📑 Table of Contents

Have you ever watched light dancing on water? That shimmering, ever-shifting quality where nothing stays still, yet everything feels perfectly peaceful? That’s exactly what Claude Debussy captured in his Arabesque No. 1—except he did it with piano keys instead of paint.

In 1888, a 26-year-old Debussy sat down and wrote something that would confuse his professors, enchant audiences, and eventually sell over 100,000 copies during his lifetime. This wasn’t music that told a story or followed the dramatic rules of Beethoven and Brahms. This was music that simply existed, like morning mist or the curves of a vine climbing a garden wall.

Let’s explore why this five-minute piece continues to mesmerize listeners over 130 years later.

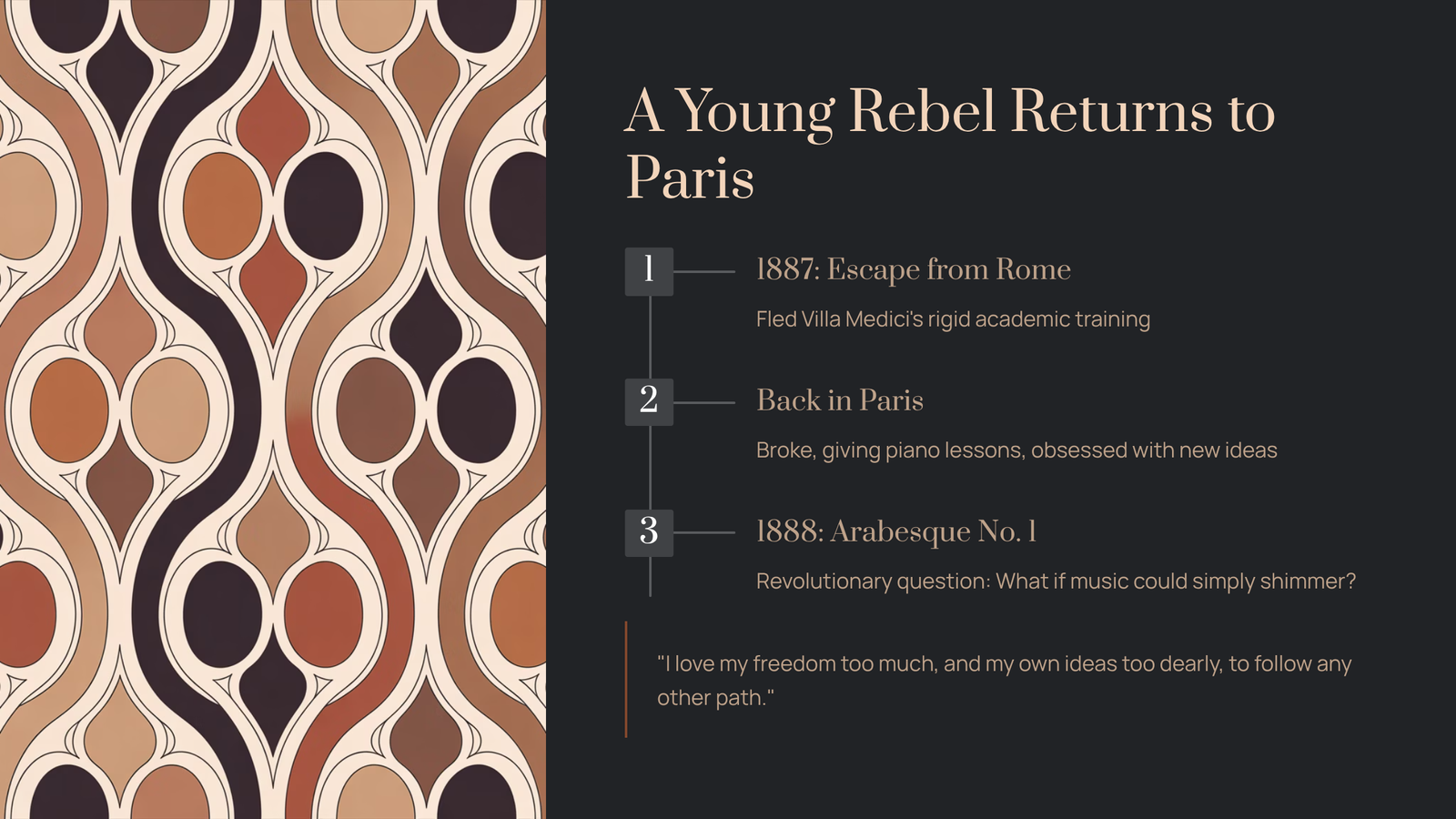

A Young Rebel Returns to Paris

To understand Arabesque No. 1, you need to know what Debussy was running away from.

Just a year before composing this piece, Debussy had escaped from Rome’s Villa Medici, where France’s most promising young composers were supposed to study. He hated it. The rigid academic training felt suffocating to someone who later wrote: “I love my freedom too much, and my own ideas too dearly, to follow any other path.”

