📑 Table of Contents

Have you ever woken from a beautiful dream, only to feel an inexplicable chill run down your spine? That sudden shift from warmth to unease—Frédéric Chopin captured this exact sensation in a single piece of music nearly two centuries ago.

The Nocturne in B major, Op. 32 No. 1 begins as one of Chopin’s most serene creations. For several minutes, you float through gentle melodies that feel like moonlight on still water. Then, without warning, everything changes. The music fractures. A deep, ominous rumble emerges from the bass. And suddenly, you’re no longer dreaming—you’re awake, and something is terribly wrong.

This is Chopin’s most mysterious nocturne, and tonight, I want to share its secrets with you.

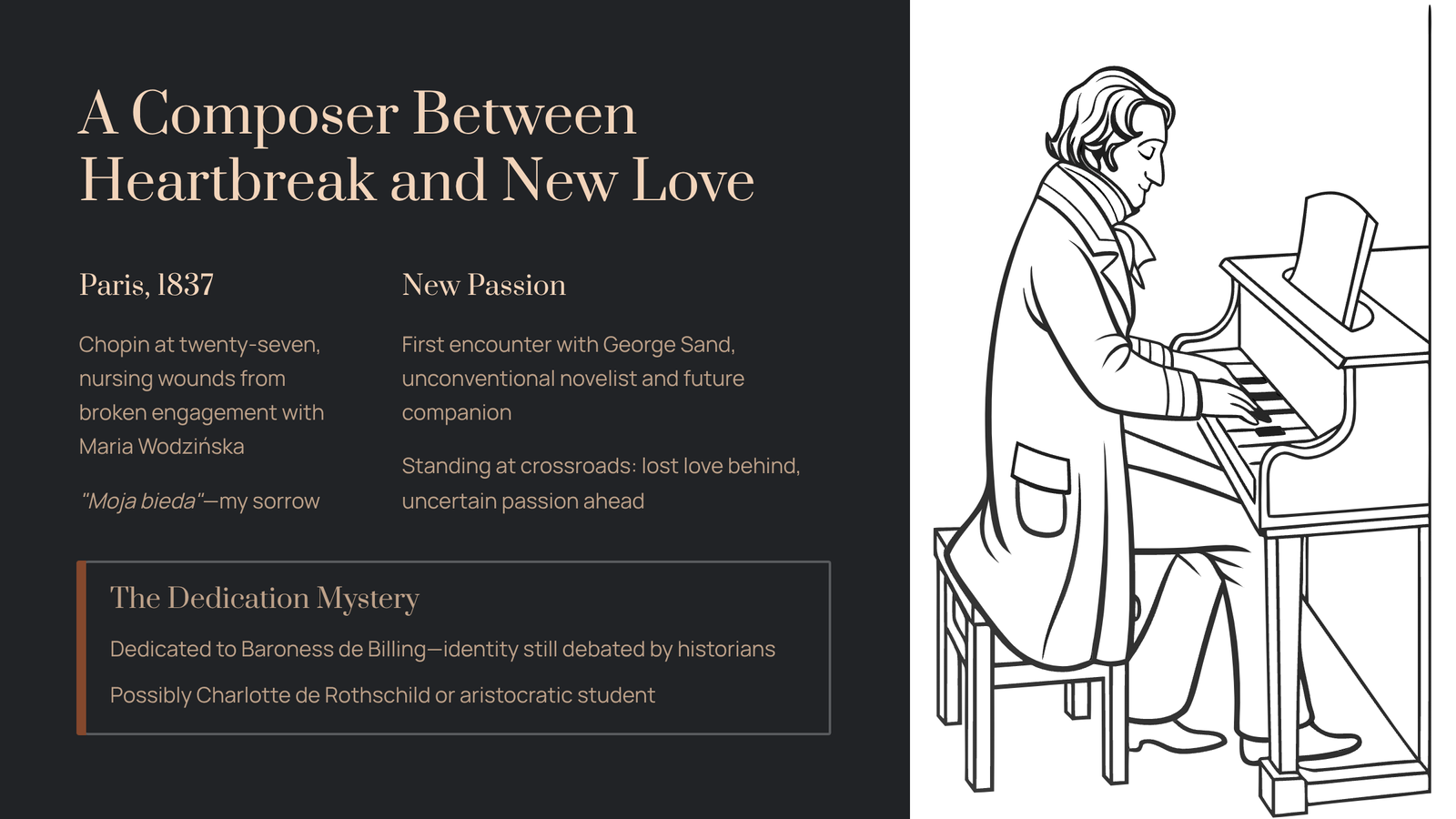

A Composer Between Heartbreak and New Love

Paris, 1837. Chopin was twenty-seven years old, nursing wounds from a broken engagement with Maria Wodzińska. The letters she returned to him, tied with ribbon, he would keep in an envelope marked “Moja bieda”—my sorrow.

Yet this was also the year he first encountered George Sand, the unconventional novelist who would become his companion for the next decade. Chopin stood at a crossroads: the pain of lost love behind him, uncertain passion ahead.

