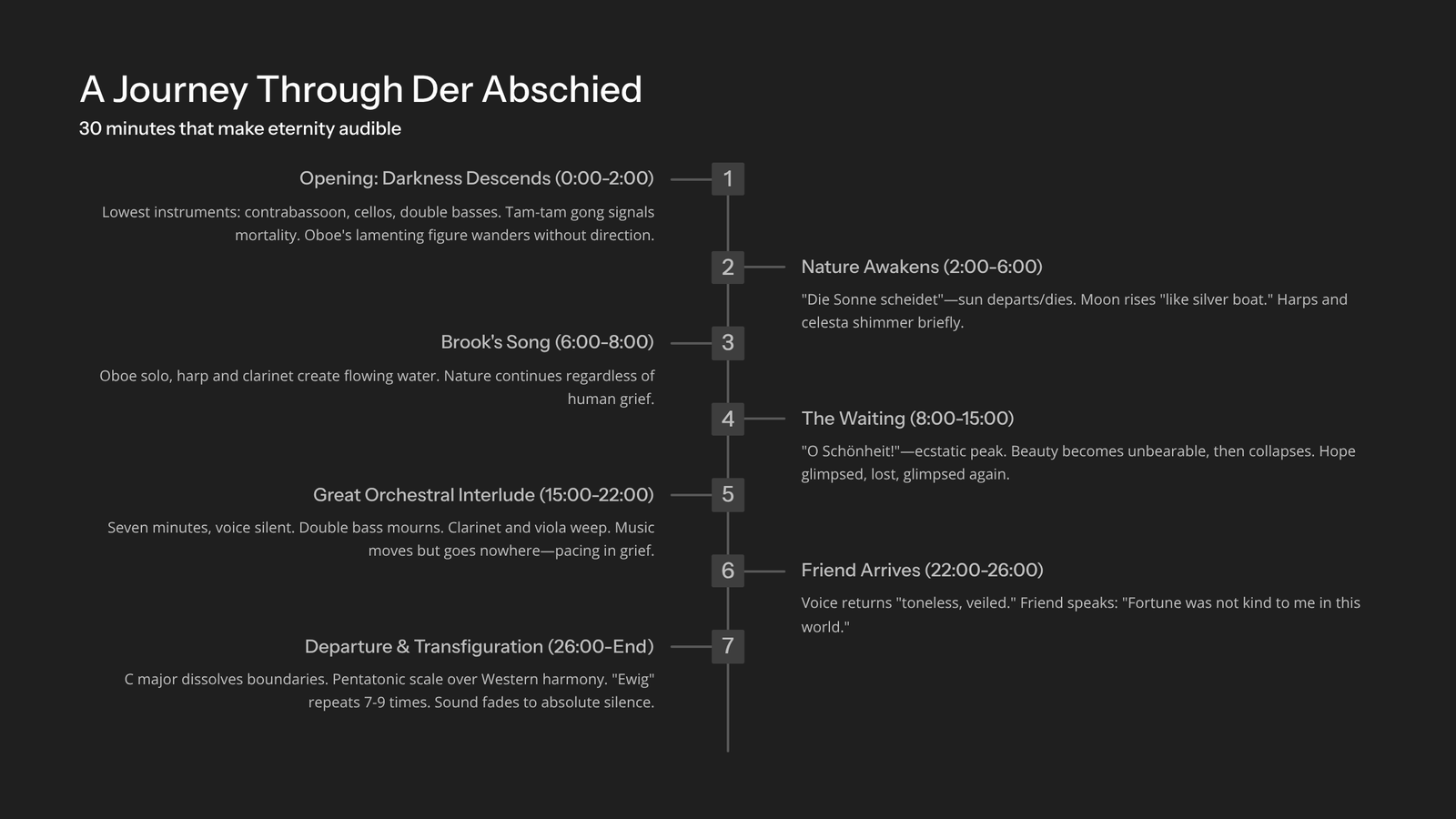

What You Actually Hear: A Guide to Mahler’s Der Abschied

Now let us walk through the music together. I want you to hear what Mahler heard, to feel what he was trying to communicate. Put on headphones if you can. Find thirty uninterrupted minutes. This is not background music — it demands your full attention, and it will reward that attention with something you may never forget.

The Opening: Darkness Descends (0:00 – 2:00)

The movement begins in profound darkness. Mahler marks the tempo “Schwer” — heavy. You hear the lowest instruments of the orchestra: contrabassoon, cellos, double basses, two horns in their lowest register. Mahler specified that the double basses should have a fifth string tuned to low C, extending their range into a subterranean realm.