Back in Paris at 26, Debussy was broke, giving piano lessons to survive, and completely obsessed with a new question: What if music didn’t have to go anywhere? What if it could simply shimmer and exist, like the decorative patterns he saw in Art Nouveau posters and arabesque designs from the Middle East?

The title itself reveals his intention. An “arabesque” refers to those intricate, flowing decorative patterns found in Islamic art—lines that curve and interweave without beginning or end. Debussy wanted to translate that visual concept into sound.

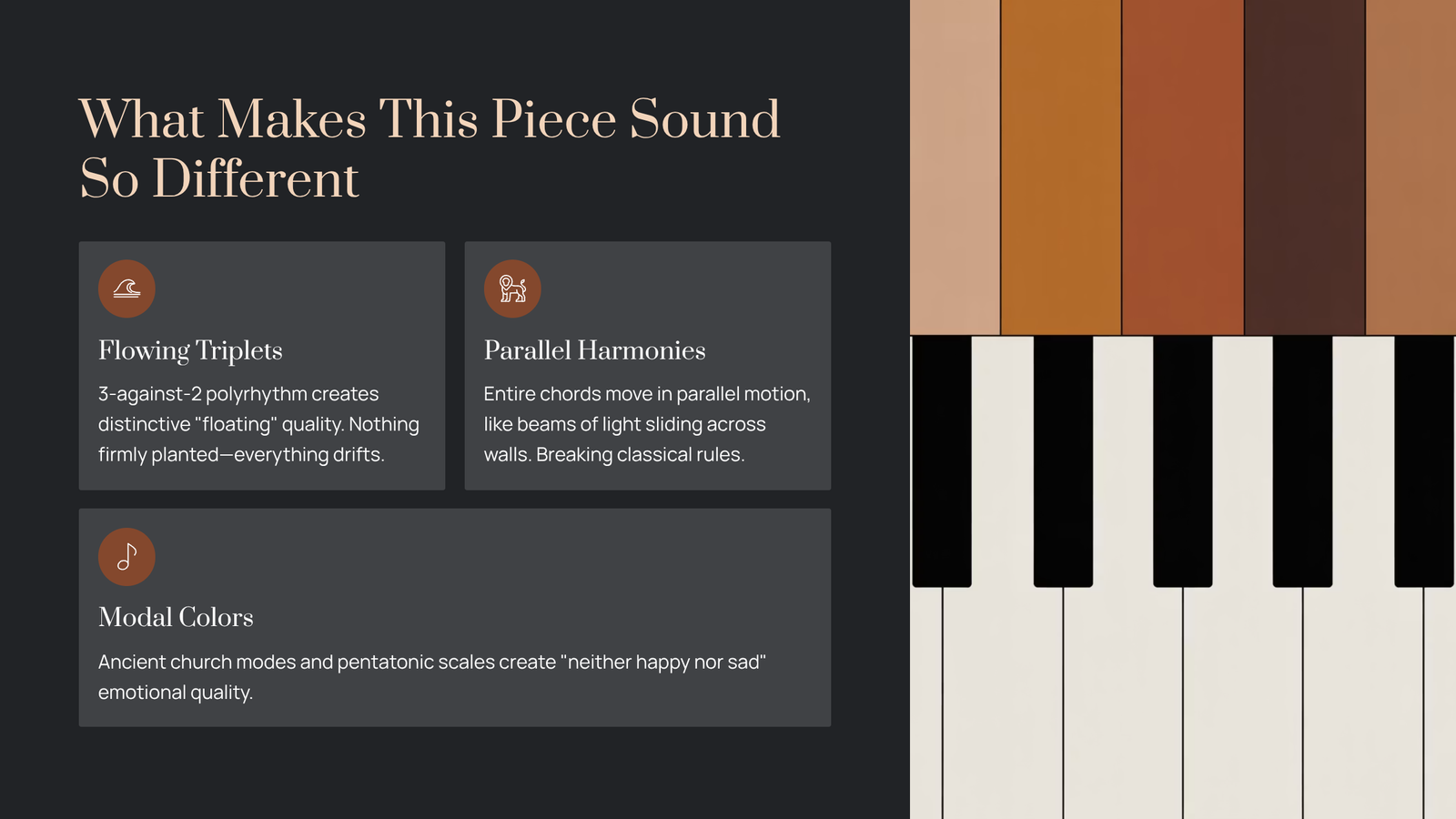

What Makes This Piece Sound So Different

If you’ve ever wondered why Arabesque No. 1 sounds unlike anything from Mozart or Chopin, here’s the secret: Debussy was deliberately breaking the rules his teachers had drilled into him.

The Flowing Triplets

From the very first measure, your ear catches something unusual. The right hand plays constant triplets—three notes per beat—while the left hand plays regular eighth notes, two per beat. This creates a 3-against-2 polyrhythm that gives the music its distinctive “floating” quality. Nothing feels firmly planted on the ground. Everything drifts.

