Table of Contents

Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 9 in C Major – II. Andante

Have you ever witnessed a stage where the actors don’t just change—they transform the entire atmosphere with their presence? Where the arrival of new voices doesn’t simply add to the conversation, but fundamentally alters the color of the air itself?

This is exactly what happens in the Andante movement of Mendelssohn’s String Symphony No. 9. And here’s what makes it extraordinary: this wasn’t written by a seasoned master reflecting on decades of experience. This was homework. A counterpoint assignment handed to a 14-year-old boy by his strict teacher, Carl Zelter, in March of 1823.

The Assignment That Became a Revelation

Picture this: young Felix Mendelssohn, barely into his teenage years, sitting with music paper spread before him. His family had just returned from a summer journey through Switzerland, where the mountains and valleys had left their impressions on his imagination. Now, his teacher demanded something rigorous—a demonstration of Bach’s counterpoint principles, the architectural rules of voice-leading that had governed music for over a century.

But Mendelssohn didn’t just complete the assignment. He discovered something.

What if, instead of treating all the string instruments as a single unified voice, you could divide them into two distinct worlds? What if you could create a conversation not just between melodies, but between entire sonic universes?

Two Worlds, One Movement

The Andante movement unfolds in E major—a key that brings a gentle brightness after the opening movement’s C major foundation. But it’s not the key that defines this music. It’s the radical way Mendelssohn deploys his forces across 169 measures.

The first section begins with something almost impossibly delicate: four solo violins, and nothing else. No violas providing cushion underneath. No cellos anchoring the harmony. Just four voices in the upper register, speaking to each other with the intimacy of a late-night conversation. Their lines interweave with baroque precision, yet there’s something distinctly romantic in their expressiveness—a tension between old rules and new feelings.

The sound is transparent. Crystalline. You can hear every voice distinctly, following each melodic thread as it passes from violin to violin. It’s like watching light refract through ice.

Then comes the transformation.

The violins fall silent, and suddenly we’re in a completely different acoustic space. Now it’s the violas, cellos, and double basses alone—the darker, warmer voices from the lower end of the string family. This orchestration is almost unheard of in the classical tradition. Since the Baroque era, composers had largely avoided giving extended passages solely to the lower strings without the brilliance of violins to balance them.

But Mendelssohn understood something: contrast creates meaning. By removing the violins entirely, he doesn’t just change the texture—he changes the emotional gravity of the music. The same melodic ideas that felt light and conversational in the violin section now take on weight, depth, a more introspective character.

It’s not about one being better than the other. It’s about the dialogue between them.

The Architecture of Light and Shadow

What Mendelssohn learned from Bach wasn’t just counterpoint technique—it was the principle of clarity through distinction. Baroque music often worked by clearly separating different musical forces, allowing each its moment to speak. Think of the ritornello form in a Bach concerto, where the full orchestra and the soloist take turns like actors on a stage.

Mendelssohn applies this principle not to themes, but to timbre itself. The outer sections with their solo violins represent light—bright, elevated, almost celestial. The middle section with its lower strings represents shadow—warmer, earthbound, reflective. The movement becomes a meditation on how the same musical ideas can mean different things depending on who speaks them.

There’s a moment about midway through when the shift happens. You’ll hear the violins gradually receding, their final notes hanging in the air like the last light before dusk. Then the violas enter, and suddenly you’re aware of how much acoustic space the violins had occupied. The absence creates its own kind of presence.

Later, when the violins return, it doesn’t feel like a simple repeat. It feels like a resolution—like returning home after a long walk and seeing familiar rooms with new eyes.

What to Listen For: A Personal Roadmap

Let me suggest a few specific moments that might help you unlock this music:

First, follow the handoffs. In the opening violin section, pay attention to how a melodic phrase will begin in one violin and be picked up by another. It’s like watching a relay race where the baton is passed with perfect grace. The counterpoint isn’t just mathematical—it’s gestural, almost physical.

Second, notice the shift in acoustic perspective. When the lower strings take over, close your eyes and feel how the music seems to move from head height down to chest level. The same harmonic progressions that felt airy and distant in the violins now feel intimate and present in the violas and cellos.