Then comes the tam-tam — a large gong struck softly but unmistakably. Its sound spreads like a dark stain through the texture. In Mahler’s vocabulary, this instrument always signals something funereal, some encounter with mortality.

Listen for the oboe entering with a lamenting figure, a melody that seems to wander without direction. This is Mahler’s interpretation of Chinese musical aesthetics — music that does not march toward clear goals but instead meanders like a stream, like thought itself.

Nature Awakens in Darkness (2:00 – 6:00)

The voice enters, describing evening falling over mountains and valleys. “Die Sonne scheidet hinter dem Gebirge” — The sun departs behind the mountains. Notice how Mahler treats the word “scheidet” (departs). The same word is used for death in German. The sun is not merely setting; it is dying.

Watch for the moment when the singer describes the moon rising “like a silver boat” across the blue sea of the sky. The orchestration suddenly lightens — harps and celesta create a shimmering effect, and for a moment, beauty breaks through the darkness. But it does not last. It never lasts. That is part of what Mahler is telling us.

The flute plays an important role throughout this movement. Remember that Bethge’s poetry collection was called “The Chinese Flute.” Mahler makes the flute a kind of protagonist, anticipating the vocal lines, commenting on the text, sometimes seeming to know things the singer has not yet discovered.

The Brook’s Song (6:00 – 8:00)

Listen for one of the most touching passages in all of Mahler’s music. The text describes a brook singing through the darkness: “Der Bach singt voller Wohllaut durch das Dunkel.” The oboe plays a quiet solo while the harp and clarinet create a gently rocking triplet rhythm underneath — the sound of water flowing, of nature continuing its business regardless of human grief.

This is one of Mahler’s great insights. Nature does not mourn with us. The brook sings whether we are happy or devastated. There is both comfort and coldness in this realization.

The Waiting (8:00 – 15:00)

Now the singer waits for the friend’s arrival. “Ich stehe hier und harre meines Freundes” — I stand here and wait for my friend. The music builds gradually toward a climax on the words “O Schönheit! O ewigen Liebens — Lebens — trunk’ne Welt!” — O Beauty! O world drunk on eternal loving and living!

This is one of the movement’s ecstatic peaks, a moment when the beauty of existence becomes almost unbearable. Mahler pushes the voice high, the orchestra swells — and then everything collapses. The hope was temporary. The beauty cannot be held. This pattern repeats throughout the movement: transcendence glimpsed, then lost, then glimpsed again.

The Great Orchestral Interlude (15:00 – 22:00)

Here Mahler does something remarkable. For nearly seven minutes, the voice falls silent, and the orchestra alone carries the emotional narrative. This is the heart of the movement, its darkest and most searching passage.

Listen for the double bass playing a mournful melody in its lowest register. Listen for the clarinet and viola taking up a “weeping figure” — a descending line that seems to sob. The music moves but goes nowhere, like someone pacing in grief, covering ground without arriving anywhere.

Mahler marks this section to be played “without pulse” — almost as if the heart has stopped, as if time itself has become uncertain. The cellos insistently circle around single notes, searching for something they cannot find.

This interlude is where many listeners find themselves weeping. Nothing “happens” in any conventional sense. Yet everything happens. Mahler has found a way to make the experience of pure grief audible.

The Friend Arrives (22:00 – 26:00)

The voice returns as the friend finally appears, dismounting from his horse to share a farewell drink. Notice how Mahler marks the singer’s tone: “toneless,” veiled, as if the voice itself is becoming ghostly.

The friend speaks: “Du, mein Freund, mir war auf dieser Welt das Glück nicht hold!” — My friend, fortune was not kind to me in this world! Is this Mahler speaking through the character? Almost certainly. The line feels autobiographical, a confession from a man who had tasted success and sorrow in equal measure.

The Departure and Transfiguration (26:00 – End)

Now comes the extraordinary conclusion. The friend departs, walking toward his homeland. “Ich wandle nach der Heimat, meiner Stätte” — I wander toward my homeland, my dwelling place. The music begins to dissolve, to lose its boundaries.

The key shifts to a luminous C major, but listen carefully — the resolution is never quite complete. Mahler layers a pentatonic scale (the five-note scale associated with Chinese music) over Western harmony, creating a sound that belongs to neither tradition fully. It is music between worlds.

And then: “Die liebe Erde allüberall blüht auf im Lenz und grünt aufs neu!” — The beloved earth everywhere blooms in spring and grows green again! The orchestra responds with one of the most beautiful passages in all music — horns and winds singing of renewal while the strings shimmer below.

