Table of Contents

A Poem Encountered in Silent Time

Some music takes residence in the deepest corners of our hearts from the very first note. Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, 3rd Movement is precisely such a piece. Though marked “Poco Allegretto,” this music is far removed from its literal meaning of “a little fast.” Instead, it moves slowly, very carefully caressing our souls.

The moment the first notes flow forth, it feels like late autumn sunlight filtering through a window. As Clara Schumann so poetically described this movement, it is “a gray pearl, but one dipped in tears of melancholy” – beautiful yet tinged with an ineffable sadness that brushes against the heart.

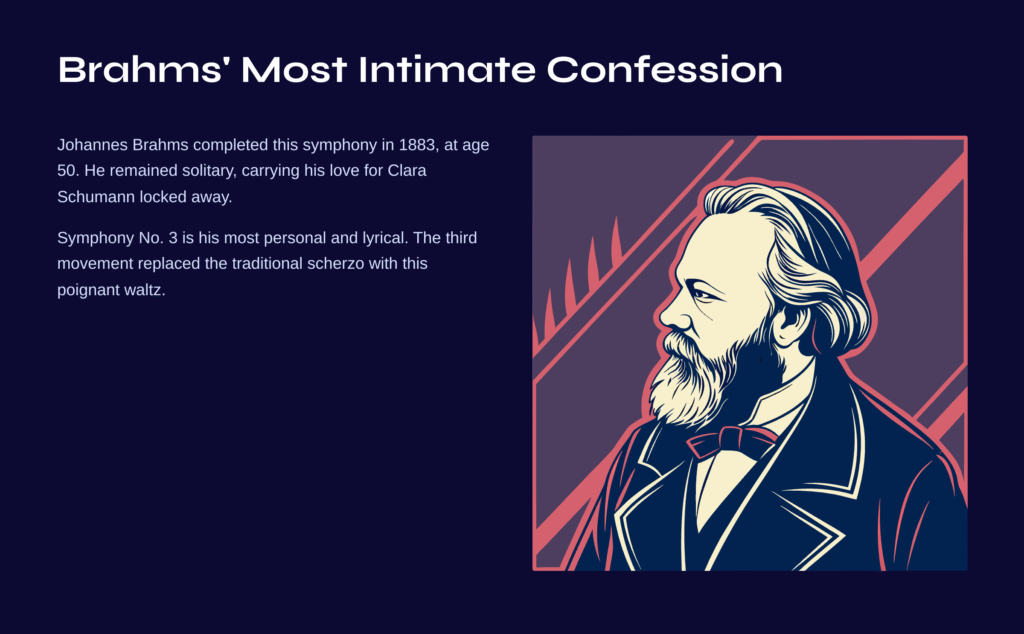

Brahms’ Most Intimate Confession

Johannes Brahms completed this symphony in 1883, at the age of 50. Though already recognized as a master of German Romantic music, he remained a solitary soul. Never having married, he carried his deep love for Clara Schumann locked away in his heart.

Symphony No. 3 is considered the most personal and lyrical of Brahms’ four symphonies. The third movement, in particular, was revolutionary for its time – replacing the traditional scherzo with this poignant waltz. The shift from the symphony’s overall F major to c minor in this movement is deeply significant, like suddenly discovering shadows within bright sunlight.

The gentle 3/8 rhythm takes the form of a waltz, but not the glittering dance of a ballroom – rather, it resembles a solitary dance performed in one’s private chamber. Through this movement, Brahms carefully unveils the emotions hidden in the deepest recesses of his inner world.

From Cello’s Confession to Horn’s Soliloquy – A Sonic Journey Through the Movement

First Section: The Cello’s Poignant Confession

The piece begins with the cello’s low, deep voice – a melody that feels like sharing a long-held secret for the first time. This principal theme moves in a descending pattern, conveying a sense of letting go, of resignation.

When the cello begins its narrative, the clarinet gently supports with harmonies, like a friend quietly listening nearby. In this moment, the orchestra forgets its massive forces and becomes as intimate as chamber music. Indeed, Brahms omitted the contrabassoon, F horns, trumpets, and timpani from this movement, and excluded trombones as well. This restraint paradoxically creates deeper emotional impact.