Third, listen for the independence of each voice. Even when all the instruments in a section are playing together, each has its own melodic line. Try following just one instrument—pick the first violin, or the cello—and trace its journey through the movement. You’ll discover a complete musical narrative that exists alongside, and in conversation with, all the others.

Finally, pay attention to the silences. Between the sections, there are brief moments where one group finishes and the other hasn’t quite begun. These threshold moments, these breaths between worlds, are where the architecture reveals itself.

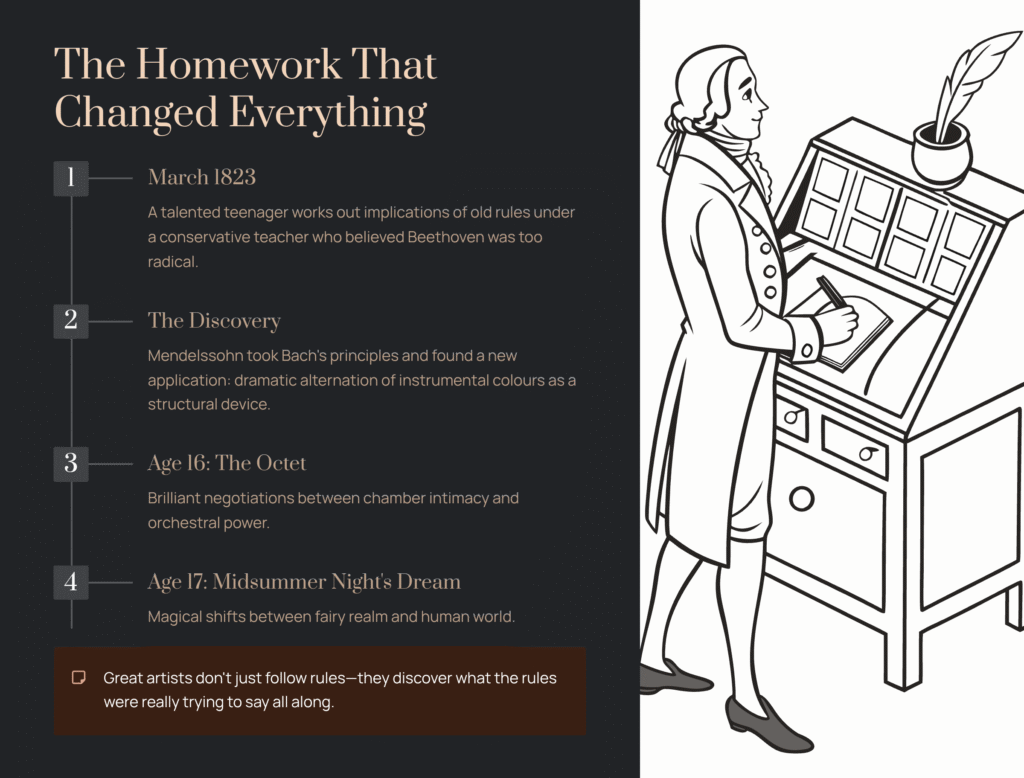

The Homework That Changed Everything

When you listen to this Andante, remember: this was an exercise. A talented teenager working out the implications of old rules under the watchful eye of a conservative teacher who believed the modern music of Beethoven was too radical, too undisciplined.

But great artists don’t just follow rules—they discover what the rules were really trying to say all along.

Mendelssohn took Bach’s principles of clear voice-leading and textural contrast and found a new application: the dramatic alternation of instrumental colors as a structural device. This idea would echo through his later masterpieces—the Octet he’d write at 16, with its brilliant negotiations between chamber intimacy and orchestral power; the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture at 17, with its magical shifts between fairy realm and human world.

But it started here, in a homework assignment, with a simple question: what if the architecture of sound could be about more than just notes? What if it could be about the very nature of musical conversation?