Finally, the word “Ewig” begins its repetitions. Forever. Forever. The singer sustains each iteration longer and longer, while the mandolin, harp, and celesta play quietly sustained chords beneath. Mahler instructed performers to take this passage “in the slowest possible tempo, virtually pulseless.”

The voice ends on a high note — technically a D — while the orchestra holds a C major chord with an added A. The two notes do not quite resolve into each other. They hang together in space, neither consonant nor dissonant, simply present. And then the sound fades to absolute silence.

Mahler’s final instruction to performers: hold the silence. Do not break it too quickly. The music has not ended; it has simply become inaudible.

What Makes This Movement So Devastatingly Effective

Why does “Der Abschied” move people so deeply? Part of the answer lies in its structure — or rather, its deliberate lack of conventional structure.

Traditional symphonic movements drive toward conclusions. They create tension and resolve it. They arrive somewhere. “Der Abschied” refuses this trajectory. Its climaxes build and collapse. Its melodies wander without clear destinations. Its ending does not resolve but dissolves.

This mirrors the actual experience of grief and acceptance. We do not “get over” loss in a linear progression. We circle around it, approach it, retreat, approach again. The movement’s seemingly aimless wandering is actually a precise map of how consciousness navigates profound emotion.

Mahler also deploys orchestral color with uncanny psychological accuracy. The mandolin, appearing for only about 25 bars in the entire piece, represents the lute mentioned in the text — the instrument the waiting friend plays. But its thin, plucked sound also suggests fragility, impermanence, the delicacy of all things that exist in time.

The gong appears at moments of finality. The flute suggests both Chinese aesthetics and the breath of life itself. The massed strings at climactic moments create a warmth that feels almost painfully human. Every instrumental choice carries meaning beyond mere sound.

Recommended Recordings for First-Time Mahler Listeners

If you are new to this music, choosing a recording matters enormously. Different conductors reveal different dimensions of the work.

For emotional intensity and narrative clarity, try Kathleen Ferrier’s recording with Bruno Walter conducting the Vienna Philharmonic (1952). Ferrier’s voice — she was dying of cancer during this period, though she may not have known it — carries an authenticity that transcends technique. Many consider it the greatest recording ever made.

For modern sound quality and orchestral detail, Bernard Haitink’s recording with Janet Baker and the Concertgebouw Orchestra (1975) is remarkable. Baker’s final “Ewig” repetitions have been called “hauntingly nostalgic” — she somehow makes the word sound both like an ending and a beginning.

Leonard Bernstein’s recordings (he made several) bring dramatic intensity and personal identification. Bernstein saw Mahler as a kindred spirit, and his performances communicate that spiritual connection.

For a baritone version, try Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with any of his recorded collaborators. The male voice brings a different quality — perhaps more existential, less intimate, but equally valid.

Listening Tips for Der Abschied: Practical Suggestions

Here are some specific suggestions for engaging with this music:

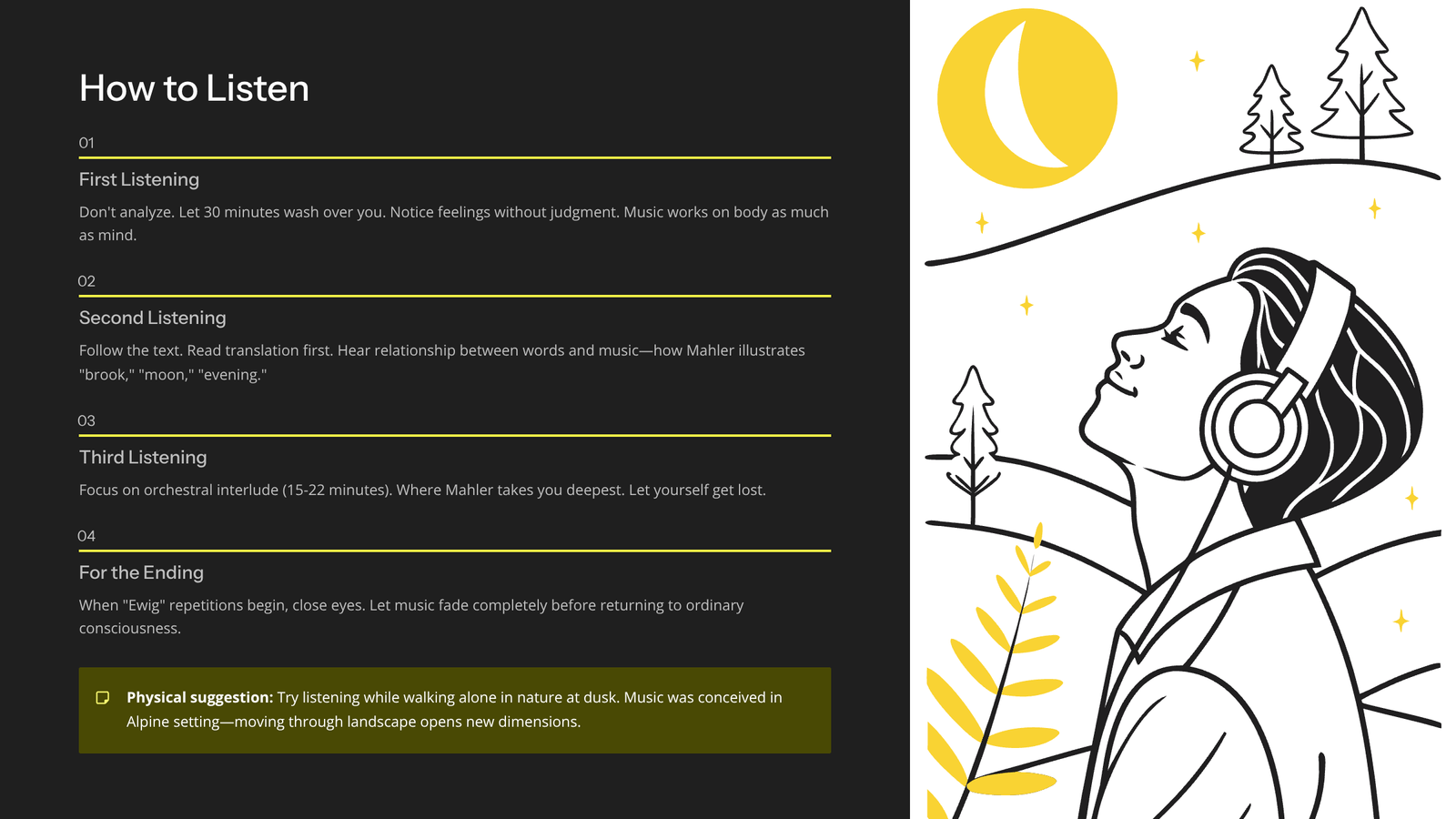

First listening: Do not try to follow the structure. Just let the thirty minutes wash over you. Notice what feelings arise without trying to analyze them. This music works on the body as much as the mind.

Second listening: Follow the text. Read a translation before you begin, then try to hear the relationship between words and music. Notice how Mahler illustrates “brook” and “moon” and “evening” in sound.

Third listening: Focus on the orchestral interlude (approximately 15-22 minutes in most performances). This is where Mahler takes you deepest. Let yourself get lost in it.

For the ending: When you hear the “Ewig” repetitions begin, close your eyes. Let the music fade completely before returning to ordinary consciousness. Mahler built a transition from sound to silence into the piece itself. Honor it.

Physical suggestion: Try listening while walking alone in nature, particularly at dusk. The music was conceived in an Alpine setting, and something about moving through landscape while hearing it opens new dimensions of understanding.

What This Music Might Change in You

After the premiere of Das Lied von der Erde in November 1911 — six months after Mahler’s death — the composer Anton Webern wrote that the experience was “unfathomably beautiful.” That phrase captures something important. This music is not merely beautiful in the ordinary sense. It is beautiful in a way that exceeds comprehension.

Mahler did not live to hear his farewell performed. He died in Vienna in May 1911, his heart finally giving out, just as the doctors had predicted four years earlier. His final word, allegedly, was “Mozart.” He was fifty years old.

But the music remains, waiting for each new listener to discover it. And here is what I find most remarkable: despite being about death and parting, “Der Abschied” does not leave you feeling hopeless. It leaves you feeling — what, exactly? Cleansed, perhaps. Or expanded. Or simply more aware of what it means to be alive for a limited time in a world of overwhelming beauty.

The beloved earth blooms in spring. The distance shines blue. Forever. Forever.

Mahler’s last message was not despair. It was attention — attention to the world that remains when we are gone, attention to the love that outlasts individual lives, attention to the fact of existing at all.

Listen to “Der Abschied” when you are ready for it. And when you hear those final “Ewig” repetitions fade into silence, you may find that something in you has been permanently rearranged. That is what great music does. It changes the listener.

Forever.