Parallel Harmonies

Classical harmony has strict rules about how chords should move. Debussy ignored them. He moved entire chords in parallel motion, like beams of light sliding across a wall. His contemporaries thought this was lazy or incorrect. Debussy thought it was beautiful.

Modal Colors

Instead of staying locked into major and minor keys, Debussy borrowed from ancient church modes and pentatonic scales (the five-note scales you hear in East Asian music). This gives Arabesque No. 1 its “neither happy nor sad” emotional quality—more like contentment or gentle wonder.

A Listening Guide: Following the Journey

The piece unfolds in a simple three-part structure (A-B-A), but within that framework, Debussy creates a remarkable emotional journey.

Opening Section (0:00–2:00)

The music begins with transparent, crystalline chords floating down from high on the keyboard. Listen for how the melody seems hidden within the triplet patterns—the notes A, G-sharp, F-sharp, and E form a descending line that your ear catches almost subconsciously. The dynamic stays soft, barely above a whisper. Imagine watching clouds drift across a pale morning sky.

Middle Section (2:00–3:30)

Here the character shifts. The tempo picks up slightly, and there’s more warmth in the sound. One Debussy scholar described this section as “humming a little tune to yourself during a walk on a sunny spring day.” The music modulates to A major, then makes a bold leap to C major, adding brightness and gentle joy. Watch for two brief climaxes around the 2:30 mark—sudden swells to forte before immediately retreating to piano.

Return and Climax (3:30–end)

The original theme returns in E major, but now something remarkable happens. Around the 4:00 mark, Debussy places the piece’s emotional climax—except it’s quiet. This is the paradox at the heart of Arabesque No. 1: its moment of deepest feeling comes in a hushed whisper, not a triumphant roar. Two melodic voices appear in the right hand, singing a gentle duet before merging together. The piece dissolves into silence like morning dew evaporating.

Recommended Recordings to Start With

Different pianists bring vastly different personalities to this music, and exploring multiple interpretations can deepen your appreciation.

For Pure Beauty: Claudio Arrau

The Chilean master’s recording captures the music’s transparency and gentle warmth. His touch is singing and luminous, letting each voice breathe independently.

For Structural Clarity: Walter Gieseking

The German pianist who essentially defined how we hear Debussy. His interpretation emphasizes the architecture beneath the shimmering surface, with pristine fingerwork and subtle pedaling.

For Character and Surprise: Marguerite Long

A French pianist who studied with the composers who knew Debussy personally. Her version is more direct, almost brusque compared to dreamier interpretations—a bracing alternative that reveals the music’s wit alongside its beauty.

For Something Completely Different: Isao Tomita (Synthesizer)

The Japanese electronic musician created a synthesizer arrangement that became famous as the theme music for the American TV show “Star Gazers” from 1976 to 2011. It’s a fascinating reimagining that proves how adaptable Debussy’s vision can be.

Why This Piece Matters

Arabesque No. 1 represents a turning point in Western music. Before Debussy, most classical compositions were about development—taking a theme and transforming it through conflict and resolution, like a novel with rising action and climax.

Debussy suggested another possibility: music as atmosphere, as texture, as pure sensory experience. He wasn’t telling you a story. He was inviting you to exist inside a particular quality of light and air.

This idea would influence nearly everything that came after—from Ravel to ambient music to film scores to lo-fi beats for studying. Every time you hear music designed to create a mood rather than narrate a drama, you’re hearing Debussy’s legacy.

The remarkable thing is that Debussy achieved all this while still writing music that feels effortless and natural. There’s no showing off, no technical pyrotechnics. Just five minutes of sound that somehow makes the world seem a little more beautiful than it was before.

Tips for First-Time Listeners

If you’re new to classical music, here are some ways to approach this piece:

First Listen: Just Float

Don’t try to analyze anything. Put on headphones, close your eyes, and let the music wash over you. Notice what images or feelings arise naturally.

Second Listen: Follow the Dynamics

Pay attention to the volume changes. Notice how Debussy uses mostly quiet dynamics, making the few louder moments feel significant.

Third Listen: Catch the Hidden Melody

In the opening section, try to hear the descending melody (A-G#-F#-E) hidden within the triplet figures. Once you catch it, you’ll hear the music differently forever.

Bonus: Try Different Times of Day

This piece transforms depending on when you hear it. Early morning, late at night, during a rainstorm—each context reveals different qualities in the music.

Whatever brings you to Arabesque No. 1—whether you’re seeking focus music for work, a moment of calm in a chaotic day, or your first steps into classical piano—you’re encountering one of those rare pieces that seems to exist outside of time. Debussy wrote it 137 years ago, but it sounds like it could have been composed yesterday, or a thousand years from now.

That’s the magic of a 26-year-old rebel who decided that music didn’t have to follow anyone’s rules but its own.