Listening Recommendations

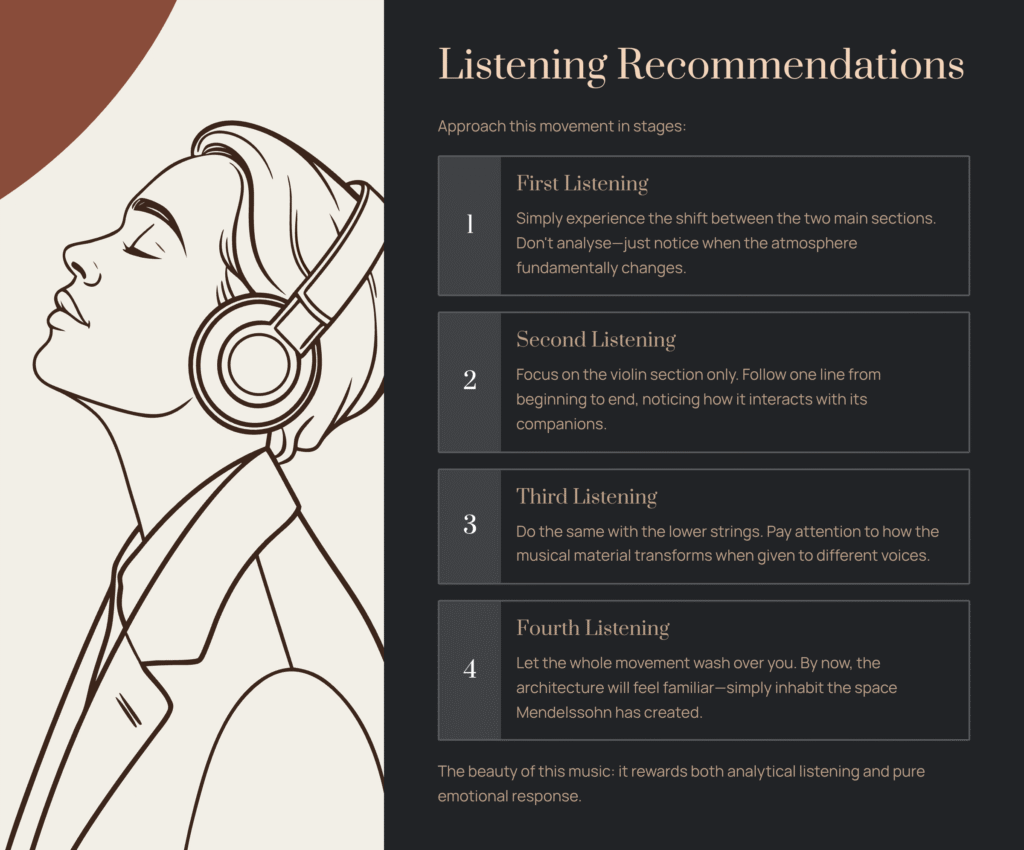

I’d suggest approaching this movement in stages:

First listening: Simply experience the shift between the two main sections. Don’t try to analyze—just notice when the atmosphere fundamentally changes.

Second listening: Focus on the violin section only. Follow one line from beginning to end, noticing how it interacts with its companions.

Third listening: Do the same with the lower strings. Pay attention to how the musical material transforms when given to different voices.

Fourth listening: Let the whole movement wash over you. By now, the architecture will feel familiar, and you can simply inhabit the space Mendelssohn has created.

The beauty of this music is that it rewards both analytical listening and pure emotional response. You can appreciate the craftsmanship or simply let yourself be moved by the gentle dialogue between light and shadow, height and depth, question and answer.

A Quiet Legacy

The Andante movement of Mendelssohn’s String Symphony No. 9 is not a showpiece. It won’t dazzle you with virtuosity or overwhelm you with dramatic gesture. Instead, it offers something more subtle: a perfect balance between intellectual rigor and emotional sensitivity, between historical awareness and personal expression.

It reminds us that sometimes the most profound innovations come not from rejecting tradition, but from understanding it so deeply that you can see possibilities others missed. A 14-year-old boy, working through a counterpoint exercise, discovered that the space between voices could be as meaningful as the voices themselves.

And perhaps that’s the real lesson here—that music, like all conversation, is as much about the listening as the speaking. About creating space for different voices to be heard in their full distinctiveness, and trusting that their dialogue will create something greater than any single voice could achieve alone.

The next time you listen, pay attention to those moments of transition. Notice what it feels like when one world recedes and another emerges. Feel the shape of the silence between them.

That’s where Mendelssohn hid his secret: not in the notes themselves, but in the spaces between, where transformation happens and new understanding begins.