Table of Contents

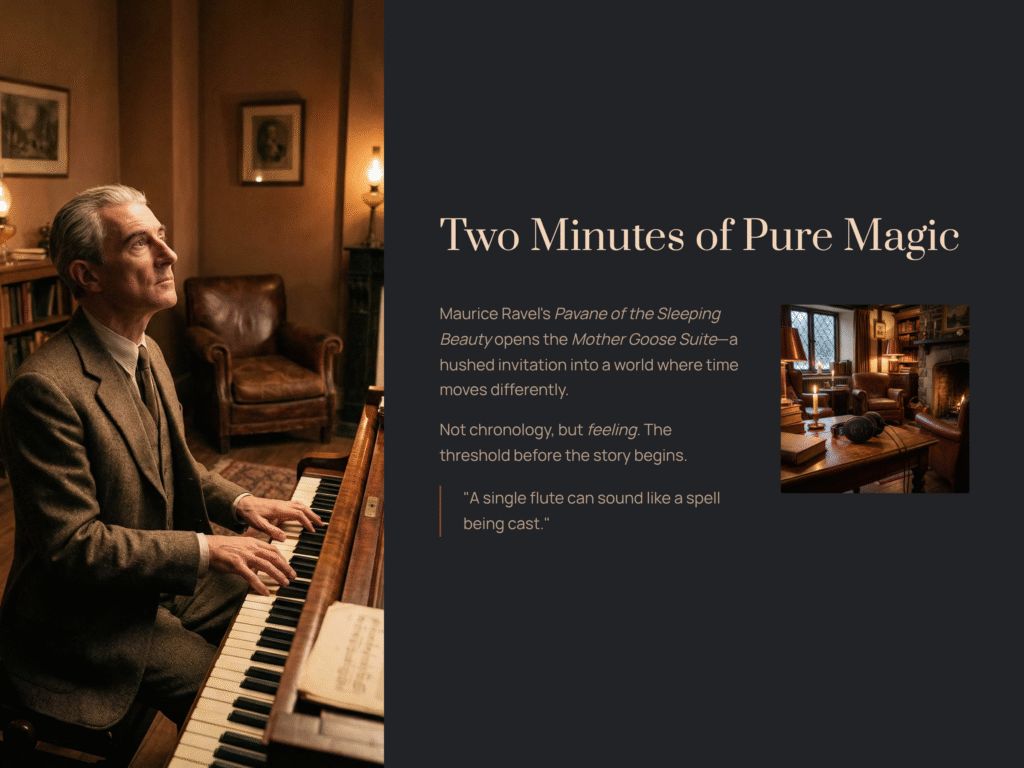

What if I told you that one of the most exquisite moments in orchestral music lasts barely two minutes? That in those fleeting seconds, Maurice Ravel managed to capture the essence of a sleeping princess, a fairy’s tenderness, and the suspended breath of a fairy tale frozen in time?

This is the Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty, the opening movement of Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite. You might wonder why it’s placed first among five fairy tales. The answer lies not in chronology but in feeling—this is the threshold, the hushed invitation into a world where time moves differently, where a single flute can sound like a spell being cast.

I first heard this piece on a winter evening, headphones on, eyes closed. The opening notes arrived like snowflakes—soft, deliberate, impossibly delicate. I didn’t know then that I was listening to one of music’s greatest magicians at work, a composer who could paint with sound the way Monet painted with light.