From this emotional twilight, he composed the Op. 32 Nocturnes. He dedicated the first one to the Baroness de Billing, a figure so obscure that historians still debate her identity. Some whisper she might have been a pseudonym for Charlotte de Rothschild. Others believe she was simply one of Chopin’s many aristocratic students in the Parisian salons.

What we know for certain is that Chopin created something unusual here—a nocturne that refuses to follow the rules.

Why This Nocturne Breaks the Mold

Most of Chopin’s nocturnes follow a familiar pattern: a lyrical A section, a contrasting middle, then a return to the opening theme. Comfortable. Predictable. Beautiful.

Op. 32 No. 1 abandons this structure entirely. Music theorist Theodor Kullak described it as “alternating strophes”—verses that flow into each other without clear boundaries, like a poem where the stanzas blur together in candlelight.

The piece begins in B major, a key often associated with tenderness and intimacy. The right hand sings a melody rich with ornamental grace notes, borrowing from the bel canto tradition of Italian opera. The left hand doesn’t cascade in dramatic arpeggios like in other nocturnes; instead, it offers gentle, supportive chords—a quiet heartbeat beneath the dreaming voice above.

And then there’s the ending.

The Coda That Changed Everything

Around the four-minute mark, the music does something almost unprecedented in Chopin’s nocturne repertoire. The flowing melody stops. The tempo slows to Adagio. And a passage marked recitativo appears—a technique borrowed from opera, where singers speak rather than sing.

This is the piano trying to say something.

In the bass, a low trembling begins. Critics have called it many things: a drum roll, distant thunder, the tolling of a clock. Theodor Kullak heard it as “a clock striking the hour, or someone knocking at the door—ending all reverie.”

James Huneker, the great American music critic, gave it an even more dramatic name: “the drum-beat of tragedy.”

The music that was floating in peaceful B major suddenly plunges into B minor. The dream doesn’t fade gently into waking—it shatters. The final chord lands not with resolution, but with a question mark.

The Mystery Pianists Still Debate

Here’s where things get fascinating for music detectives.

In Chopin’s manuscript, that final chord is clearly written as B minor—a dark, unresolved ending that leaves the listener suspended in uncertainty. This is how most editions print it. This is how many pianists perform it.

But Arthur Rubinstein, perhaps the most celebrated Chopin interpreter of the twentieth century, played the final chord as B major.

Why would a master like Rubinstein contradict the score? He was applying a centuries-old technique called tierce de Picardie—ending a minor-key passage with a major chord, offering a glimmer of light after darkness. In Rubinstein’s reading, the dream doesn’t shatter; it transforms. The dreamer wakes, yes, but finds peace rather than terror.

Which ending is “correct”? Both have their defenders. The minor ending honors Chopin’s written intentions and delivers maximum emotional impact. The major ending offers redemption, suggesting that whatever knocked at the door was not destruction but awakening.

When you listen, pay attention to which version your pianist chooses. It reveals everything about how they understand this music.

How to Listen: A Guided Journey

0:00 – 1:30 | The Dream Begins

Let the opening wash over you without analysis. Notice how Chopin gently pushes and pulls the tempo—slight hesitations (ritardando) followed by returns to pace (a tempo). This is rubato, the art of “stolen time” that makes Chopin’s music breathe. The melody never quite moves in strict rhythm; it floats, the way thoughts drift just before sleep.

1:30 – 4:00 | Deepening

The music continues without dramatic contrast. New melodic material appears, but it maintains the same dreamlike quality. Around the three-minute mark, listen for diminished seventh chords—those slightly dissonant harmonies that create a subtle sense of unease beneath the surface beauty. Something is stirring in the depths.

4:00 – End | The Awakening

This is where you must listen most carefully. The recitativo passage arrives like a voice breaking through fog. The left hand’s low rumble emerges—fate knocking, a clock striking, thunder on the horizon.

Notice how abruptly the piece ends. There is no gentle fade, no lingering farewell. Chopin cuts the music off like waking from a dream mid-sentence.

Recommended Recordings

For the B minor ending (Chopin’s original): Seek out recordings by Maurizio Pollini or Krystian Zimerman. They honor the score’s darkness with unflinching clarity.

For the B major ending (Rubinstein’s interpretation): Arthur Rubinstein’s own recordings remain definitive. His warm tone transforms the ending into something almost healing.

For a modern perspective: Seong-Jin Cho and Jan Lisiecki offer interpretations that balance technical precision with emotional depth, each making their own choice about that final, fateful chord.

Final Thoughts

What makes the Nocturne Op. 32 No. 1 unforgettable isn’t its beautiful melodies—Chopin wrote many of those. It’s the courage to end a dream with a question rather than an answer.

In 1837, standing between his past and future, Chopin composed a nocturne that asks: What happens when peace is interrupted? When the knock comes at the door? When we wake and don’t know if we’re safe or in danger?

Nearly two hundred years later, we still don’t have the answer. And perhaps that’s precisely the point.

The next time you can’t sleep, put this nocturne on. Let the first four minutes comfort you. And when that bass rumble begins, ask yourself: Would you rather wake into light, or into shadow?

Chopin left both doors open. The choice is yours.