Second Section: The Fragrance of Romani Music

In the middle section, the woodwinds take the lead. Here, Brahms borrows subtle colors from Romani (Gypsy) music. The sliding phrases of the woodwinds and the gentle responses from the strings create the impression of a musical conversation.

This section bears a slightly brighter, more hopeful character than the opening theme, though it’s not entirely joyful. It’s like recalling beautiful moments within sad memories – painting happiness that exists only in dreams.

Third Section: The Horn’s Majestic Soliloquy

The opening theme returns, but now the horn takes center stage. The horn, a brass instrument with woodwind-like softness, is uniquely suited to this role. Brahms utilizes this instrument’s characteristics perfectly, making the melody sound like a voice of recollection from afar.

This horn solo ranks among the most celebrated passages in classical music history. While technically challenging for horn players, it represents a moment of supreme musical emotion. It feels as though someone from across time is speaking directly to us.

The oboe then takes up the same melody, its pastoral and pure tone contrasting beautifully with the horn’s grandeur, creating yet another layer of emotion. Finally, the violins conclude the movement with a sense of peaceful acceptance.

Moments When Time Seems to Stand Still

Each time I listen to this piece, I’m struck by how differently time flows. Though lasting only 5-6 minutes, it leaves the impression of having read a lengthy novel. Brahms compressed countless human emotions into this brief span.

Sometimes this music feels like Brahms’ autobiography – his love for Clara, his artistic solitude, his longing and resignation, and the nobility of bearing all these feelings while living. Every note seems weighted with life’s gravity.

The poignancy when the cello first presents the theme is particularly moving – it has the sincerity of someone finally sharing a long-held secret. And when the horn takes up this story, elevating it to a more majestic, universal dimension, the emotion becomes almost indescribable.

A Small Guide for Deeper Listening

To truly appreciate this piece, focus on several key points. First, notice how the clarinet supports the cello when it presents the theme – it’s not mere accompaniment, but rather like a understanding friend offering comfort.

During the horn solo, concentrate on the sense of distance and proximity in the sound. Brahms uses the horn to create a voice that seems to transcend time and space. When listening to this section, close your eyes and imagine what landscapes come to mind.

When choosing recordings, I recommend performances that don’t rush the tempo. This piece reveals its true character when unhurried. Recordings by Karajan or Bernstein make excellent starting points. If the music touches you on first hearing, listen repeatedly – you’ll discover new facets with each experience.

Music’s Eternal Consolation

Brahms’ Symphony No. 3, 3rd Movement perfectly demonstrates how music can transcend time. Created over 140 years ago, it still speaks to us as if telling our own story – of love’s pain, loneliness’s weight, and the human strength to endure it all.

Like Clara Schumann’s description, this piece truly is a “gray pearl dipped in tears of melancholy.” Not flashy, but the depth and truth contained within seems more valuable than any precious stone. Through this music, Brahms seems to tell us that while life can be heavy and lonely, we can still find beauty within it – and such beauty is precisely why we live.

When the music ends, we somehow feel comforted. There’s a sense of not being alone, a warmth that someone understands our hearts. Isn’t this the true power of music?

Perfect Follow-up: Grieg’s “Morning Mood” (from Peer Gynt Suite)

Having fully savored Brahms’ gray pearl of melancholy, it’s time to let another piece guide our hearts to different landscapes. Edvard Grieg’s “Morning Mood” provides the perfect contrast to Brahms’ introspective meditation.

This piece, seemingly capturing the very air of Norwegian dawn, begins with the flute’s pure, clear melody. Where Brahms’ cello represented memories rising from deep places, Grieg’s flute is like light descending from on high. It feels like a troubled heart gradually meeting the brightening dawn after a long, dark night.

The warmth when the oboe takes up the flute’s melody is particularly striking – a different kind of emotion from the majestic resonance of Brahms’ horn solo. It’s lighter, more hopeful, yet filled with natural joy.

Listening to these two pieces in sequence creates a journey from long night to dawn’s arrival. The moment when Grieg’s clear hope follows Brahms’ deep contemplation reveals more vividly how music can heal our hearts.