The Story Behind the Spell

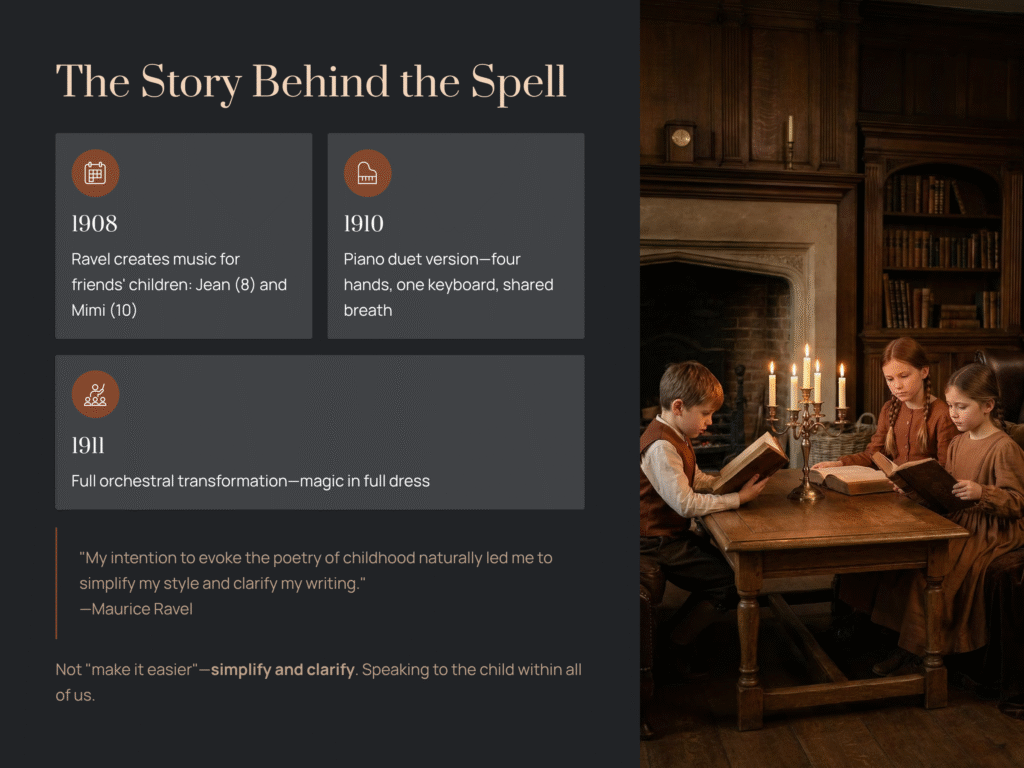

In 1908, Ravel had no children of his own. But he had something perhaps rarer: a genuine understanding of how a child’s imagination works. When his dear friends Cipa and Ida Godebski asked him to create something for their children—Jean, age eight, and Mimi, age ten—Ravel didn’t condescend. He didn’t simplify. Instead, he wrote something he himself described with striking clarity:

“My intention to evoke the poetry of childhood naturally led me to simplify my style and clarify my writing.”

Notice what he didn’t say. He didn’t say “make it easier” or “dumb it down.” He said simplify and clarify—which is entirely different. It’s the difference between talking down to a child and speaking to the child within all of us, that part that still believes in magic, that can be transported by a melody.

The piece emerged first as a piano duet in 1910, four hands sharing a single keyboard, two people breathing together over the keys. Then, in 1911, Ravel gave it its full orchestral dress—and what a transformation that was.

The Ancient Dance Reborn

A pavane is a court dance from the 16th century, stately and slow, the kind of thing you’d see in Spanish palaces where every step was measured, every gesture carried weight. Ravel chose this form deliberately, not to show off his historical knowledge but because a pavane has this quality of suspended animation—it moves forward while seeming to stand still, just like a sleeping princess trapped in enchantment.

But here’s where Ravel’s genius surfaces: he doesn’t recreate a Renaissance dance. He remembers it through the haze of centuries, through a fairy tale filter, through a child’s sense of “once upon a time.” The result is music that feels both ancient and utterly fresh, like finding a medieval tapestry that somehow still smells of spring flowers.

The Sound of Watching Someone Sleep

Let me walk you through what you’ll hear, but not in the clinical way of a textbook. Think of it as someone describing a dream while still half inside it.

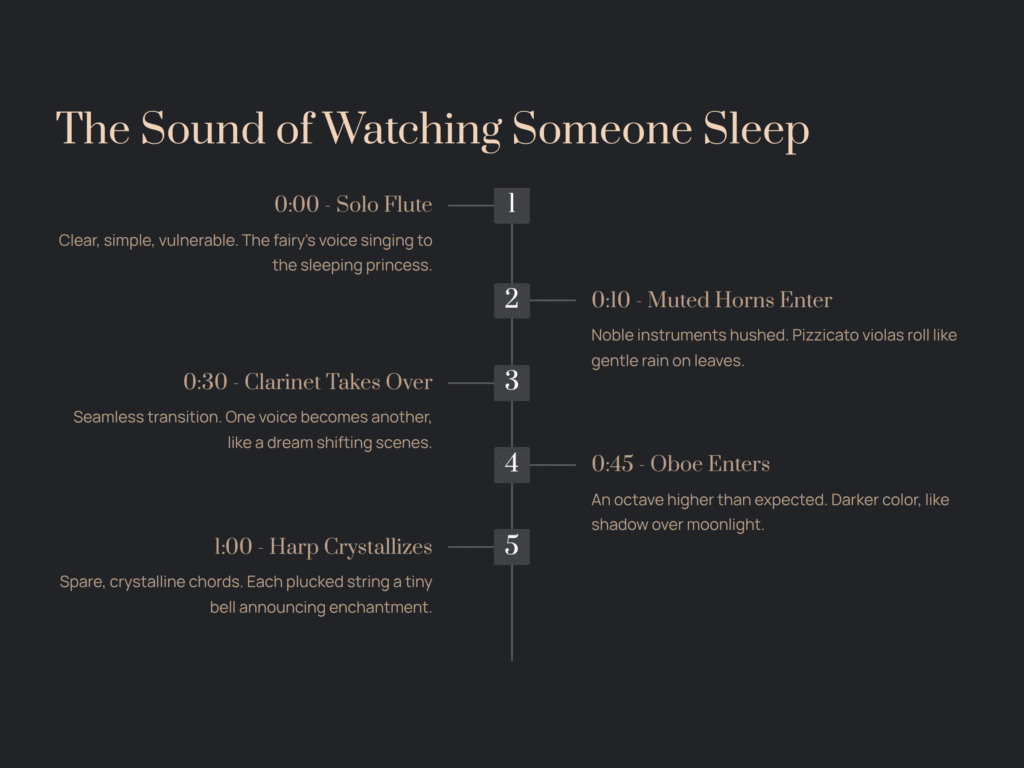

The piece begins with a solo flute—clear, simple, almost naked in its vulnerability. This is the fairy’s voice, or perhaps it’s Mother Goose herself (the old woman who transforms into a fairy in Perrault’s tale), singing to the sleeping princess. The melody is so simple a child could hum it, yet it contains within it something mysteriously adult, something that understands the weight of sleep, of waiting, of time itself.

Then listen—really listen—to what’s happening underneath. Ravel brings in muted horns, those noble instruments suddenly hushed, their usual warmth turned into something more distant, more mysterious. He adds pizzicato strings (that’s when the players pluck instead of bow), but not just any pizzicato. The violas roll across all their strings, creating a texture like gentle rain on leaves, or perhaps the sound of time dripping slowly in an enchanted castle.

About thirty seconds in, the clarinet takes over the melody from the flute. Did you catch that transition? It’s so smooth you might miss it—one voice becomes another, like the way a dream shifts scenes without explaining how you got there. Then the oboe enters, an octave higher than you’d expect (Ravel loved these unusual pairings), adding a slightly darker color, like a shadow passing over moonlight.

The harp enters with spare, crystalline chords. Ravel loved the harp—it appears throughout his work like a signature. Here, each plucked string is a tiny bell announcing… what? A spell deepening? A breath taken? You decide.

What Makes This Two Minutes Different

Here’s what beginners often miss, and what I want you to catch: Ravel doesn’t use any sharp edges in this music. Every possible dissonance—and there are several—is rounded off, softened, made gentle. It’s as if he’s wrapped every harsh sound in silk before letting you hear it.

He also does something extraordinary with musical modes. Instead of a regular minor scale, he uses what’s called the Aeolian mode. Don’t worry about the technical term—what matters is the feeling. The Aeolian mode sounds ancient, like something that existed before major and minor keys were even invented. It makes the music feel timeless, placeless, belonging to the realm of fairy tale rather than any specific country or century.

And those instrument combinations I mentioned? They’re not random. Ravel understood something profound about orchestration: when you combine instruments of wildly different characters—say, a soft flute with muted horns, or high oboes with low cellos—you create a transparency, a clarity where you can hear through the music to all its layers at once. It’s like looking at a stained-glass window where each color is distinct but they all blend into something luminous.

How to Actually Listen to This

I’m going to give you specific instructions, the kind I wish someone had given me years ago.

First listening: Close your eyes. Don’t try to identify instruments or analyze anything. Just let the music wash over you. Notice how you feel. Notice if any images come to mind. For me, it’s always a tower room at twilight, a princess on a bed surrounded by roses, dust motes suspended in a single shaft of light.

Second listening: Follow only the flute. From the very first note to the last time you hear it, track that main melody. It’s the thread that holds everything together. Notice when it passes to the clarinet (around 0:30), then returns (around 1:15). This is your anchor, your guide through the enchanted forest.

Third listening: Now do something unexpected—focus on what’s happening at the very bottom of the music. The cellos and basses, barely audible, are holding everything up like the foundation of a building. They move so slowly you almost don’t notice, but without them, the whole magical structure would collapse.

Fourth listening: This time, listen for the moment when everything comes together—usually around the 1:20 mark. The first violins finally enter, the texture deepens, and for just a few seconds before the piece fades away, you hear the full orchestra breathing as one. Then it dissolves, like morning mist.

The Lesson of Simplicity

What Ravel achieved here isn’t just beautiful music for its own sake. He proved something essential about art: that the most profound emotions don’t require complexity or length or grand gestures. Sometimes all you need is a single flute line, some muted horns, and two minutes of perfect attention to detail.

This is the first movement of a five-movement suite, each one depicting a different fairy tale. But Ravel chose to begin here, with sleep, with stillness, with the moment before the story even starts. It’s a radical choice when you think about it—to open not with action or drama but with its opposite, with the held breath before anything happens.

Perhaps that’s the real magic: teaching us to listen to silence, to stillness, to the space between notes where music becomes something more than sound. In our world of constant noise and movement, two minutes of Ravel’s Pavane is an invitation to remember what it feels like to be fully present, fully quiet, fully enchanted.

The next time you feel overwhelmed, overstimulated, too busy to breathe—find this piece. Put on your headphones. Close your eyes. Let a dead French composer who loved children and fairy tales remind you that the most powerful moments in life, as in music, are often the quietest ones.

That’s what I learned from a sleeping princess and the composer who understood that true sophistication isn’t about showing off what you know—it’s about having the confidence to be simple, clear, and utterly yourself.